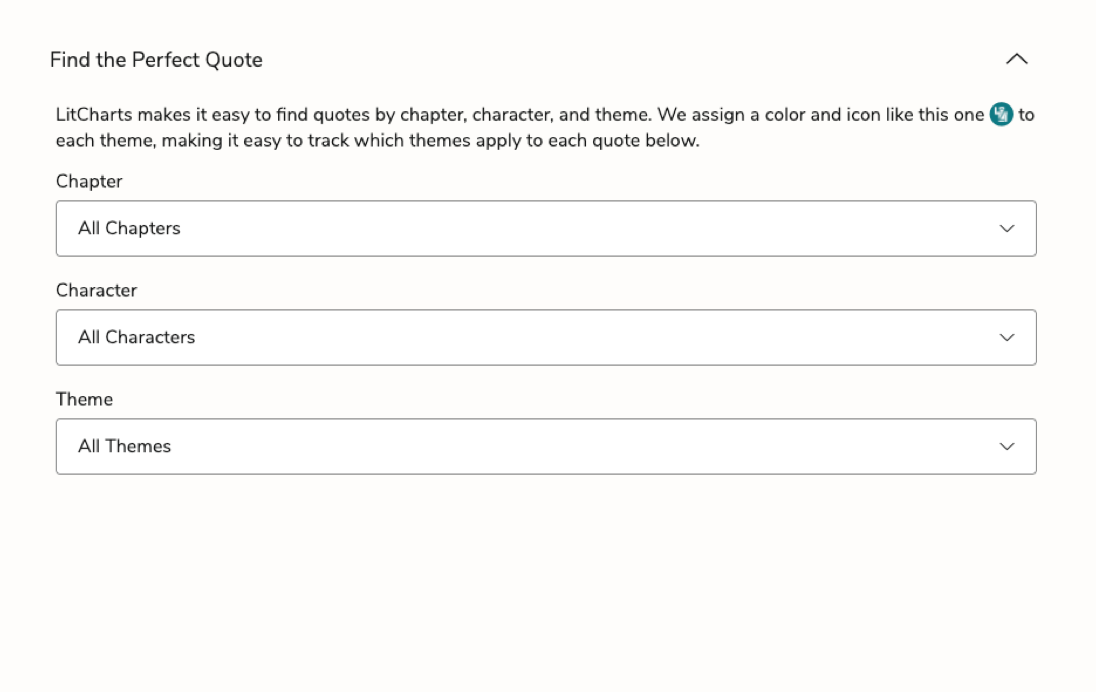

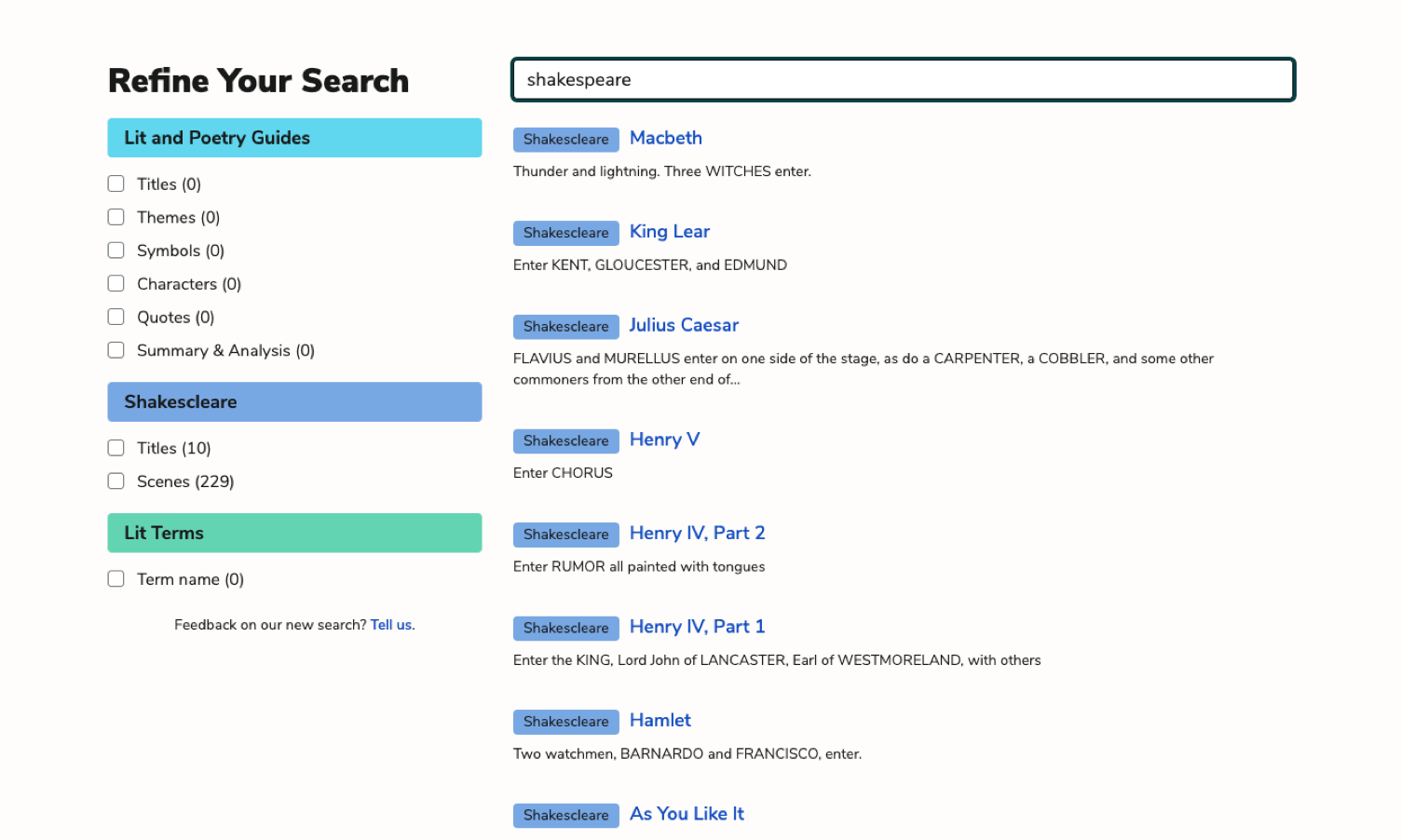

- All's Well That Ends Well

- Antony and Cleopatra

- As You Like It

- The Comedy of Errors

- Coriolanus

- Cymbeline

- Hamlet

- Henry IV, Part 1

- Henry IV, Part 2

- Henry V

- Henry VI, Part 1

- Henry VI, Part 2

- Henry VI, Part 3

- Henry VIII

- Julius Caesar

- King John

- King Lear

- Love's Labor's Lost

- A Lover's Complaint

- Macbeth

- Measure for Measure

- The Merchant of Venice

- The Merry Wives of Windsor

- A Midsummer Night's Dream

- Much Ado About Nothing

- Othello

- Pericles

- The Rape of Lucrece

- Richard II

- Richard III

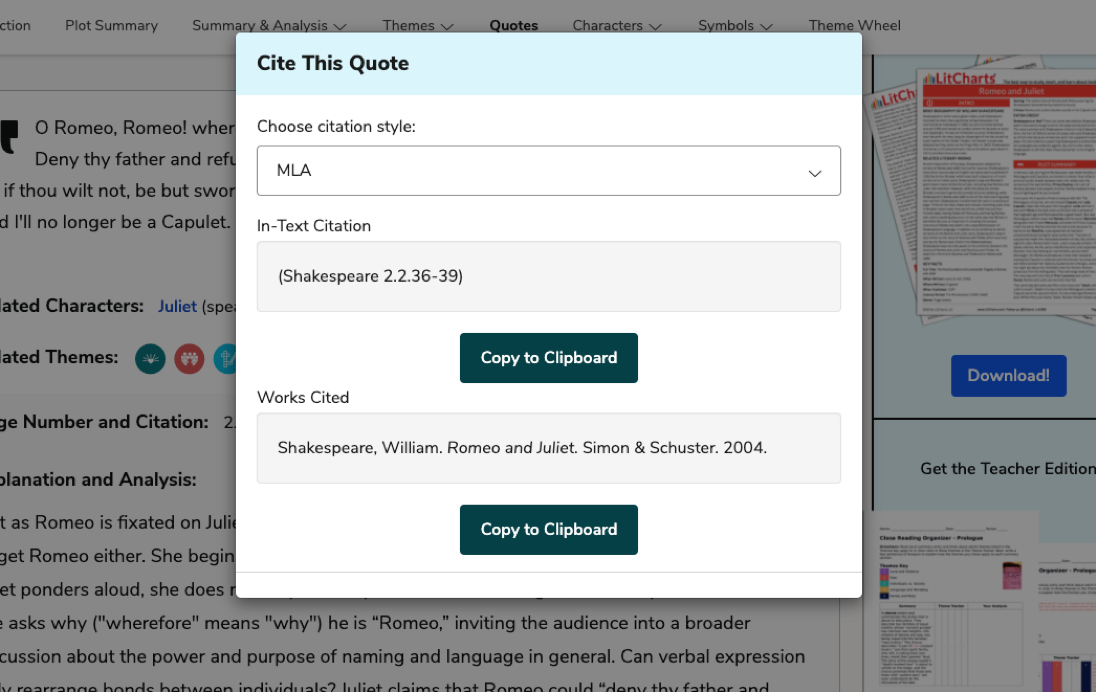

- Romeo and Juliet

- Shakespeare's Sonnets

- The Taming of the Shrew

- The Tempest

- Timon of Athens

- Titus Andronicus

- Troilus and Cressida

- Twelfth Night

- The Two Gentlemen of Verona

- Venus and Adonis

- The Winter's Tale

The end of “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” contains its most shocking, ambiguous scene. Hemingway does not reveal whether Margot purposefully shot her husband—noting instead that she “shot at the buffalo,” hitting Macomber on his skull—leaving it up to readers to decide whether Margot is a murderess or just a bad shooter. By affording the reader multiple paths of interpretations for Macomber’s death, Hemingway points to the complicated, ambivalent nature of relationships between men and women. Did Margot wish to reclaim the power that Macomber took away from her by becoming a “man of action?” Did Margot want…