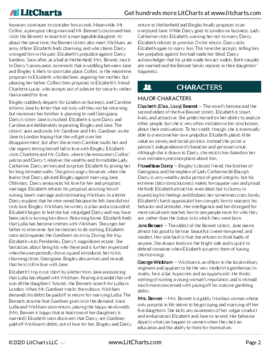

- All's Well That Ends Well

- Antony and Cleopatra

- As You Like It

- The Comedy of Errors

- Coriolanus

- Cymbeline

- Hamlet

- Henry IV, Part 1

- Henry IV, Part 2

- Henry V

- Henry VI, Part 1

- Henry VI, Part 2

- Henry VI, Part 3

- Henry VIII

- Julius Caesar

- King John

- King Lear

- Love's Labor's Lost

- A Lover's Complaint

- Macbeth

- Measure for Measure

- The Merchant of Venice

- The Merry Wives of Windsor

- A Midsummer Night's Dream

- Much Ado About Nothing

- Othello

- Pericles

- The Rape of Lucrece

- Richard II

- Richard III

- Romeo and Juliet

- Shakespeare's Sonnets

- The Taming of the Shrew

- The Tempest

- Timon of Athens

- Titus Andronicus

- Troilus and Cressida

- Twelfth Night

- The Two Gentlemen of Verona

- Venus and Adonis

- The Winter's Tale

plus so much more...

