|

|

Have questions?

Contact us

Already a member? Sign in

|

Get every literary device explanation for The Ones Who Walk Away from OmelasPlus so much more...

Sign up for LitCharts A+Get instant access to every literary device explanation, plus so much more...

Imagery

Explanation and Analysis—White-Gold Fire:

As she sets the scene for the rest of the tale, the author uses visual imagery to emphasize the pristine, mythical quality of the landscape around Omelas. Everything about the city is bright and beautiful, from the “air of morning” its citizens breathe to the distant mountains on the horizon:

The air of morning was so clear that the snow still crowning the Eighteen Peaks burned with white-gold fire across the miles of sunlit air, under the dark blue of the sky.

The visual imagery here gives the reader an impression of Omelas as an enchantingly clean and crisp city. It’s a true utopia, almost supernaturally untouched by grime, crime, or the mess of everyday life. Elements of natural beauty that seem to defy physics can co-exist here: it’s the time of the Summer Festival, but there’s still visible snow on the mountains in the distance. This description of the "snow still crowning the Eighteen Peaks" that "burned with white-gold fire" is like a Renaissance painting, conjuring conventional imagery of white and gold, purity and power. This vision of pure snow and golden sunshine under the "dark blue of the sky" is also a striking visual contrast, painting a bold picture for the reader. They are charmed by the beauty and drawn into the fairy-tale setting, which sets the stage for the ethical dilemma at the center of the story. Were Omelas less beautiful and perfect, it would be even more difficult to justify the suffering of the scapegoat child. These descriptions also make the "darkness" outside the city seem even more foreboding.

Monthly

Annual (Best Value)

$595USD/mo

Charged $71.40 USD every year

Teacher

Teacher$795USD/mo

Charged $95.40 USD every year

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Instant PDF downloads of all 2238 LitCharts literature guides and of every new one we publish. Try a free sample literature guide.

"Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!"

Quotes Explanations

Find the perfect quote. Understand it perfectly. Then rock the citation, too.

For all 49,919 quotes we cover.

For all 49,919 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

Close reading made easy for students.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

Literary Terms and Devices

Definitions and examples for every literary term and device you need to know.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Try a free sample literary term PDF.

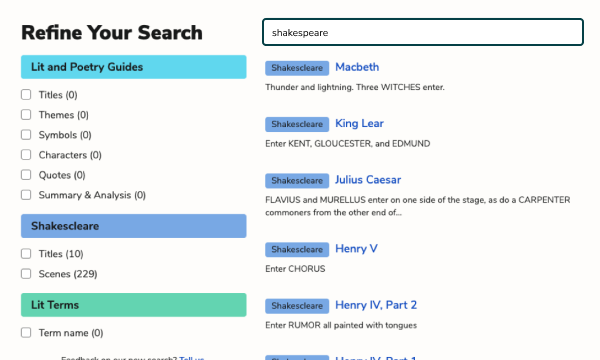

Advanced Search

Refine any search. Find related themes, quotes, symbols, characters, and more.

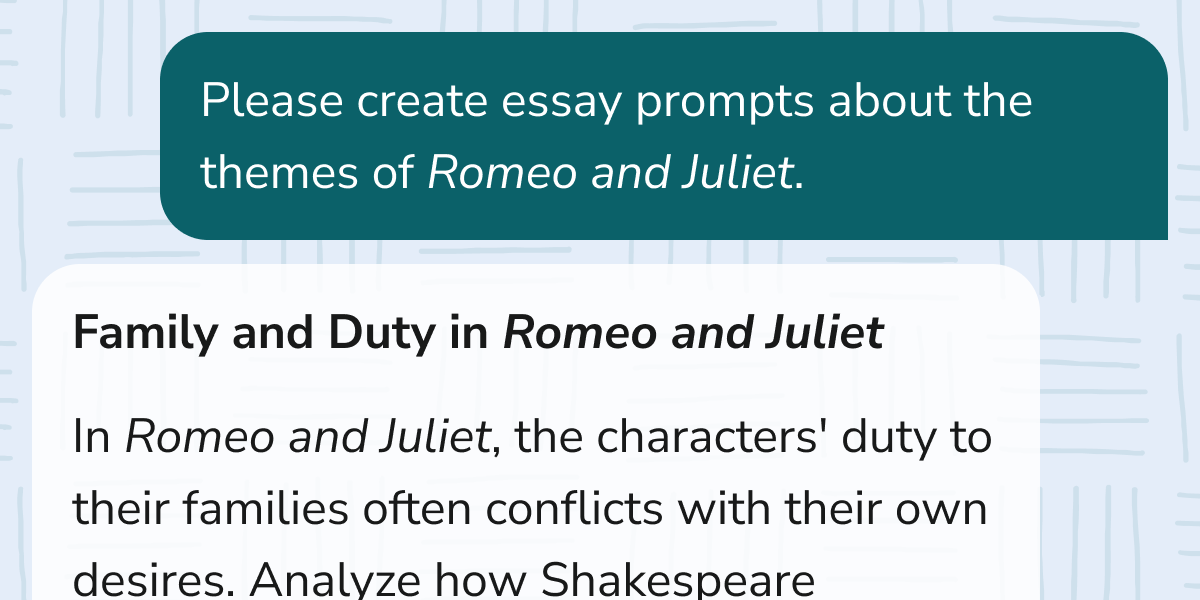

Poetry Guides

Line-by-line explanations and analysis of figurative language and poetic devices.

For every lyric poem we cover.

For every lyric poem we cover.