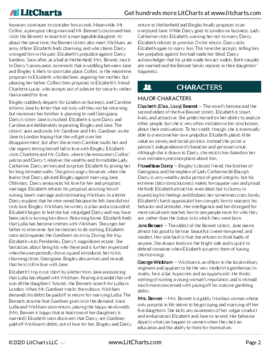

- All's Well That Ends Well

- Antony and Cleopatra

- As You Like It

- The Comedy of Errors

- Coriolanus

- Cymbeline

- Hamlet

- Henry IV, Part 1

- Henry IV, Part 2

- Henry V

- Henry VI, Part 1

- Henry VI, Part 2

- Henry VI, Part 3

- Henry VIII

- Julius Caesar

- King John

- King Lear

- Love's Labor's Lost

- A Lover's Complaint

- Macbeth

- Measure for Measure

- The Merchant of Venice

- The Merry Wives of Windsor

- A Midsummer Night's Dream

- Much Ado About Nothing

- Othello

- Pericles

- The Rape of Lucrece

- Richard II

- Richard III

- Romeo and Juliet

- Shakespeare's Sonnets

- The Taming of the Shrew

- The Tempest

- Timon of Athens

- Titus Andronicus

- Troilus and Cressida

- Twelfth Night

- The Two Gentlemen of Verona

- Venus and Adonis

- The Winter's Tale

plus so much more...