-

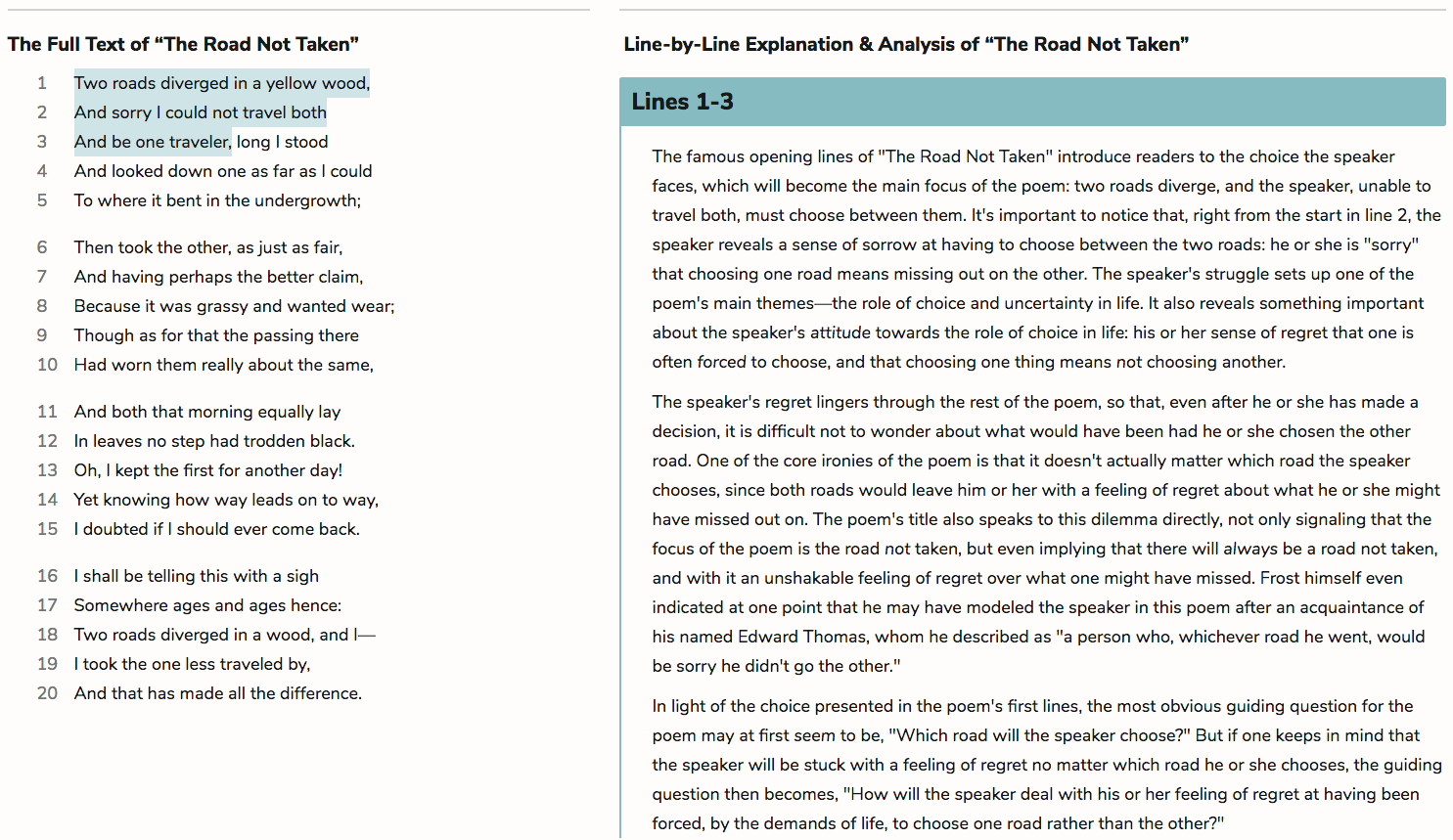

Lines 1-7

As the title suggests, the speaker of "Crusoe in England" is the castaway Robinson Crusoe, from Daniel Defoe's famous 1719 novel of the same title. In other words, this poem is a dramatic monologue: it's spoken in the voice of a character who is not the poet. It's also a very loose adaptation of its source material: Bishop changes Crusoe's character, setting, and story in many key respects. The poem's opening lines start to establish her Crusoe: the original spin she will bring to this classic tale.

The title also makes clear that Crusoe is narrating this poem from back home "in England." In other words, he's no longer trapped on a desert island. He's re-immersed in civilization, even plugged in to the media landscape. In fact, he begins by mentioning some news he's recently read in "the papers." This news turns out to relate to his former island—which, in Bishop's version of the story, was volcanic.

First, Crusoe reports that "A new volcano has erupted" somewhere in the world. Then, he recounts that "last week I was reading / where some ship saw an island being born." Evidently, this island was "born" from a separate, undersea volcanic eruption. (Islands formed in this way are known as high islands or volcanic islands.) Crusoe describes what the ship's crew witnessed: "first a breath of steam, ten miles away," followed by the appearance of a "black fleck," likely made of the volcanic rock called "basalt." (Basalt forms from cooling and hardening lava.) This fleck looked as small as a "fly" through the "binoculars" of the ship's "mate" (second-in-command) and seemed to catch "on the horizon" as if sticking to flypaper.

This striking imagery—including the vivid "fly" simile—immediately puts Crusoe's whole adventure into a broad perspective. As someone who lived on a volcanic island for many years, it's natural that Crusoe should follow news about volcanoes and islands. But what these "new" events seem to signify, on a symbolic level, is that the world has moved on from his ordeal. The metaphorical birth of the volcanic island is like the birth of a younger generation: a reminder of time's passage.

Moreover, the new island looks as puny as a fly from just ten miles' distance. This perspective suggests that Crusoe's great adventure—the whole drama he lived out on his island—might also be puny and trivial in the grander scheme of things. And the same might be true of anyone's solitary struggle, or anyone's whole existence. (Notice how the word "born" sets up an implied analogy between an island and an individual life.)

Before diving into his own tale, then, Crusoe seems to suggest that it's not really all that special. Islands come and go—and so do human struggles like his. On the geological timescale of the earth, these events are as ordinary and minuscule as the birth and death of flies.

|

PDF downloads of all 3060 of our lit guides, poetry guides, Shakescleare translations, and literary terms.

