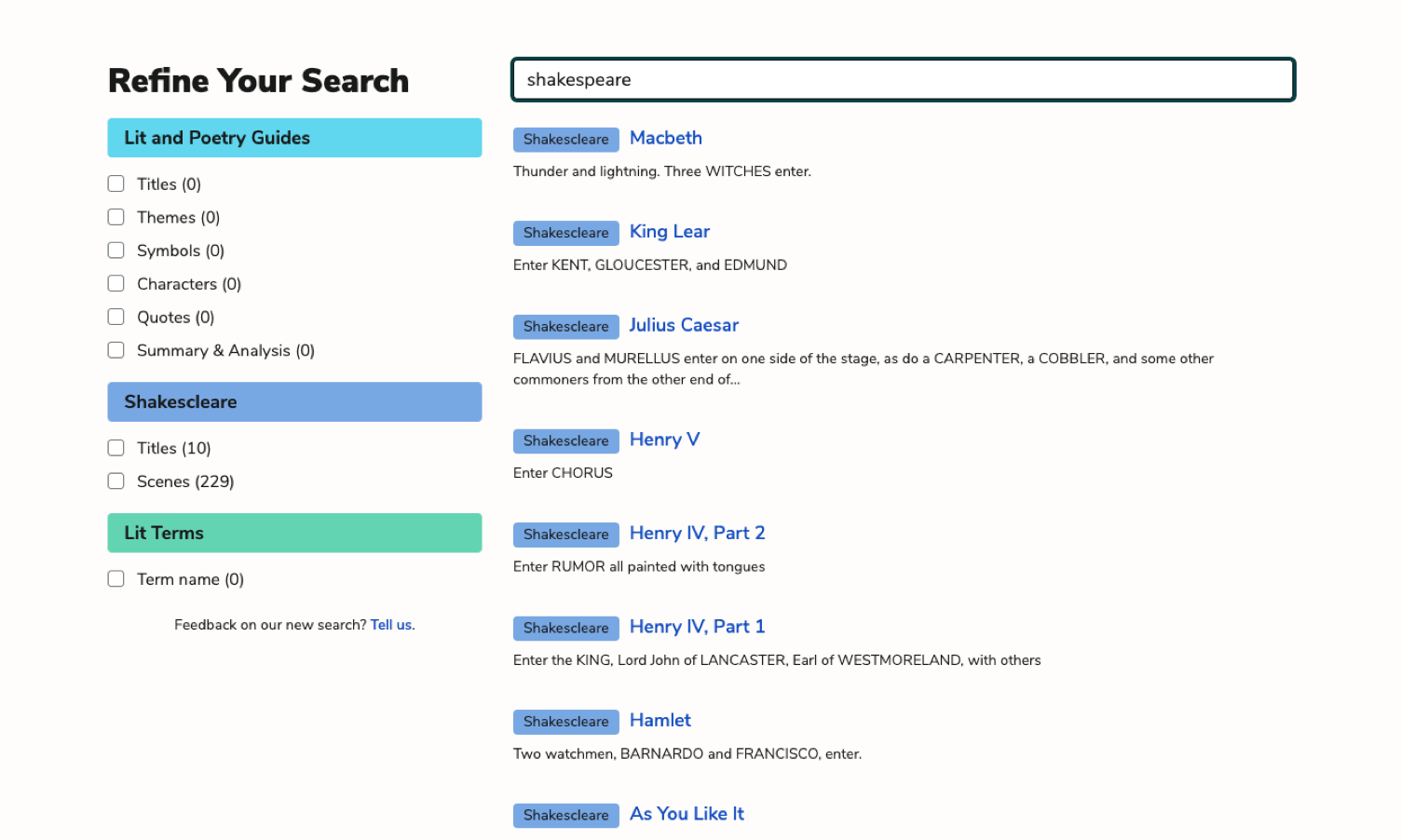

- All's Well That Ends Well

- Antony and Cleopatra

- As You Like It

- The Comedy of Errors

- Coriolanus

- Cymbeline

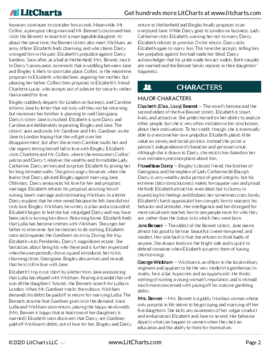

- Hamlet

- Henry IV, Part 1

- Henry IV, Part 2

- Henry V

- Henry VI, Part 1

- Henry VI, Part 2

- Henry VI, Part 3

- Henry VIII

- Julius Caesar

- King John

- King Lear

- Love's Labor's Lost

- A Lover's Complaint

- Macbeth

- Measure for Measure

- The Merchant of Venice

- The Merry Wives of Windsor

- A Midsummer Night's Dream

- Much Ado About Nothing

- Othello

- Pericles

- The Rape of Lucrece

- Richard II

- Richard III

- Romeo and Juliet

- Shakespeare's Sonnets

- The Taming of the Shrew

- The Tempest

- Timon of Athens

- Titus Andronicus

- Troilus and Cressida

- Twelfth Night

- The Two Gentlemen of Verona

- Venus and Adonis

- The Winter's Tale

plus so much more...

