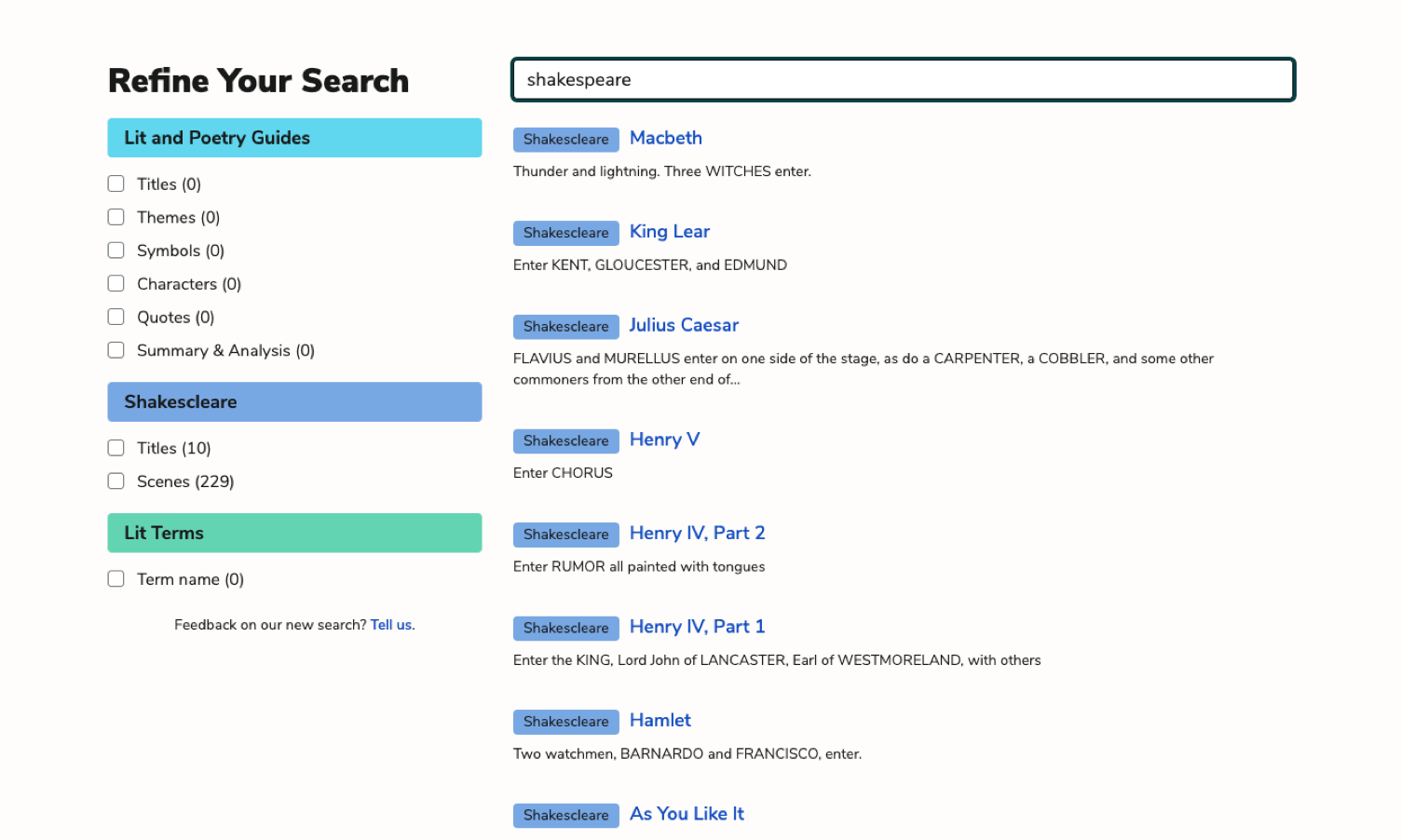

- All's Well That Ends Well

- Antony and Cleopatra

- As You Like It

- The Comedy of Errors

- Coriolanus

- Cymbeline

- Hamlet

- Henry IV, Part 1

- Henry IV, Part 2

- Henry V

- Henry VI, Part 1

- Henry VI, Part 2

- Henry VI, Part 3

- Henry VIII

- Julius Caesar

- King John

- King Lear

- Love's Labor's Lost

- A Lover's Complaint

- Macbeth

- Measure for Measure

- The Merchant of Venice

- The Merry Wives of Windsor

- A Midsummer Night's Dream

- Much Ado About Nothing

- Othello

- Pericles

- The Rape of Lucrece

- Richard II

- Richard III

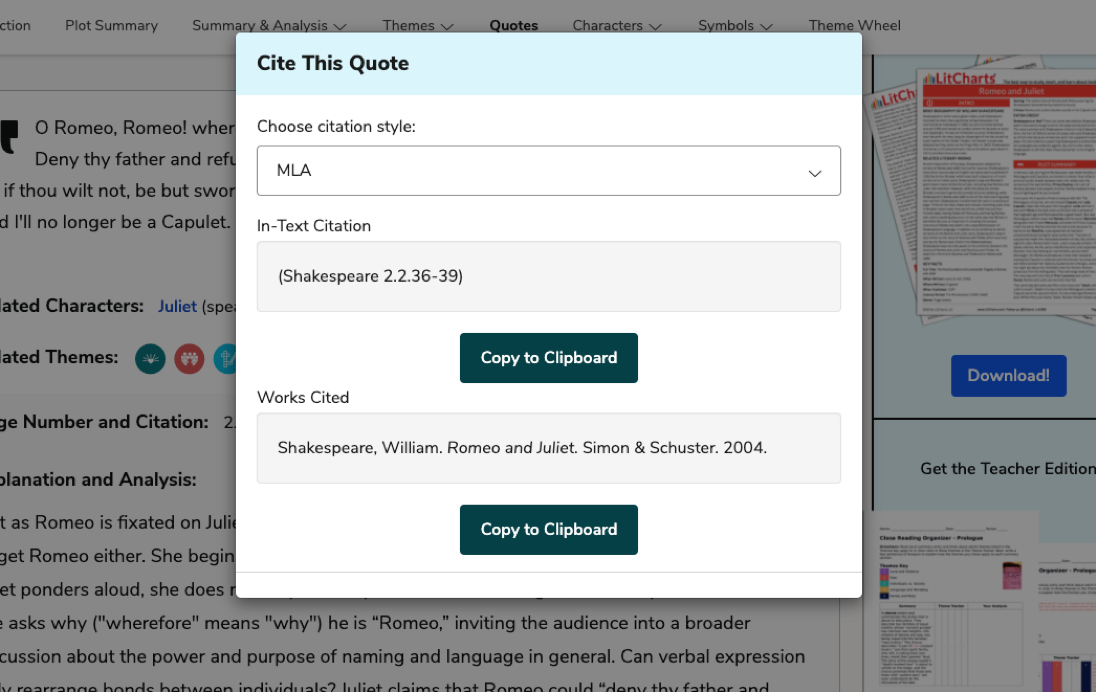

- Romeo and Juliet

- Shakespeare's Sonnets

- The Taming of the Shrew

- The Tempest

- Timon of Athens

- Titus Andronicus

- Troilus and Cressida

- Twelfth Night

- The Two Gentlemen of Verona

- Venus and Adonis

- The Winter's Tale

Baldwin writes this to James in reference to his own father, who was the boy’s grandfather, though James never met him. Baldwin states in a rather blunt manner that his father had “a terrible life,” which suggests that he is not particularly sentimental about his father’s death. In this way, it becomes clear that, more than eulogizing his father, Baldwin wants to use him as an example; he wants to teach James using the mistakes his father made, the most damning of which was his tendency to believe the detrimental things white people said about him.

Baldwin believes that his…