PDF downloads of all 1915 LitCharts literature guides, and of every new one we publish.

Learn more

|

|

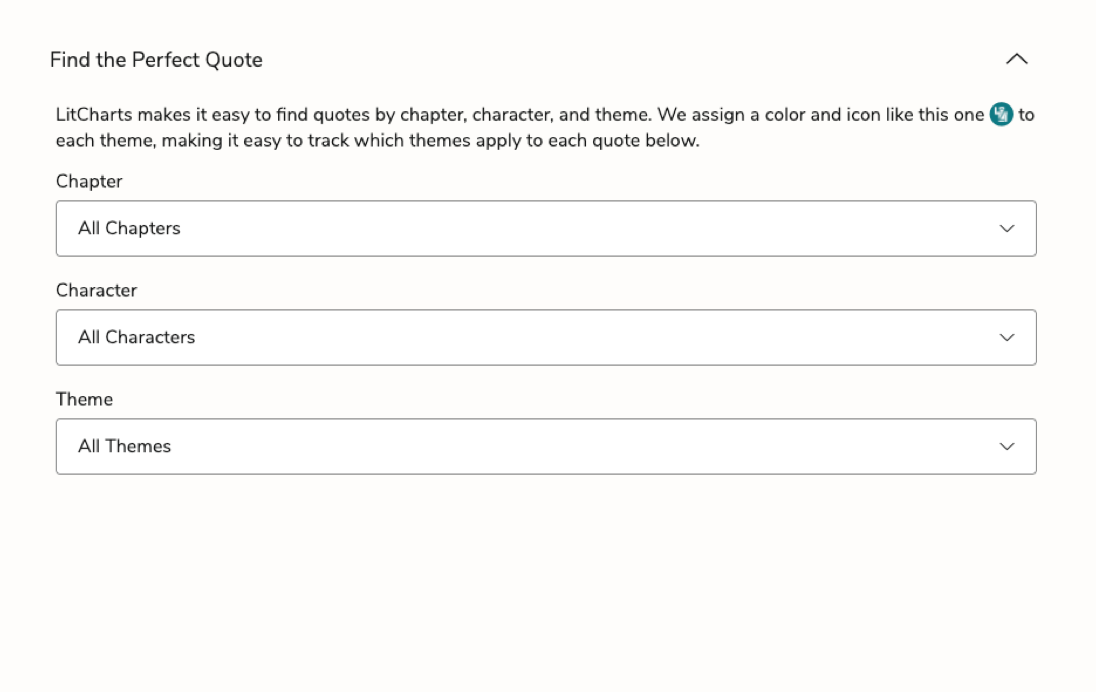

Explanations for every quote we cover.

Detailed quotes explanations (and citation info) for every important quote on the site.

Learn more

|

|

Instant PDF downloads of 136 literary devices and terms.

Definitions and examples for 136 literary devices and terms. Instant PDF downloads.