-

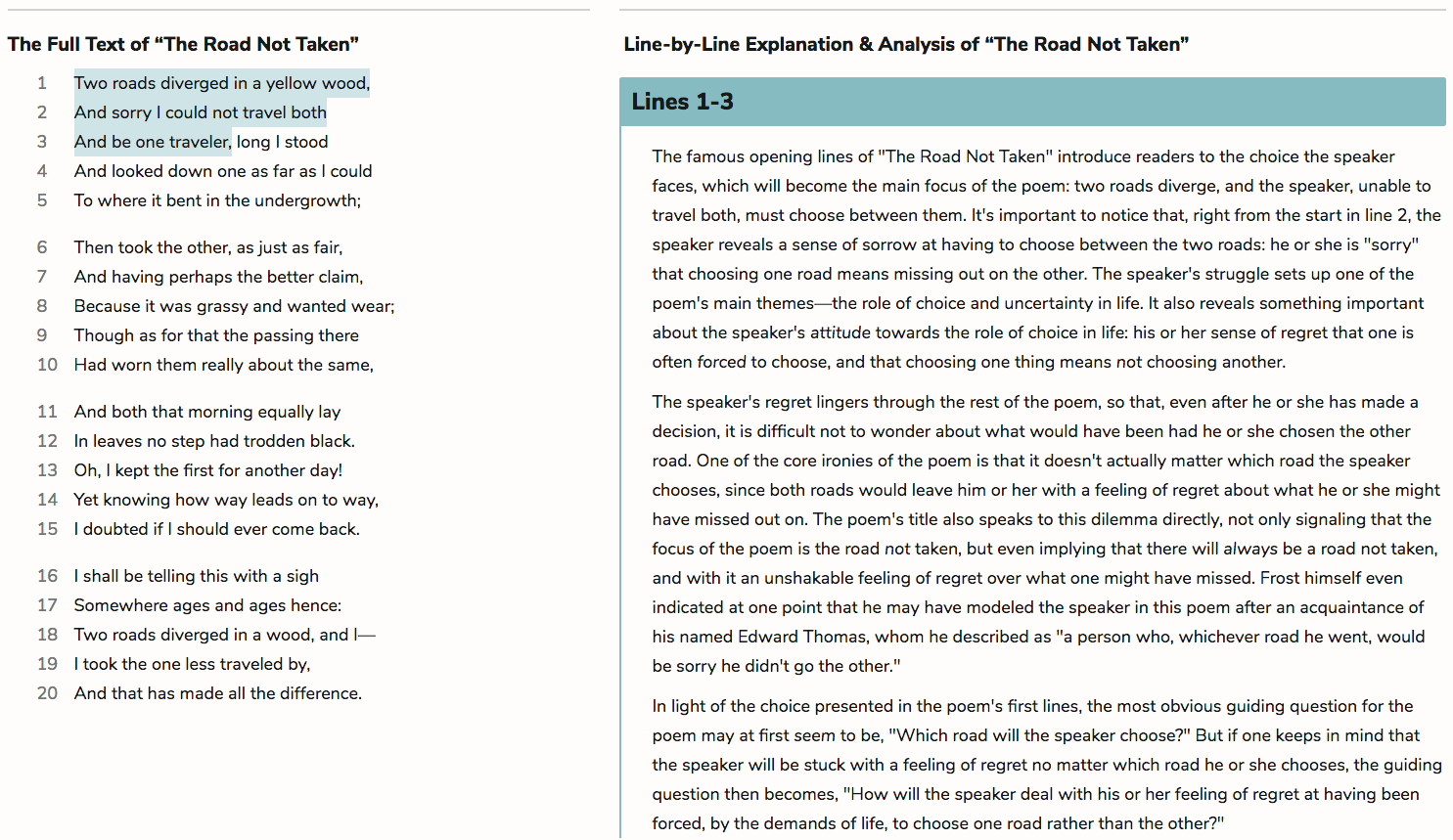

Lines 1-4

In "My Parents," the speaker recalls the difficulties of his upbringing. He was a middle- or upper-class child, though life frequently put him into contact with "children who were rough"—that is, working-class kids who lived in the same area. His parents, mentioned only in this first line, tried to keep him away from these other kids.

Already, this opening detail tells the reader a lot about the speaker's childhood. His parents believed he was vulnerable and needed their protection. They were also suspicious of, and likely condescending toward, people of lower economic classes. Placing "My parents" right at the start of the poem—even though the speaker never mentions them again—suggests how central their attitudes were to the speaker's childhood. Their distaste for "rough" children had a lasting impact on him; hence the need for this retrospective (and introspective) poem.

"Rough" is a euphemism here. It's a seemingly harmless word, but it does a lot of work. It's a way of saying "violent" or "brutish," while also suggesting a perceived lack of refinement (in accent, mannerisms, clothing, etc.). It's a typically middle- or upper-class way to describe someone of lower social status, particularly in the early 20th century.

The parents' attempts to shield the speaker from the "rough" kids didn't work. The rest of the poem focuses entirely on the speaker's interactions with these kids. As a way of capturing their "rough[ness]," the poem rejects conventional punctuation and sentence structure. Notice, for example, how the first line leads into the second:

My parents kept me from children who were rough

Who threw words like stones and wore torn clothesBecause the speaker omits the expected comma after "rough," the repetition of "Who" in line 2 is abrupt and surprising. The asyndeton between "rough" and "Who" (i.e., the lack of a conjunction such as "and") makes this shift from line to line especially startling. The language here sounds jerky and jagged, as "rough" as the kids it's describing.

The "rough" kids, according to the speaker, "threw words like stones." This simile alludes to an old nursery rhyme: "Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words may never hurt me." The speaker flips this idea on its head—the bullies' words did hurt, and they hurt so much that they felt like stones. They might not have broken his bones, but they did break his spirit.

The bullies' "torn clothes" and "rags" signal their poverty. In line 3, the speaker recalls how "their thighs showed through" their garments. The speaker often notes the physicality of these other children, conveying an appreciation of their strength and vigor. While he avoided them, they had a grand old time running around the street, "climb[ing] cliffs," and stripping "by the country streams." Though poor, they led active, exciting lives with a degree of freedom (though they probably had to work, too). The speaker's life, by contrast, was far more restrained. On some level, then, the speaker may have longed to be one of the "rough" children, even while internalizing his parents' message to keep away from them.

