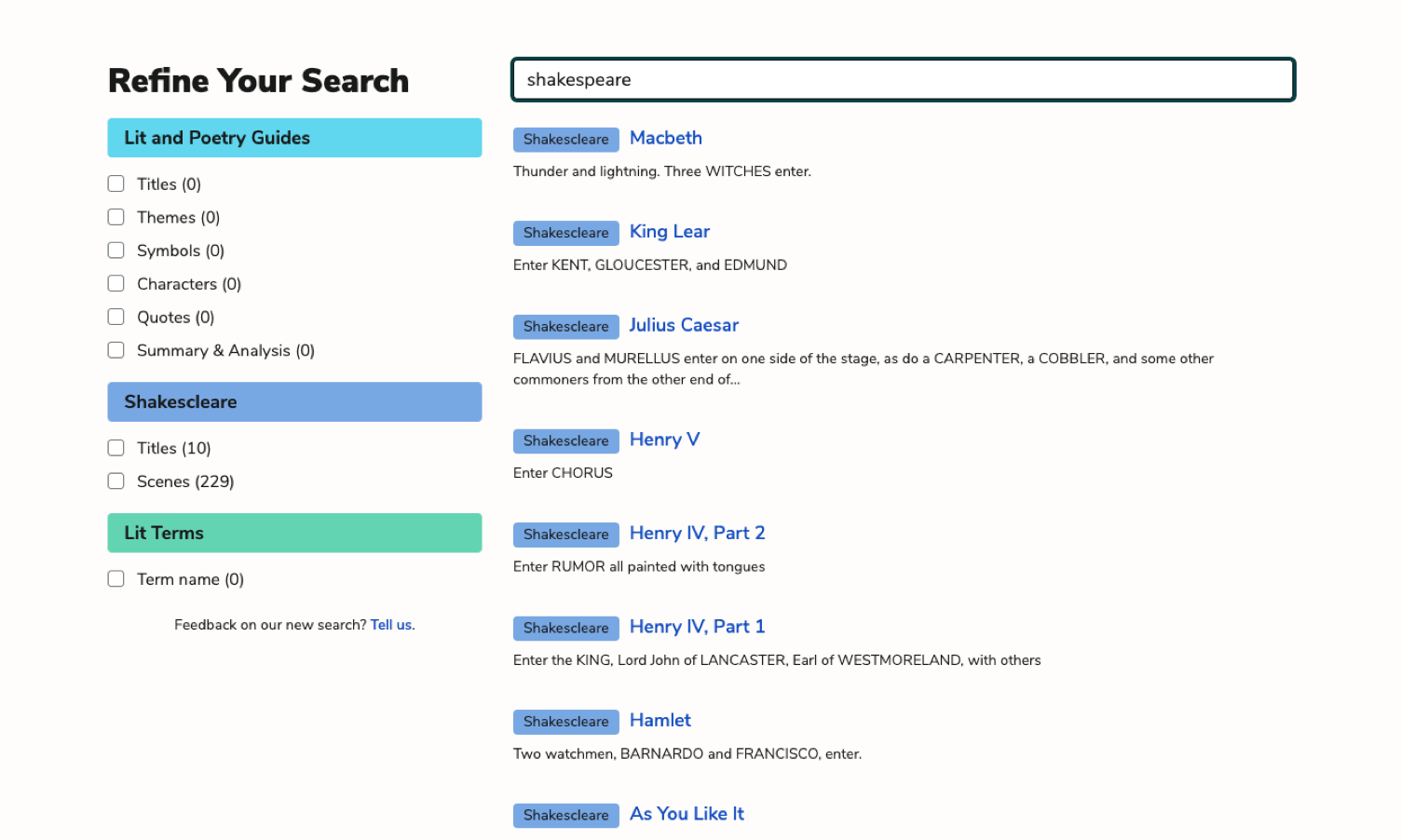

- All's Well That Ends Well

- Antony and Cleopatra

- As You Like It

- The Comedy of Errors

- Coriolanus

- Cymbeline

- Hamlet

- Henry IV, Part 1

- Henry IV, Part 2

- Henry V

- Henry VI, Part 1

- Henry VI, Part 2

- Henry VI, Part 3

- Henry VIII

- Julius Caesar

- King John

- King Lear

- Love's Labor's Lost

- A Lover's Complaint

- Macbeth

- Measure for Measure

- The Merchant of Venice

- The Merry Wives of Windsor

- A Midsummer Night's Dream

- Much Ado About Nothing

- Othello

- Pericles

- The Rape of Lucrece

- Richard II

- Richard III

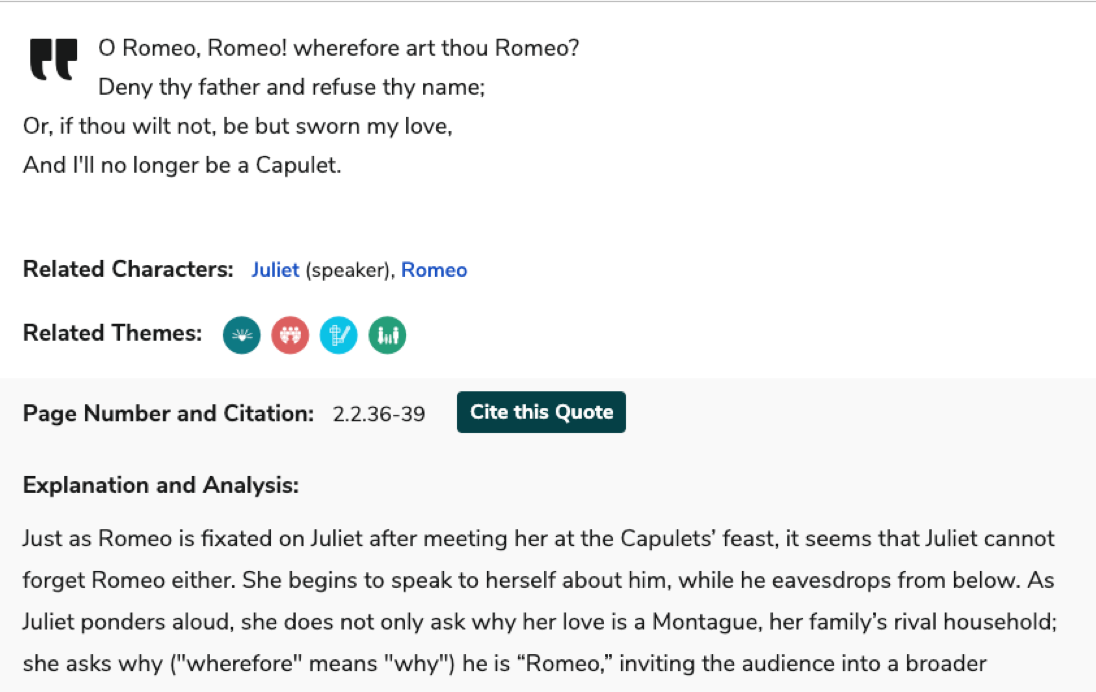

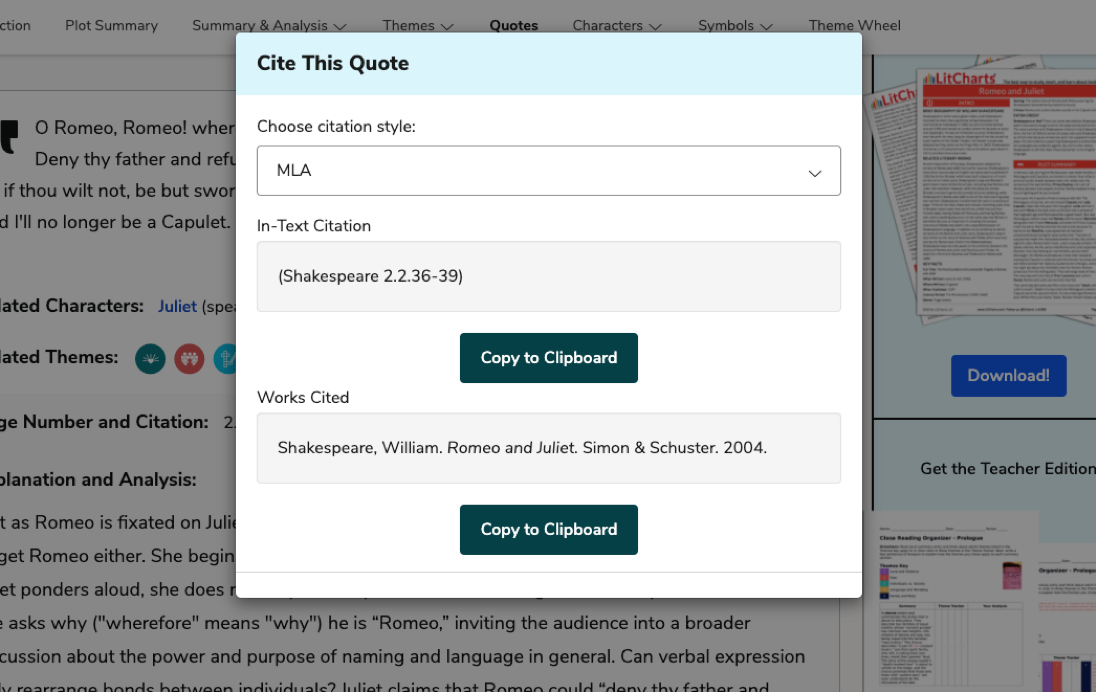

- Romeo and Juliet

- Shakespeare's Sonnets

- The Taming of the Shrew

- The Tempest

- Timon of Athens

- Titus Andronicus

- Troilus and Cressida

- Twelfth Night

- The Two Gentlemen of Verona

- Venus and Adonis

- The Winter's Tale

This quote occurs in scenario B, in which Mary pines after a rather indifferent John. Here Atwood illustrates how fundamentally unequal the sexual and romantic relationships between men and women can be: while John is free to pursue his own sexual pleasure and disregard Mary’s needs, Mary is stuck trying to please John in every aspect of their relationship, from the sexual to the mundane. In particular, Mary attempts to use sex “not because she likes sex exactly, she doesn’t,” but rather as a way to get John to depend on her. She does not focus on sex as an…