Learn more

|

|

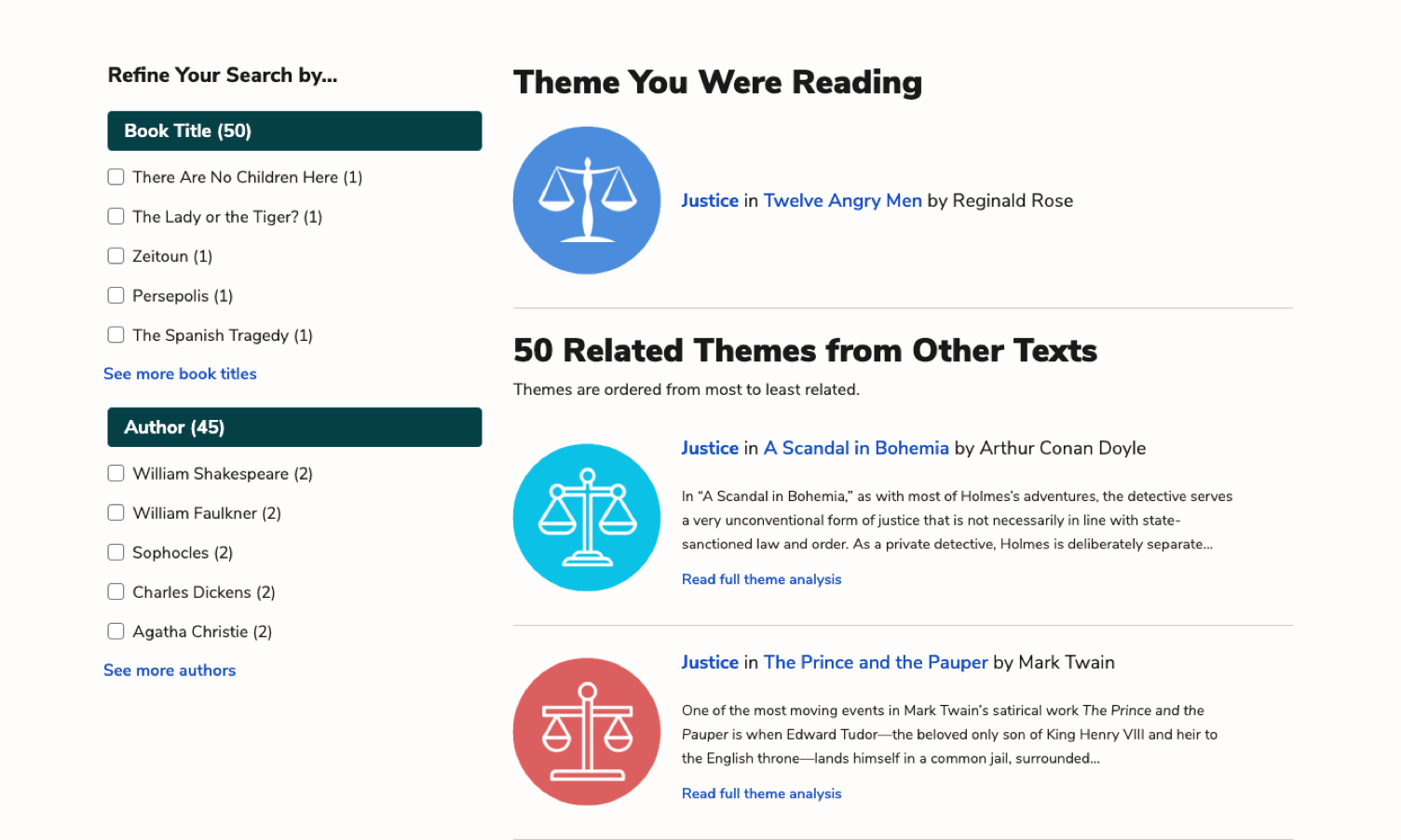

Compare and contrast related themes.

Compare and contrast Related Themes across different books.

Learn more

|

|

Teacher Editions for all 1915 titles we cover.

LitCharts Teacher Editions for every title we cover.

Learn more

|

|

PDFs of modern translations of every Shakespeare play and poem.

PDFs of modern translations of every Shakespeare play and poem.

