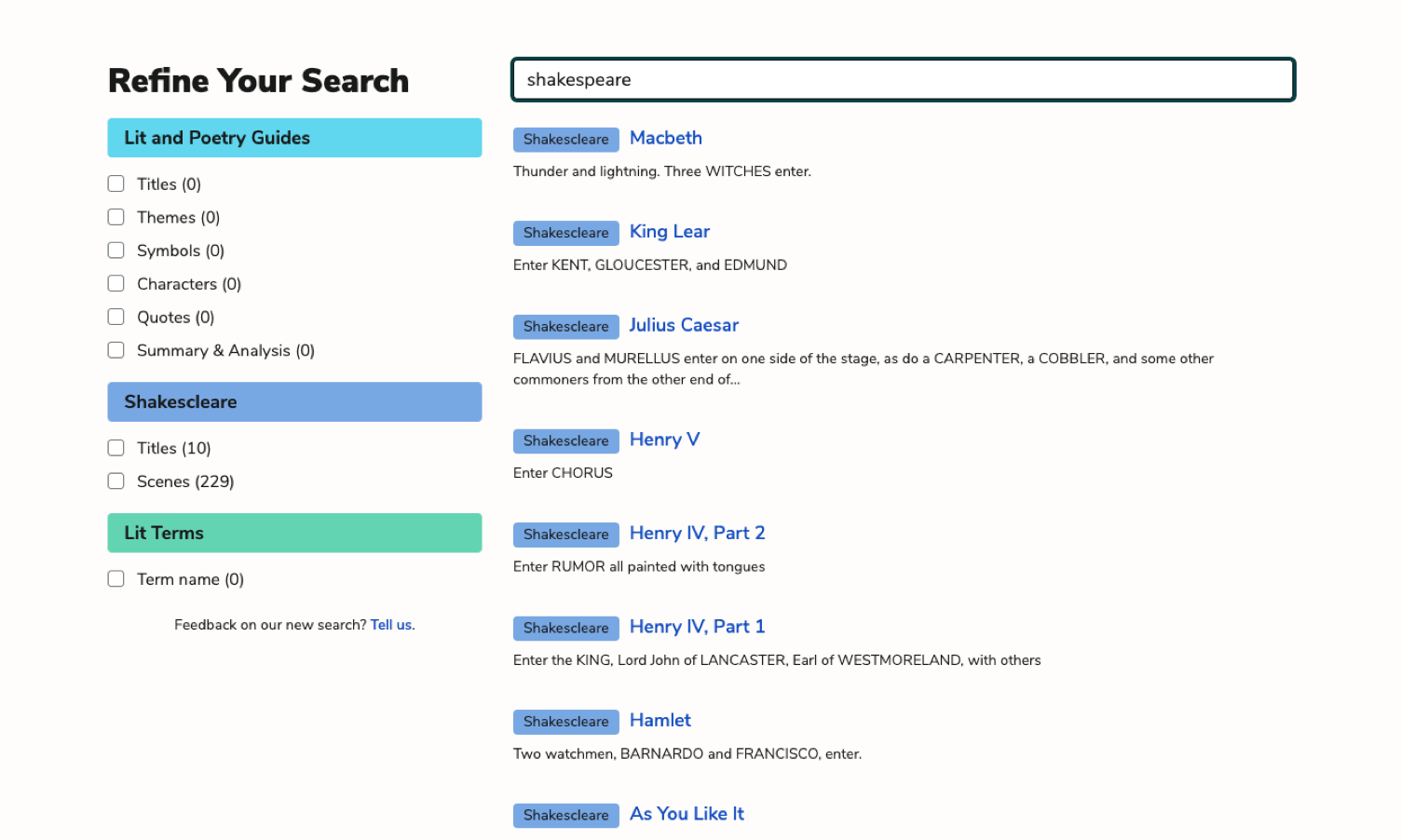

- All's Well That Ends Well

- Antony and Cleopatra

- As You Like It

- The Comedy of Errors

- Coriolanus

- Cymbeline

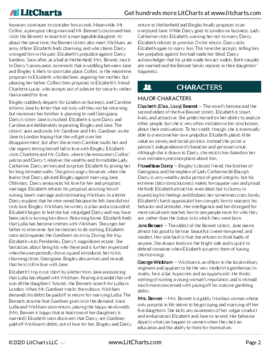

- Hamlet

- Henry IV, Part 1

- Henry IV, Part 2

- Henry V

- Henry VI, Part 1

- Henry VI, Part 2

- Henry VI, Part 3

- Henry VIII

- Julius Caesar

- King John

- King Lear

- Love's Labor's Lost

- A Lover's Complaint

- Macbeth

- Measure for Measure

- The Merchant of Venice

- The Merry Wives of Windsor

- A Midsummer Night's Dream

- Much Ado About Nothing

- Othello

- Pericles

- The Rape of Lucrece

- Richard II

- Richard III

- Romeo and Juliet

- Shakespeare's Sonnets

- The Taming of the Shrew

- The Tempest

- Timon of Athens

- Titus Andronicus

- Troilus and Cressida

- Twelfth Night

- The Two Gentlemen of Verona

- Venus and Adonis

- The Winter's Tale

plus so much more...