-

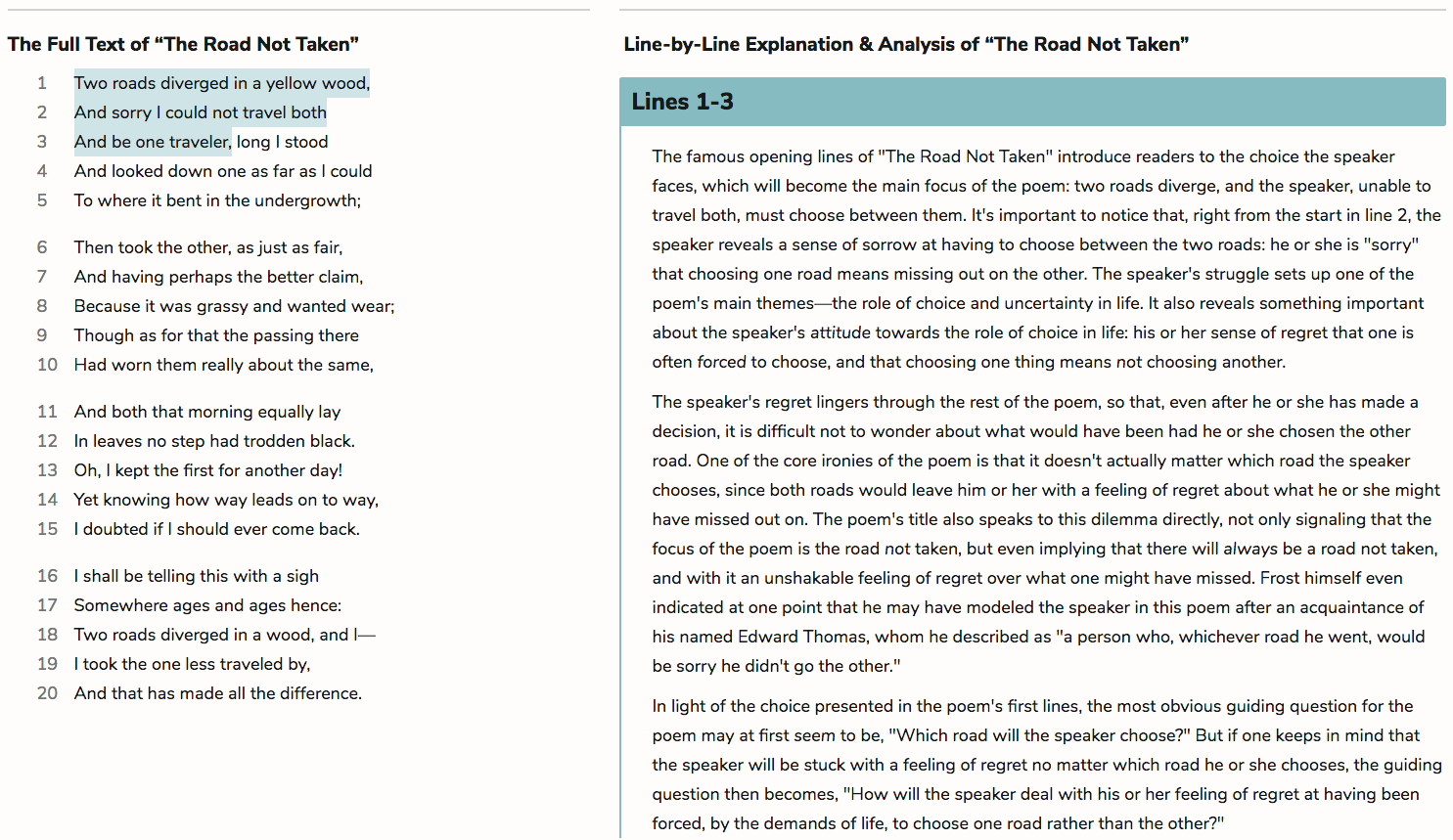

Lines 1-6

"Love (III)," as its title suggests, is the third poem on love in George Herbert's collection of Christian verse, The Temple. It's also the last poem in that book and can be taken, in some sense, as Herbert's final word on the matter. The love in question here isn't romantic love, but divine love: God's love for humanity, and for one anxious soul in particular.

That poor soul, the speaker himself, first appears standing at God's front door. But he's simply too ashamed to come in. Though God, in the form of Love personified, cheerily welcomes him, he shrinks away, feeling "guilty of dust and sin": in other words, on God's threshold, he's painfully aware of his own grimy mortal failings. Being this close to Love itself seems to have made him self-conscious.

God, "quick-eyed," notices the speaker’s hesitation, and greets him, "sweetly" asking "if I lacked anything." To a modern reader, this question just sounds makes God sound friendly, like a good host. To Herbert, these words would also suggest something more specific: "What do you lack?" is what a 17th-century bartender would ask a customer, something in the vein of "What can I get you?" In these lines, God appears as a kindly innkeeper, practically wiping their hands on their apron as they check on their nervous guest.

Right from the start, then, the poem layers gentle humor on top of awe (a classic Herbert move). The speaker, encountering God face to face, finds himself horribly aware of the stains on his own soul. But this momentous encounter happens in the earthliest of contexts.

As is often the case in Herbert, the poem's shape reflects its emotion:

- The poem's meter alternates between long lines of iambic pentameter (that is, lines of five iambs, metrical feet with a da-DUM rhythm: "Love bade | me wel- | come: yet | my soul | drew back") and short lines of iambic trimeter (just three iambs: "Who made | the eyes | but I?").

- The lines thus move like the relationship the poem describes: God reaches out to welcome the speaker, the speaker shrinks away in shame.

- The rhyme scheme works similarly: in each sestet (or six-line stanza), a dithery alternating ABAB pattern resolves in a firm CC couplet, just as God replies to the speaker's hesitance with a firm welcome.

The poem's music makes meaning, too. Listen to the echoing sounds in the first lines:

Love bade me welcome: yet my soul drew back,

Guilty of dust and sin.The alliterative and assonant chime between "bade" (pronounced bad) and "back" again meets God's welcome with the speaker's reluctance. And the sibilant /s/ running through "soul," "dust," and "sin" links the speaker's soul with all that he feels stains it.

