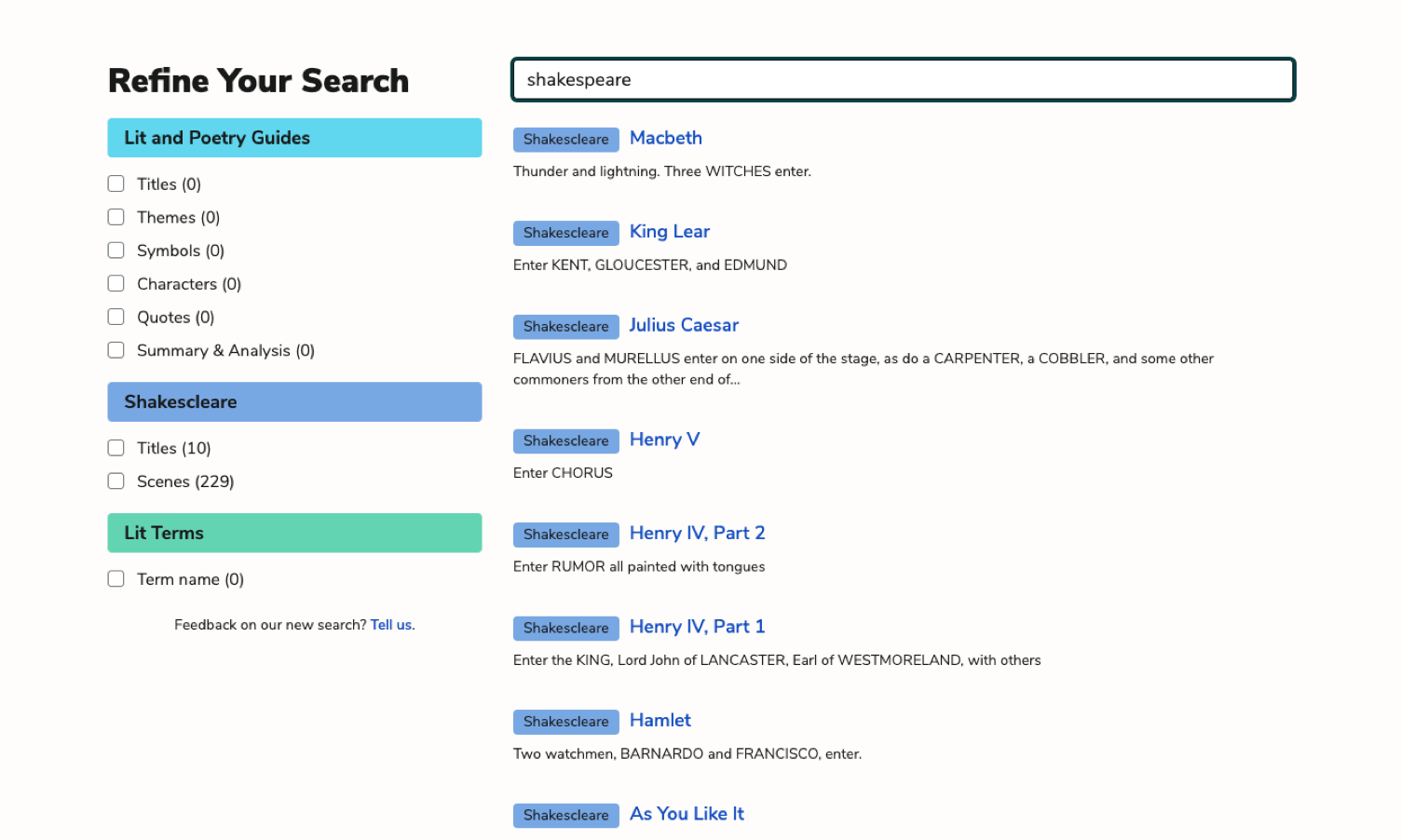

- All's Well That Ends Well

- Antony and Cleopatra

- As You Like It

- The Comedy of Errors

- Coriolanus

- Cymbeline

- Hamlet

- Henry IV, Part 1

- Henry IV, Part 2

- Henry V

- Henry VI, Part 1

- Henry VI, Part 2

- Henry VI, Part 3

- Henry VIII

- Julius Caesar

- King John

- King Lear

- Love's Labor's Lost

- A Lover's Complaint

- Macbeth

- Measure for Measure

- The Merchant of Venice

- The Merry Wives of Windsor

- A Midsummer Night's Dream

- Much Ado About Nothing

- Othello

- Pericles

- The Rape of Lucrece

- Richard II

- Richard III

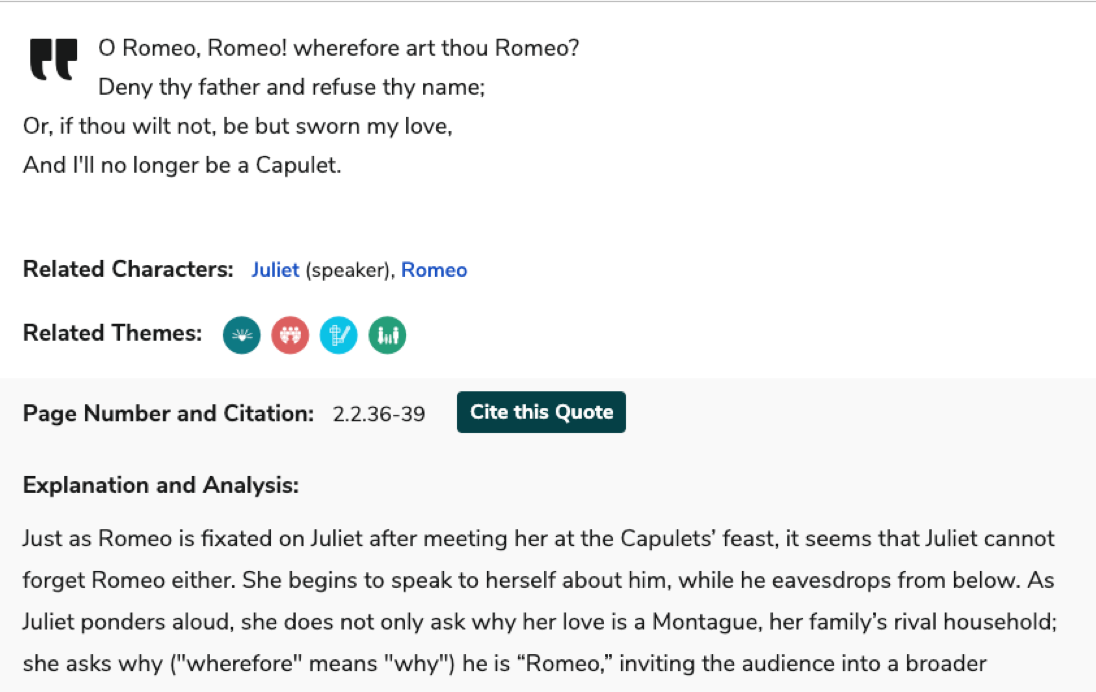

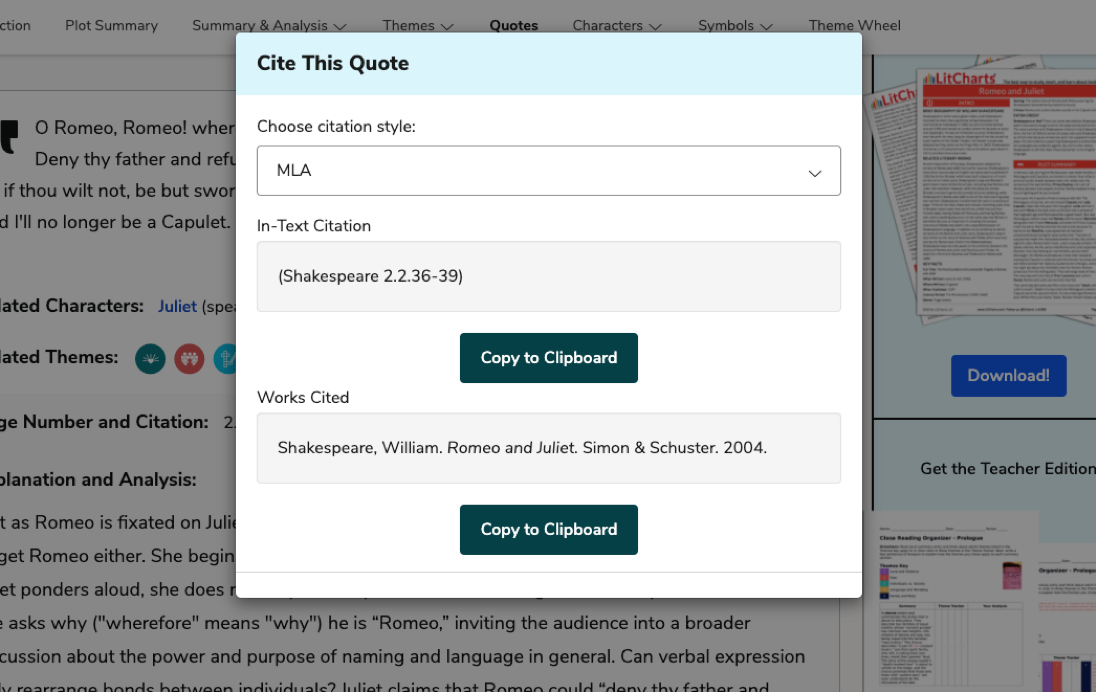

- Romeo and Juliet

- Shakespeare's Sonnets

- The Taming of the Shrew

- The Tempest

- Timon of Athens

- Titus Andronicus

- Troilus and Cressida

- Twelfth Night

- The Two Gentlemen of Verona

- Venus and Adonis

- The Winter's Tale

This occurred when Fadiman accompanied Martin Kilgore to the Lees’ house to watch him perform a routine at-home checkup after Lia’s final neurological crisis. Although it may seem harmless and small, Martin’s admonition of Lia’s sister—“Don’t do that, there’s a good boy”—is fraught with significance. Beyond the obvious fact that he misidentified the child’s gender (lending a certain out-of-touch quality to this interaction), he risked overstepping familial hierarchies of which he was most likely unaware. By telling Nao Kao and Foua’s child not to do something, he intensified the powerful role he already occupied by virtue of his position as…