This first stanza captures the "rough[ness]" of those children not only through asyndeton but through sound patterning. Dense assonance ("Who threw," "stones and wore torn clothes," "cliffs"/"stripped") and alliteration ("words"/"wore," "thighs"/"through," "climbed cliffs [...] stripped by country streams") make the language sound robust and a little tough to say. The poem thus creates its own "rough" music to evoke the speaker's childhood fears.

|

PDF downloads of all 3060 of our lit guides, poetry guides, Shakescleare translations, and literary terms.

PDF downloads of all 1916 LitCharts literature guides, and of every new one we publish.

Learn more

|

|

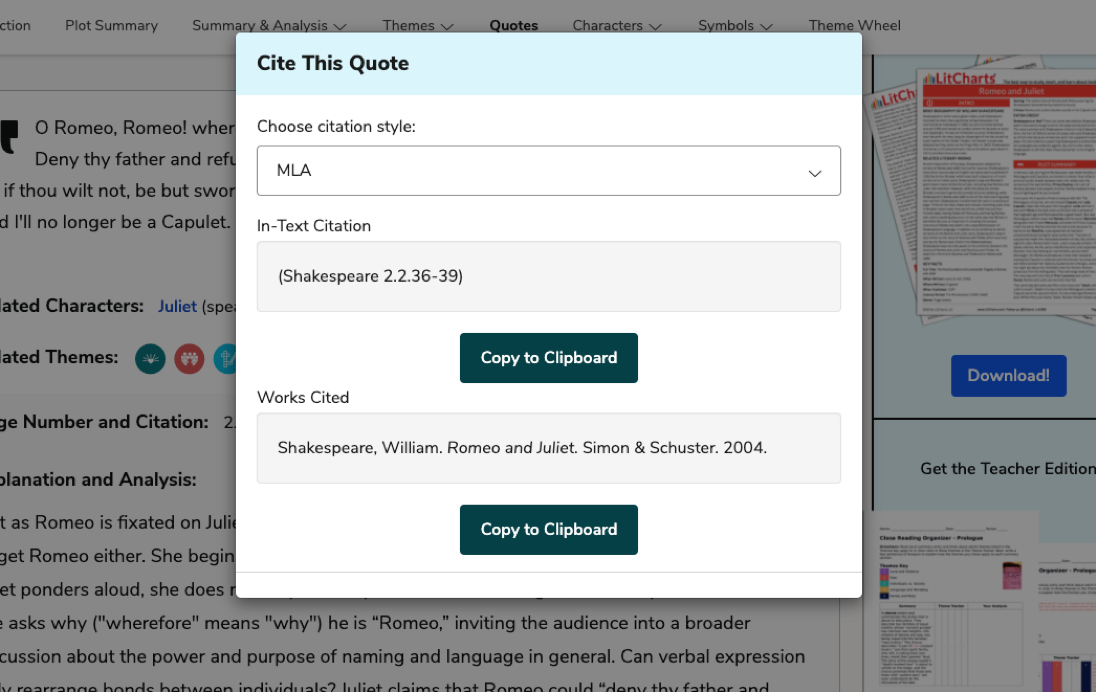

Explanations for every quote we cover.

Detailed quotes explanations (and citation info) for every important quote on the site.

Learn more

|

|

Instant PDF downloads of 136 literary devices and terms.

Definitions and examples for 136 literary devices and terms. Instant PDF downloads.

Learn more

|

|

Compare and contrast related themes.

Compare and contrast Related Themes across different books.

Learn more

|

|

Teacher Editions for all 1916 titles we cover.

LitCharts Teacher Editions for every title we cover.

Learn more

|

|

PDFs of modern translations of every Shakespeare play and poem.

PDFs of modern translations of every Shakespeare play and poem.

Learn more

|

|

Advanced search across our collection.

Advanced Search. Find themes, quotes, symbols, and characters across our collection.

Learn more

|

|

Line-by-line explanations, plus analysis of poetic devices for lyric poems we cover.

Line-by-line explanations, plus analysis of poetic devices for every lyric poem we cover.

Learn more

|

For every lyric poem we cover.

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Quotes Explanations

For all 42,382 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.