-

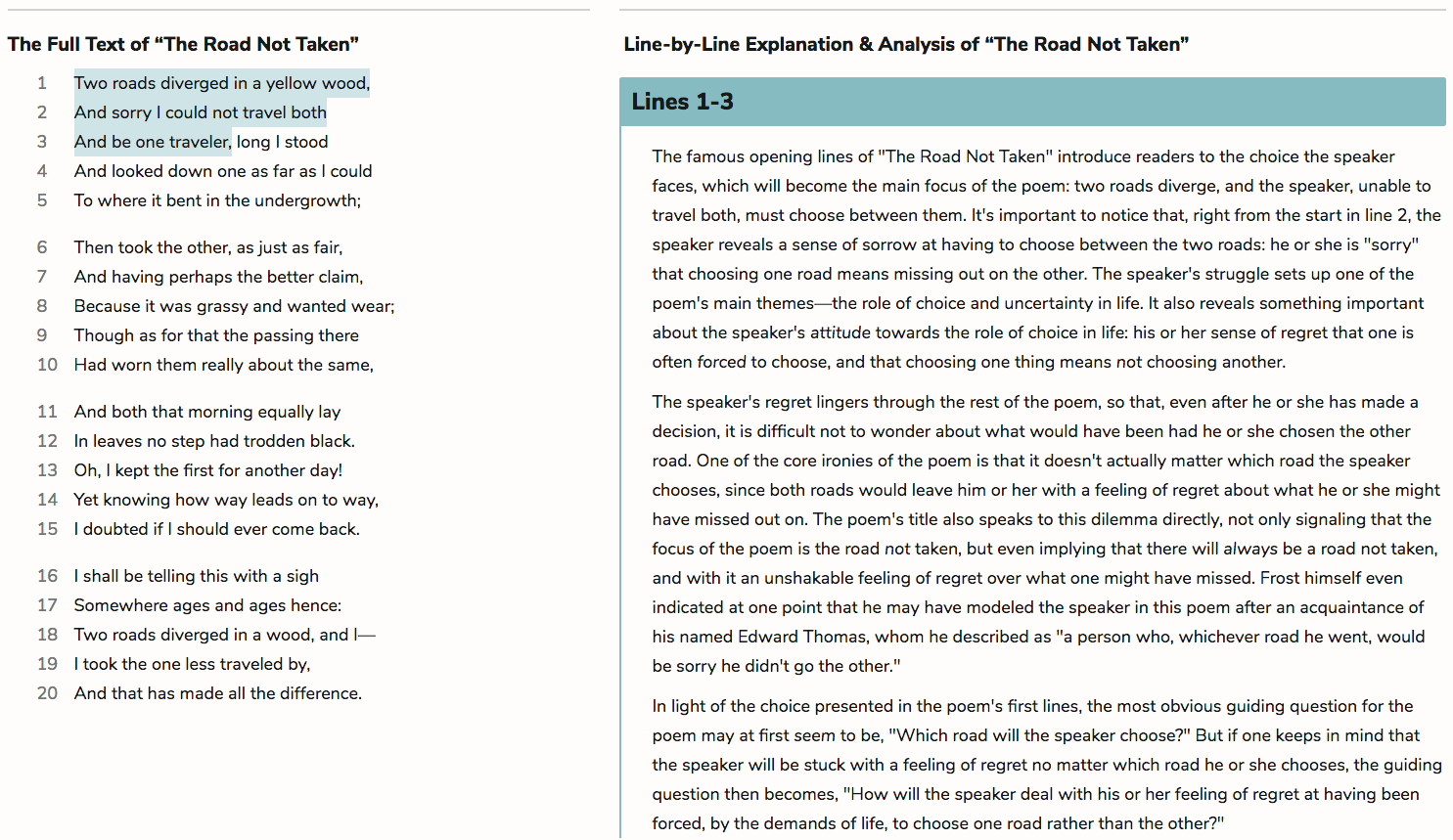

Lines 1-4

"The Trees are Down" opens with a quote from the Book of Revelation, in which an unnamed figure calls out a command not to hurt the earth, sea, or trees. This passage's broader biblical context is explored in the Vocabulary & References section. But even without background information, the quote provides some insight into the coming poem's themes, namely humankind's destruction of nature and the connectedness of all living things.