Learn more

|

|

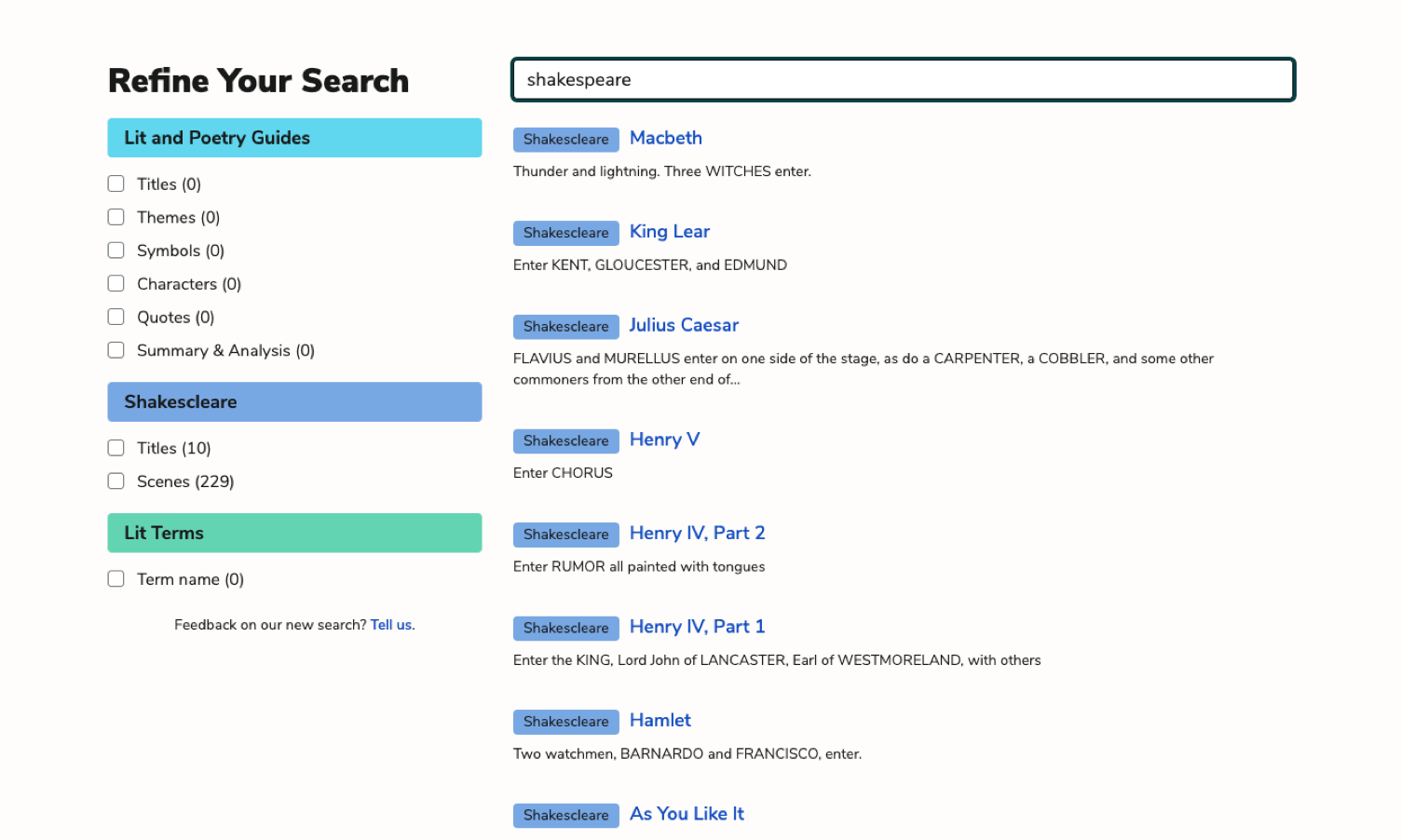

Advanced search across our collection.

Advanced Search. Find themes, quotes, symbols, and characters across our collection.

Learn more

|

|

Line-by-line explanations, plus analysis of poetic devices for lyric poems we cover.

Line-by-line explanations, plus analysis of poetic devices for every lyric poem we cover.

Learn more

|

For every lyric poem we cover.

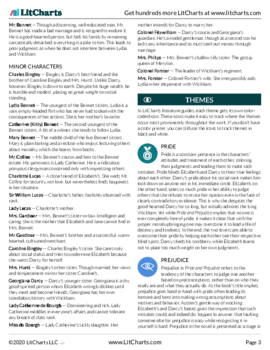

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Quotes Explanations

For all 42,357 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.