Those stains don't matter to the innkeeper Love, though. This will be a poem about a God whose love and forgiveness are so far and beyond human capacities that they boggle the mind of even the most fervent believer.

|

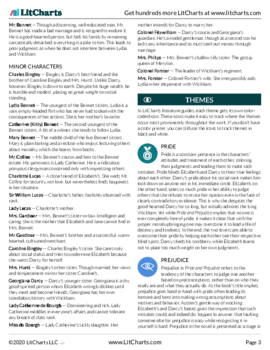

PDF downloads of all 3053 of our lit guides, poetry guides, Shakescleare translations, and literary terms.

PDF downloads of all 1909 LitCharts literature guides, and of every new one we publish.

Learn more

|

|

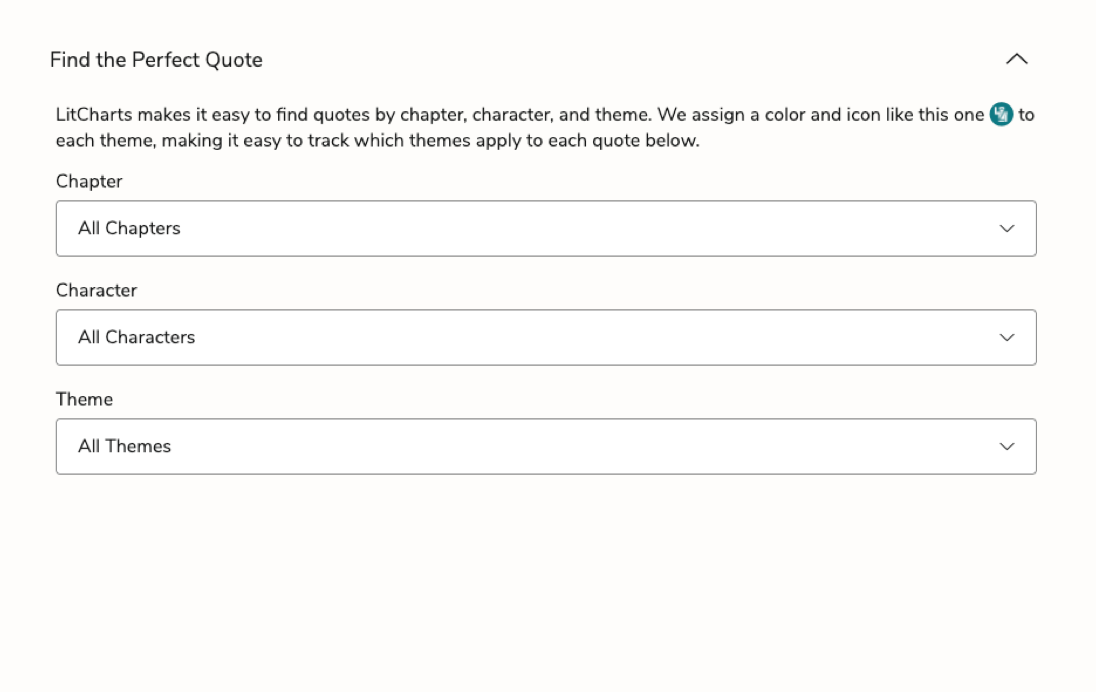

Explanations for every quote we cover.

Detailed quotes explanations (and citation info) for every important quote on the site.

Learn more

|

|

Instant PDF downloads of 136 literary devices and terms.

Definitions and examples for 136 literary devices and terms. Instant PDF downloads.

Learn more

|

|

Compare and contrast related themes.

Compare and contrast Related Themes across different books.

Learn more

|

|

Teacher Editions for all 1909 titles we cover.

LitCharts Teacher Editions for every title we cover.