The first line of the poem itself makes a very plain statement that an unidentified group of people is cutting down trees in a garden. In contrast to the remainder of the poem, line 1 does not contain an end rhyme. (Even the last word of line 3 rhymes with the poem's title and epigraph.) It also does not contain the caesurae that will come to define the poem's structure. As a result, the poem's opening statement comes across as direct and authoritative, functioning as a brief break from both scripture and verse to establish the speaker's credibility. It also contains three stressed syllables in a row, which fall on "the great plane trees," immediately establishing the poem's subject.

The speaker goes on to list all of the sounds that emanate from the demolition site. These lines heavily feature onomatopoeic language, including “grate,” “crash,” “swish,” and “rustle,” words whose sounds seems to imitate what they describe. The noises that these words imitate resound throughout the stanza due to assonance and consonance:

For days there has been the grate of the saw, the swish of the branches as they fall,

The crash of the trunks, the rustle of trodden leaves,Sibilant /s/, /z/, and /sh/ sounds clash with cacophonous /t/ and /k/ sounds here and elsewhere throughout the poem. The tension between hard and soft that they create mirrors the workers’ cruel interruption of nature’s beauty. Additionally, the homophone pair “grate” and “great” as well as the men’s “Whoops” and “Whoas” contribute to the chorus of discordant sounds.

The speaker uses ambiguous language such as “a garden” and “the men,” which reflects the commonness of the images that the speaker describes. Plus, the sounds listed above could originate from any number of worksites. Therefore, the dense, layered cluster of sounds adds a sense of dimension to the setting, while allowing the reader’s imagination and memory to fill in the gaps. Sound will continue to play a central role in characterizing the poem’s setting and establishing its mood.

The ongoing activity indicated by phrases like “for days” and “they are cutting” emphasizes the drawn-out nature of the demolition and hints at the trees’ ultimate fate. Repetition in the form of parallelism and anaphora stylistically reflects this idea of continuing action. The parallel sentence structure in lines 2-3 within “grate of the," "swish of the,” etc. creates a repeating metrical pattern. Each phrase features an iamb followed by an anapest (unstressed stressed | unstressed unstressed stressed):

For days | there has been | the grate | of the saw, | the swish | of the bran- | ches as | they fall

The crash | of the trunks, | the rus- | tle of trod- | den leaves,These repeating stress patterns build momentum and anticipation, driving the poem forward.

Meanwhile, caesurae distinguish each sound and instance of parallelism, while asyndeton strings them together so that they flow into one another without any conjunctions, creating an echoing chorus. The repetition in line 4 also amplifies the workers’ “loud common talk” and makes it more “common” via repetition, ensuring that the workers' presence is felt.

|

PDF downloads of all 3057 of our lit guides, poetry guides, Shakescleare translations, and literary terms.

PDF downloads of all 1913 LitCharts literature guides, and of every new one we publish.

