|

|

Have questions?

Contact us

Already a member? Sign in

|

Get every literary device explanation for Oliver TwistPlus so much more...

Sign up for LitCharts A+Get instant access to every literary device explanation, plus so much more...

Foil

Explanation and Analysis—Fagin and Sikes:

Fagin and Sikes, two of the novel's villains, are foils for one another. It becomes clearest that they represent two sides of the same coin (criminality) in chapter 52, when Mr. Brownlow justifies taking young Oliver to see Fagin in prison:

[M]y business with this man is intimately connected with him, and as this child has seen him in the full career of his success and villany, I think it better—even at the cost of some pain and fear—that he should see him now.

It is important to Mr. Brownlow that Oliver witness prison, and the horrifying scaffold that awaits Fagin outside it, as the natural end a criminal is supposed to meet at the hands of the government. Mr. Brownlow takes responsibility at the end of the book for Oliver's moral education and for fully extracting him from the immoral life of crime he almost fell into when he was "intimately connected" with Fagin. Fagin has been figured throughout the novel in dehumanizing, anti-Semitic language. His inhumanity and lack of qualms about mistreating others have made him a highly successful villain up to the point of his capture, suggesting that inhumanity and criminality go hand-in-hand. Through watching Fagin come to his violent end, Brownlow thinks Oliver will understand the full arc of the inhuman, morally bankrupt criminal, who must eventually meet with prison and capital punishment. As a visitor to the prison instead of an inmate, Oliver is cemented in his position as a moral, law-abiding citizen who belongs to the free world.

But Sikes, Fagin's one-time henchman, complicates the simple narrative of evil criminal vs. virtuous citizen that Brownlow is trying to construct for Oliver. Ultimately, Sikes's crimes land him in a similar place as Fagin: death by hanging. This death reinforces the idea that criminals tend to die for their crimes eventually. Sikes, though, cannot be said to be quite as inhuman as Fagin. It is Sikes's own guilty conscience, rather than the state, that punishes him for murdering Nancy. This is not an intentional suicide, which Dickens's Victorian readers might have taken as further evidence of Sikes's immorality. Rather, Sikes accidentally hangs himself when he fumbles with a rope because he can't stop imagining that his dog is chasing him and holding him accountable for murder. Fagin, on the other hand, never has such a guilty conscience.

Even Sikes's murder of Nancy is more emotional than any of Fagin's crimes, which (true to Fagin's anti-Semitic depiction) are all premeditated and calculated for financial gain. Sikes murders Nancy in a spontaneous fit of jealous rage into which Fagin has manipulated him. The fact that Sikes is an emotional murderer and dies because he is emotional about what he has done does not excuse his actions, but it does contrast Fagin's straightforward villainy. Through the contrast between these two criminal types, Dickens preserves the idea that criminality might be easier for people to stumble into than Mr. Brownlow and many of Dickens's wealthy readers might like to believe.

Monthly

Annual (Best Value)

$595USD/mo

Charged $71.40 USD every year

Teacher

Teacher$795USD/mo

Charged $95.40 USD every year

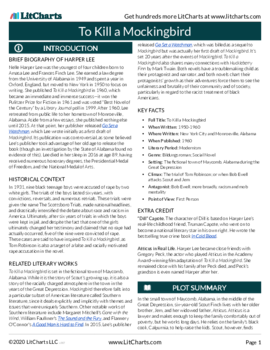

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Instant PDF downloads of all 2238 LitCharts literature guides and of every new one we publish. Try a free sample literature guide.

"Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!"

Quotes Explanations

Find the perfect quote. Understand it perfectly. Then rock the citation, too.

For all 49,909 quotes we cover.

For all 49,909 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

Close reading made easy for students.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

Literary Terms and Devices

Definitions and examples for every literary term and device you need to know.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Try a free sample literary term PDF.

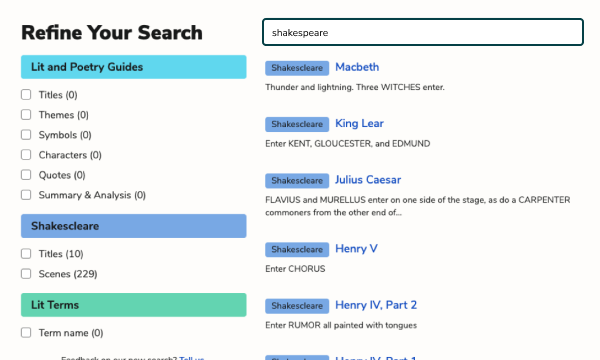

Advanced Search

Refine any search. Find related themes, quotes, symbols, characters, and more.

Poetry Guides

Line-by-line explanations and analysis of figurative language and poetic devices.

For every lyric poem we cover.

For every lyric poem we cover.