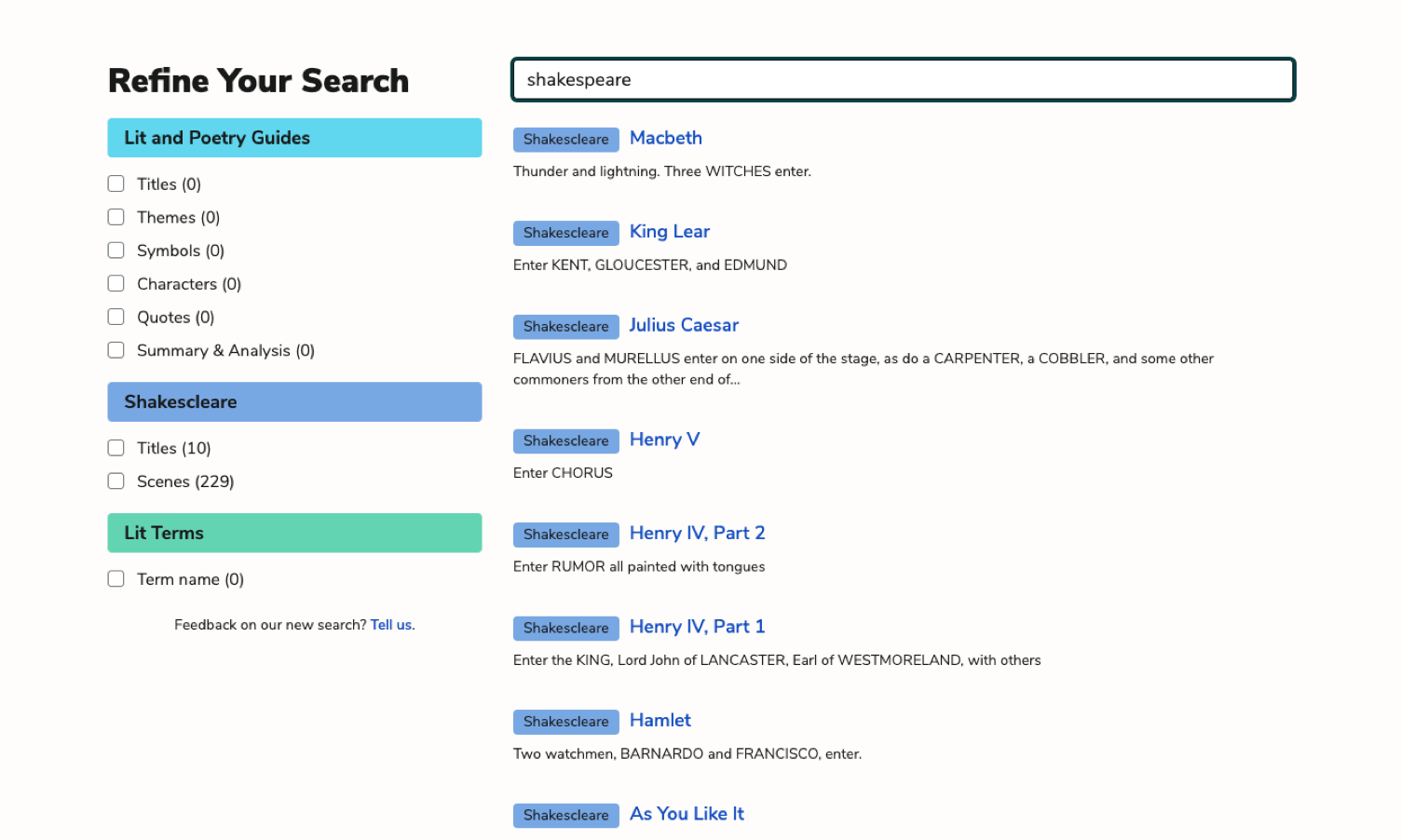

- All's Well That Ends Well

- Antony and Cleopatra

- As You Like It

- The Comedy of Errors

- Coriolanus

- Cymbeline

- Hamlet

- Henry IV, Part 1

- Henry IV, Part 2

- Henry V

- Henry VI, Part 1

- Henry VI, Part 2

- Henry VI, Part 3

- Henry VIII

- Julius Caesar

- King John

- King Lear

- Love's Labor's Lost

- A Lover's Complaint

- Macbeth

- Measure for Measure

- The Merchant of Venice

- The Merry Wives of Windsor

- A Midsummer Night's Dream

- Much Ado About Nothing

- Othello

- Pericles

- The Rape of Lucrece

- Richard II

- Richard III

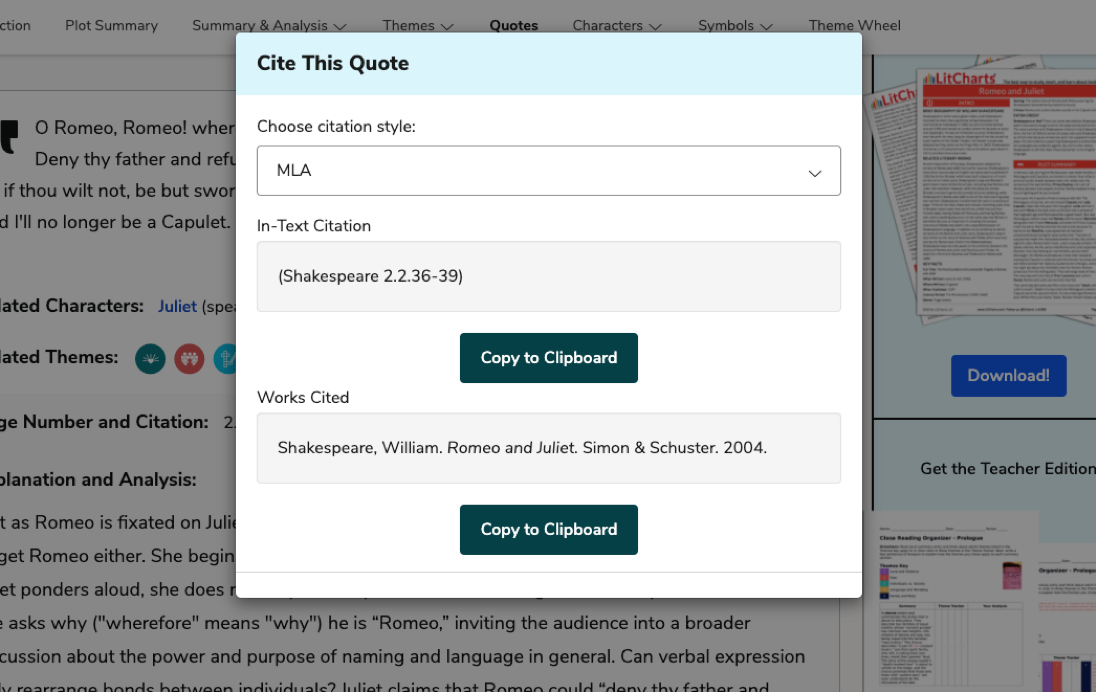

- Romeo and Juliet

- Shakespeare's Sonnets

- The Taming of the Shrew

- The Tempest

- Timon of Athens

- Titus Andronicus

- Troilus and Cressida

- Twelfth Night

- The Two Gentlemen of Verona

- Venus and Adonis

- The Winter's Tale

As Lewis comes to end of the first part of his book, he’s reached some important conclusions about God. He’s shown that God is an all-powerful, deeply moral being: he creates a code of Right and Wrong that all human beings instinctively follow (or feel guilty about breaking). And yet Lewis ends Book One explaining that it is impossible to become a Christian simply in order to reap God’s rewards. It’s surprising that Lewis makes this point, since Christianity often seems to advertise Heaven and salvation as rewards for belief in God and Christ (as it says in the New…