Learn more

|

|

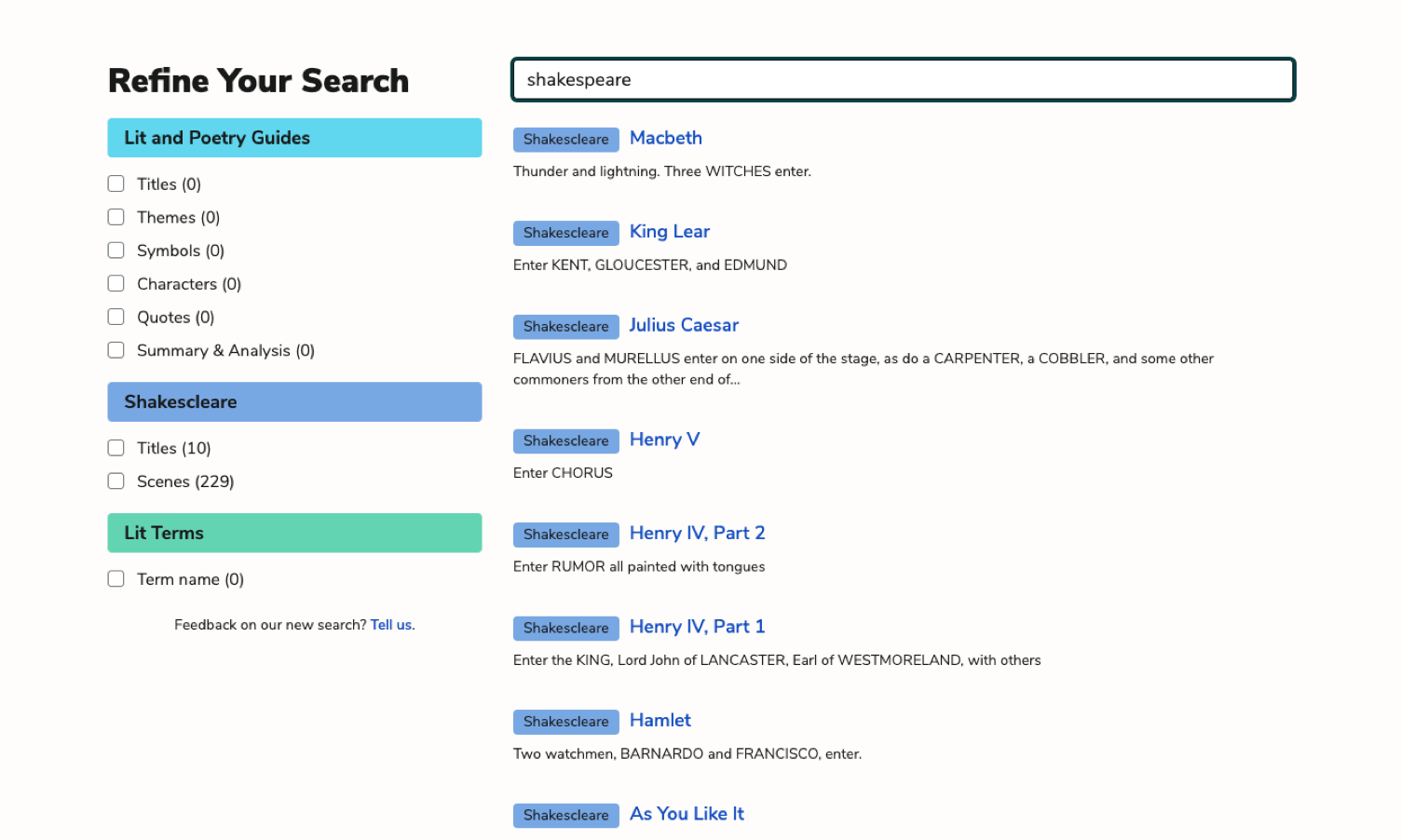

PDFs of modern translations of every Shakespeare play and poem.

PDFs of modern translations of every Shakespeare play and poem.

Learn more

|

|

Advanced search across our collection.

Advanced Search. Find themes, quotes, symbols, and characters across our collection.

Learn more

|

|

Line-by-line explanations, plus analysis of poetic devices for lyric poems we cover.

Line-by-line explanations, plus analysis of poetic devices for every lyric poem we cover.

Learn more

|

For every lyric poem we cover.

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Quotes Explanations

For all 42,208 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.