Learn more

|

|

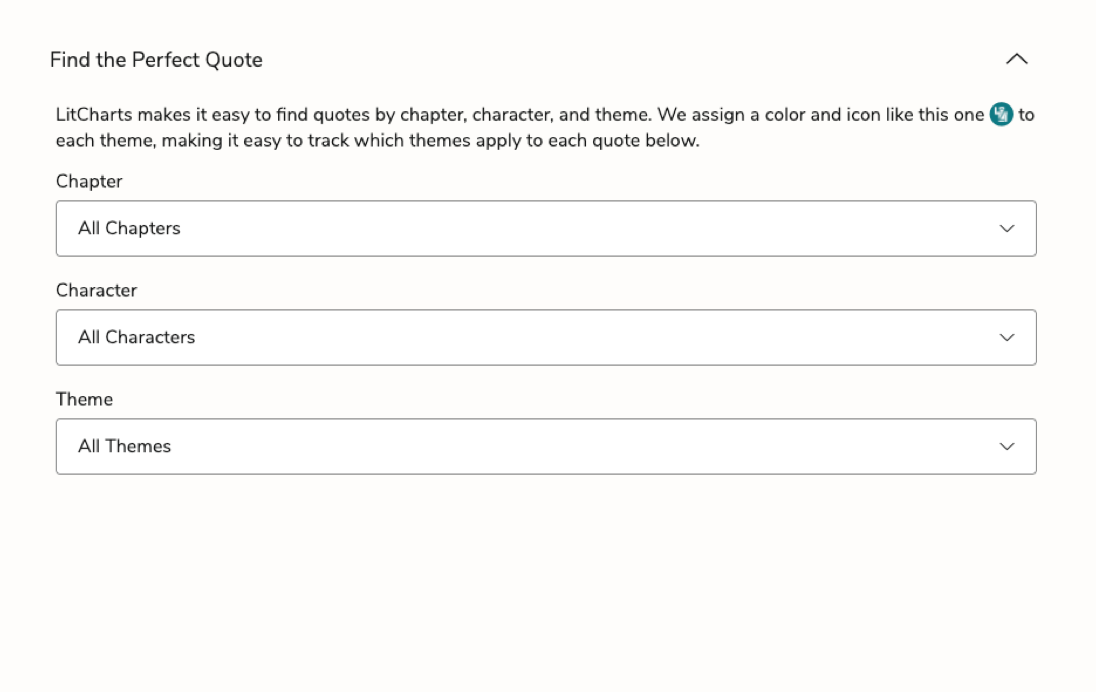

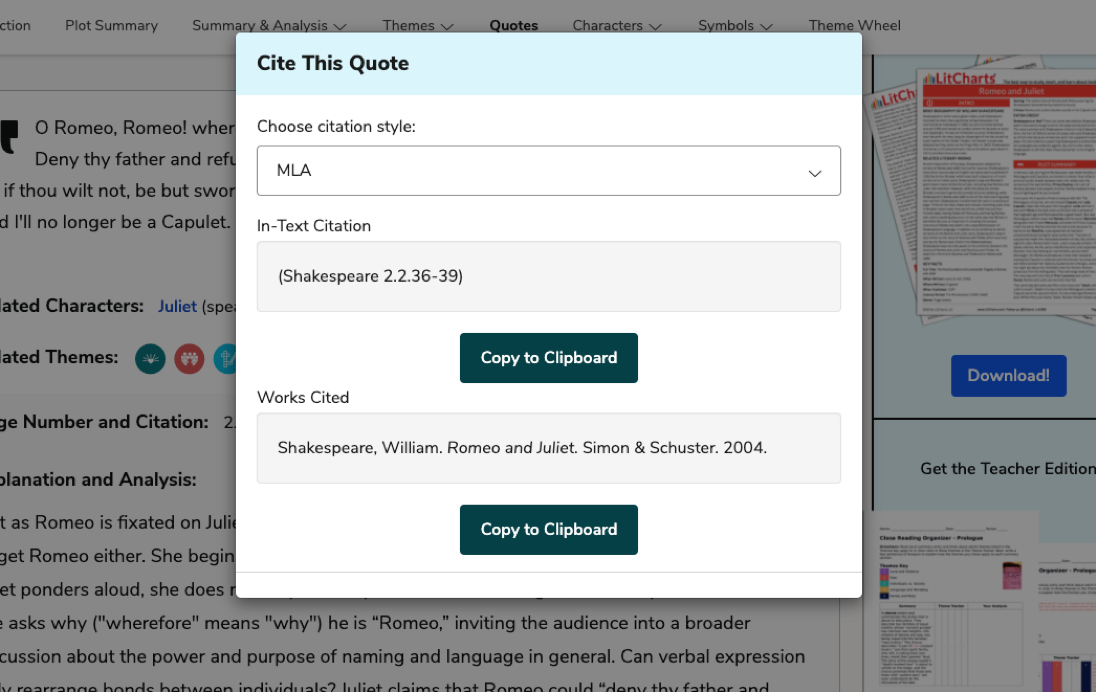

Explanations for every quote we cover.

Detailed quotes explanations (and citation info) for every important quote on the site.

Learn more

|

|

Instant PDF downloads of 136 literary devices and terms.

Definitions and examples for 136 literary devices and terms. Instant PDF downloads.

Learn more

|

|

Compare and contrast related themes.

Compare and contrast Related Themes across different books.

Learn more

|

|

Teacher Editions for all 1913 titles we cover.

LitCharts Teacher Editions for every title we cover.

Learn more

|

|

PDFs of modern translations of every Shakespeare play and poem.

PDFs of modern translations of every Shakespeare play and poem.

Learn more

|

|

Advanced search across our collection.

Advanced Search. Find themes, quotes, symbols, and characters across our collection.

Learn more

|

|

Line-by-line explanations, plus analysis of poetic devices for lyric poems we cover.

Line-by-line explanations, plus analysis of poetic devices for every lyric poem we cover.

Learn more

|

For every lyric poem we cover.

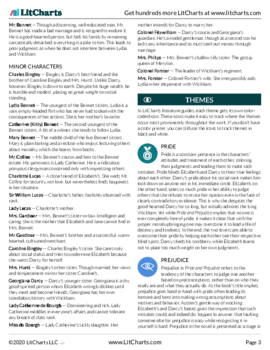

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Quotes Explanations

For all 42,307 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.