Everything you need for everything you read.

Use our guides to learn or teach any of the 3056 titles and topics we cover.

Browse Our Guides

Recently added

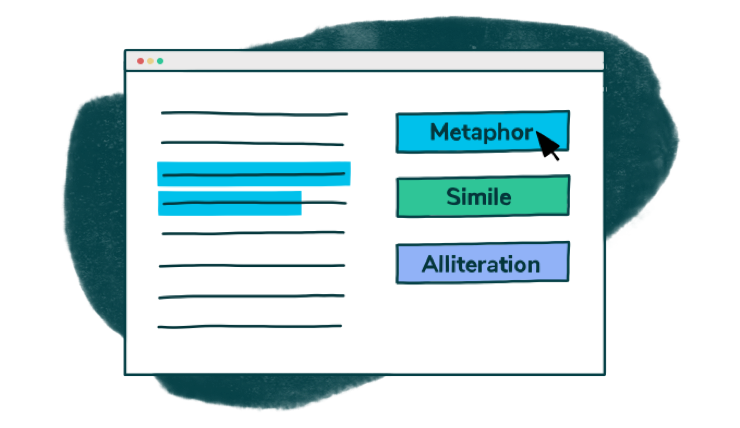

Literature, Explained Better

A more helpful approach

Our guides use color and the interactivity of the web to make it easier to learn and teach literature.

Every title you need

Far beyond just the classics, LitCharts covers over 2000 texts read and studied worldwide, from Judy Blume to Nietzsche.

For every reader

Our approach makes literature accessible to everyone, from students at every level to teachers and book club readers.

More than

50 million

students, teachers,

parents, and readers use LitCharts.

parents, and readers use LitCharts.

1912

Literature guides

967

Poetry guides

136

Terms & devices guides

All 41

Shakespeare translations

Get LitCharts

Join over 150,000 LitCharts readers who have upgraded

and get unlimited access to all content including: