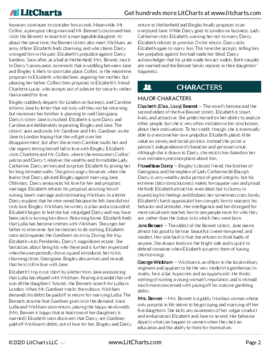

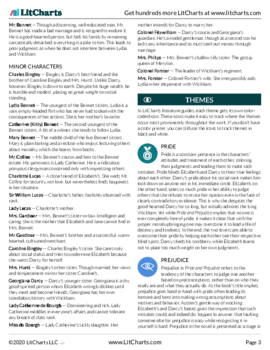

- All's Well That Ends Well

- Antony and Cleopatra

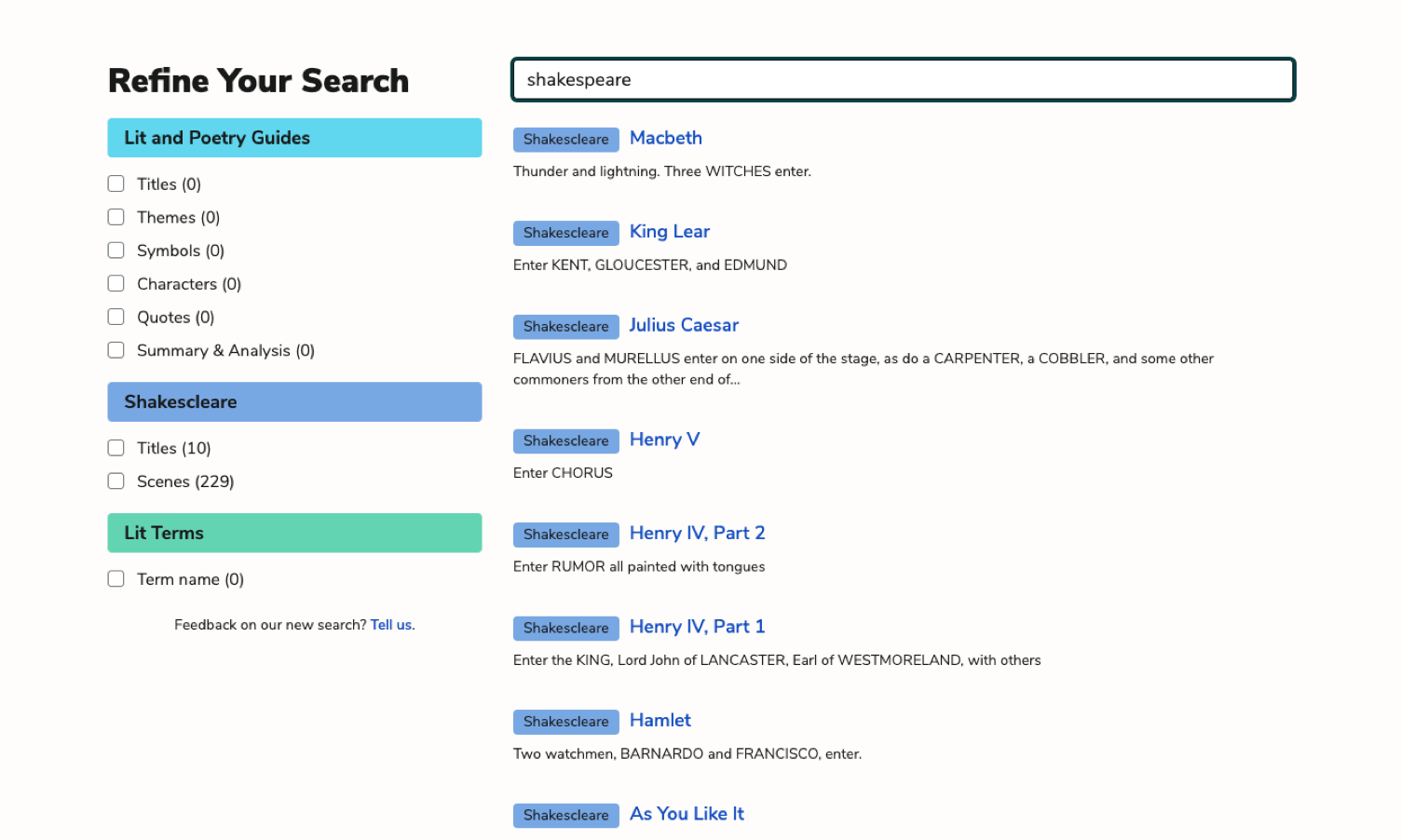

- As You Like It

- The Comedy of Errors

- Coriolanus

- Cymbeline

- Hamlet

- Henry IV, Part 1

- Henry IV, Part 2

- Henry V

- Henry VI, Part 1

- Henry VI, Part 2

- Henry VI, Part 3

- Henry VIII

- Julius Caesar

- King John

- King Lear

- Love's Labor's Lost

- A Lover's Complaint

- Macbeth

- Measure for Measure

- The Merchant of Venice

- The Merry Wives of Windsor

- A Midsummer Night's Dream

- Much Ado About Nothing

- Othello

- Pericles

- The Rape of Lucrece

- Richard II

- Richard III

- Romeo and Juliet

- Shakespeare's Sonnets

- The Taming of the Shrew

- The Tempest

- Timon of Athens

- Titus Andronicus

- Troilus and Cressida

- Twelfth Night

- The Two Gentlemen of Verona

- Venus and Adonis

- The Winter's Tale

plus so much more...

-

Alliteration

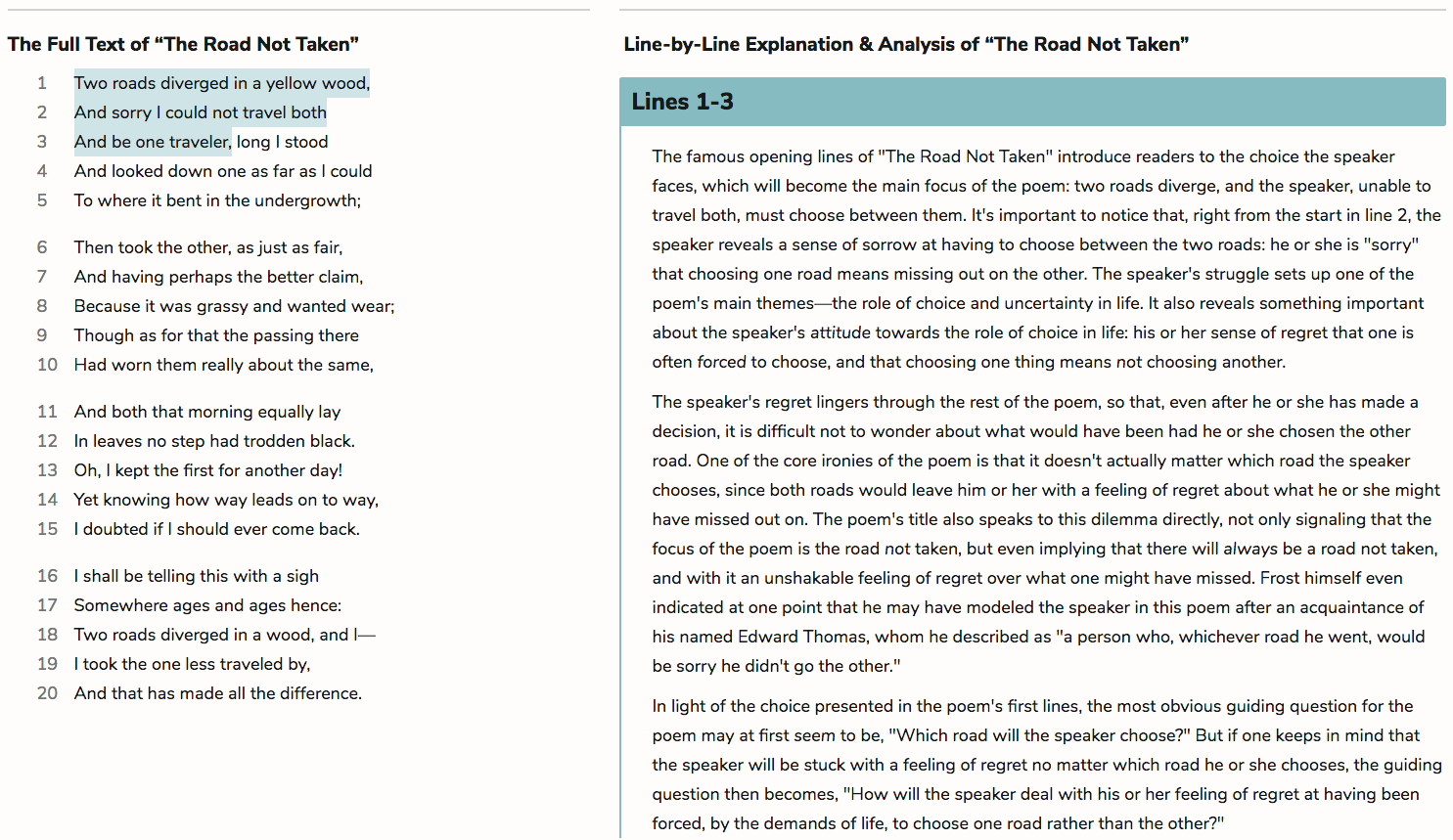

The first stanza of “Success is Counted Sweetest” makes frequent use of alliteration, which, combined with sibilance and consonance, makes its moral message all the more memorable. This stanza is filled with repeated /s/ and /n/ sounds at the start of words.

The poem here is building a metaphor, mapping the idea of “success” onto taste (specifically, onto sweetness). The “sweet” taste of success is one best enjoyed—or one that would be best enjoyed—by those for whom it is most unattainable.

The next instance of alliteration is between “ne’er” and “nectar” (lines 2 and 3). These words look and sound very similar, with just the /ct/ added or taken away to make them sound the same. This places the two concepts close together: “ne’er,” which represents denial and failure, with “nectar,” which stands in for the sweet taste of success. This creates a “so-near-yet-so-far” effect, with “nectar” placed tantalizingly—but forever—out of reach. This then widens to include the “need” of line 4.

The other example of alliteration in “Success is Counted Sweetest” comes in line 9. Here, the two /d/ sounds of “defeated” and “dying” combine with caesura to create a sense of weariness and small, difficult movement in keeping with the description of a dying soldier. Indeed, the first and last syllables of “defeated” even create the word “dead.”

This alliteration also chimes with the /d/ in “distant,” which has a similar effect to the /n/ alliteration discussed in the paragraph above. The alliteration helps draw a distinction between the “dead” soldier in one place and the victorious “distant” army in another, showing that they are close in the sense that there are fine margins between victory and defeat but also far apart in terms of what it means to succeed or fail.

|

PDF downloads of all 3053 of our lit guides, poetry guides, Shakescleare translations, and literary terms.

PDF downloads of all 1909 LitCharts literature guides, and of every new one we publish.

Learn more

|

|

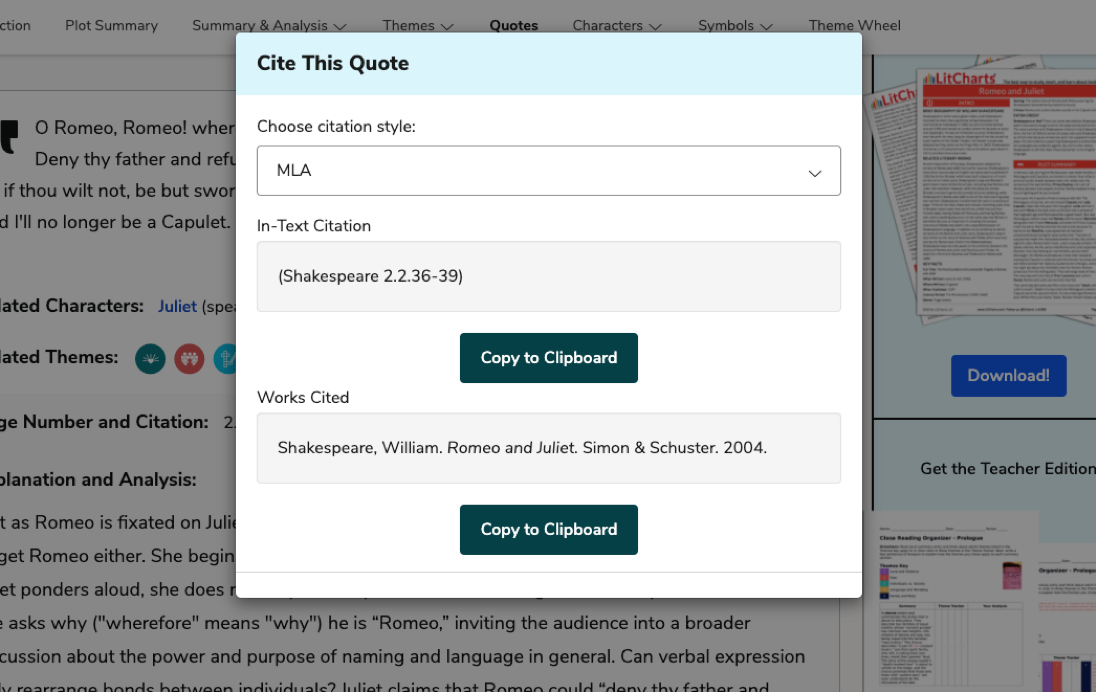

Explanations for every quote we cover.

Detailed quotes explanations (and citation info) for every important quote on the site.

Learn more

|

|

Instant PDF downloads of 136 literary devices and terms.

Definitions and examples for 136 literary devices and terms. Instant PDF downloads.

Learn more

|

|

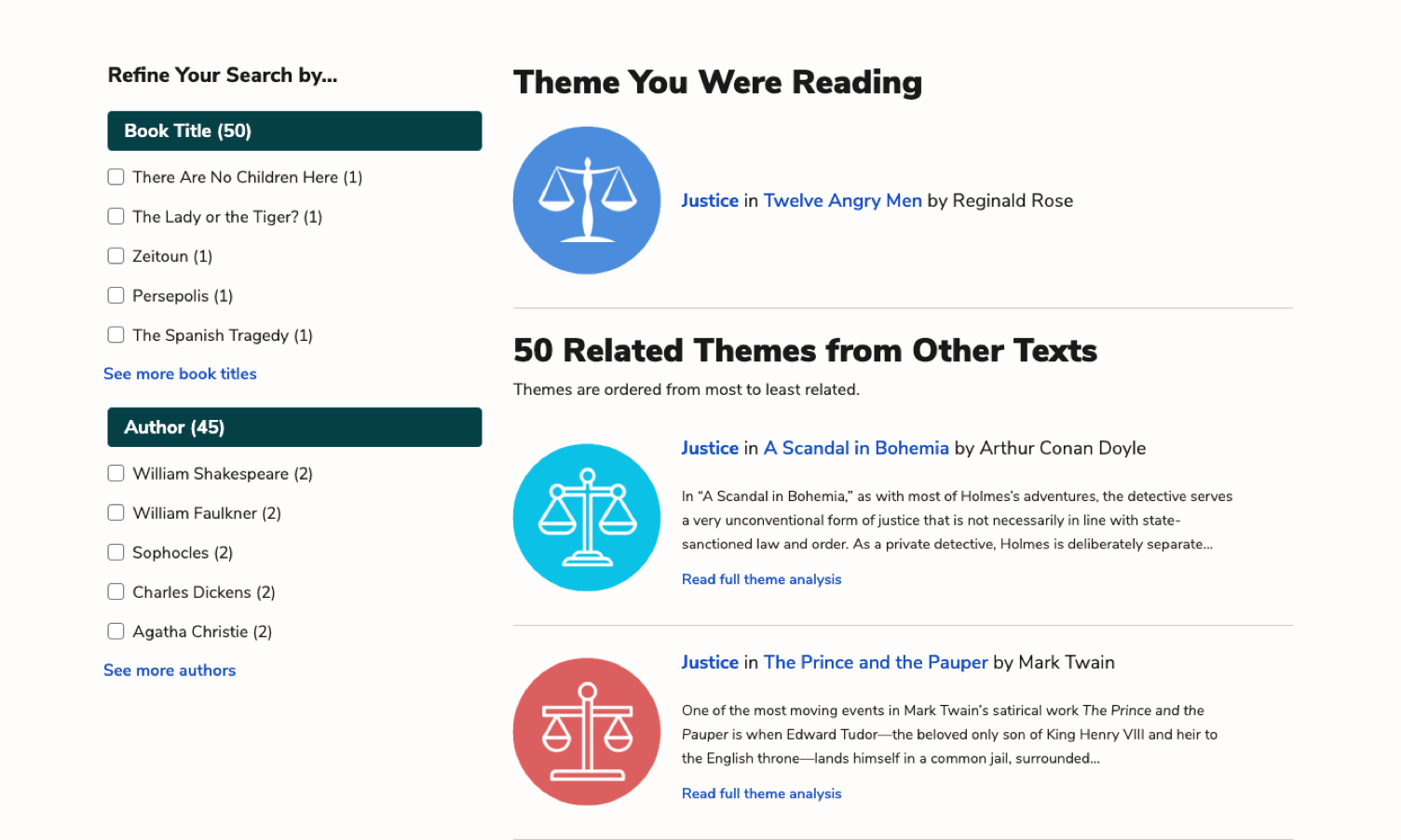

Compare and contrast related themes.

Compare and contrast Related Themes across different books.

Learn more

|

|

Teacher Editions for all 1909 titles we cover.

LitCharts Teacher Editions for every title we cover.

Learn more

|

|

PDFs of modern translations of every Shakespeare play and poem.

PDFs of modern translations of every Shakespeare play and poem.

Learn more

|

|

Advanced search across our collection.

Advanced Search. Find themes, quotes, symbols, and characters across our collection.

Learn more

|

|

Line-by-line explanations, plus analysis of poetic devices for lyric poems we cover.

Line-by-line explanations, plus analysis of poetic devices for every lyric poem we cover.

Learn more

|

For every lyric poem we cover.

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Quotes Explanations

For all 42,208 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.