|

Have questions?

Contact us

Already a member? Sign in

|

Get every literary device explanation for LeviathanPlus so much more...

Sign up for LitCharts A+Get instant access to every literary device explanation, plus so much more...

Allegory

Explanation and Analysis—Colonies:

Further expanding upon his central allegory of the “body politic” (the collective body of the state), Hobbes considers the question of colonies, concluding that they are the “Children of a Common-wealth”:

The Procreation, or Children of a Common-wealth, are those we call Plantations, or Colonies; which are numbers of men sent out from the Common-wealth, under a Conductor, or Governour, to inhabit a Forraign Country [...] And when a Colony is setled, they are either a Common-wealth of themselves, discharged of their subjection to their Soveraign that sent them, (as hath been done by many Common-wealths of antient time,) in which case the Common-wealth from which they went was called their Metropolis, or Mother, and requires no more of them, then Fathers require of the Children [...] or else they remain united to their Metropolis.

Much as an individual body can procreate and bear children, so too can the collective body politic reproduce by establishing “Plantations, or Colonies,” sending its own citizens abroad in order to claim possession of some territory, either uninhabited or defeated by the colonists. He then further divides colonies into two types: those that “remain united” to the original state, and those that became a “Common-wealth of themselves” by casting off their original sovereign.

A state, Hobbes suggests, has no right to make any demands of a colony that has decided to become its own state, in much the same way that a father must accept that a child has reached adulthood and gained independence. This is one of many instances in the book of Hobbes developing his central allegory, examining various civil questions through the lens of the body.

Monthly

Annual (Best Value)

$595USD/mo

Charged $71.40 USD every year

Teacher

Teacher$795USD/mo

Charged $95.40 USD every year

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Instant PDF downloads of all 2247 LitCharts literature guides and of every new one we publish. Try a free sample literature guide.

"Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!"

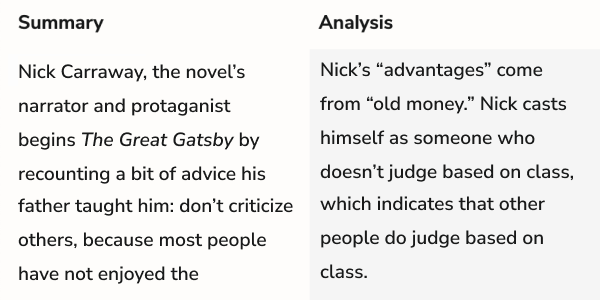

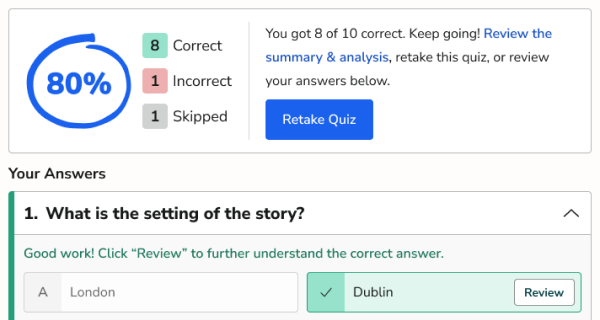

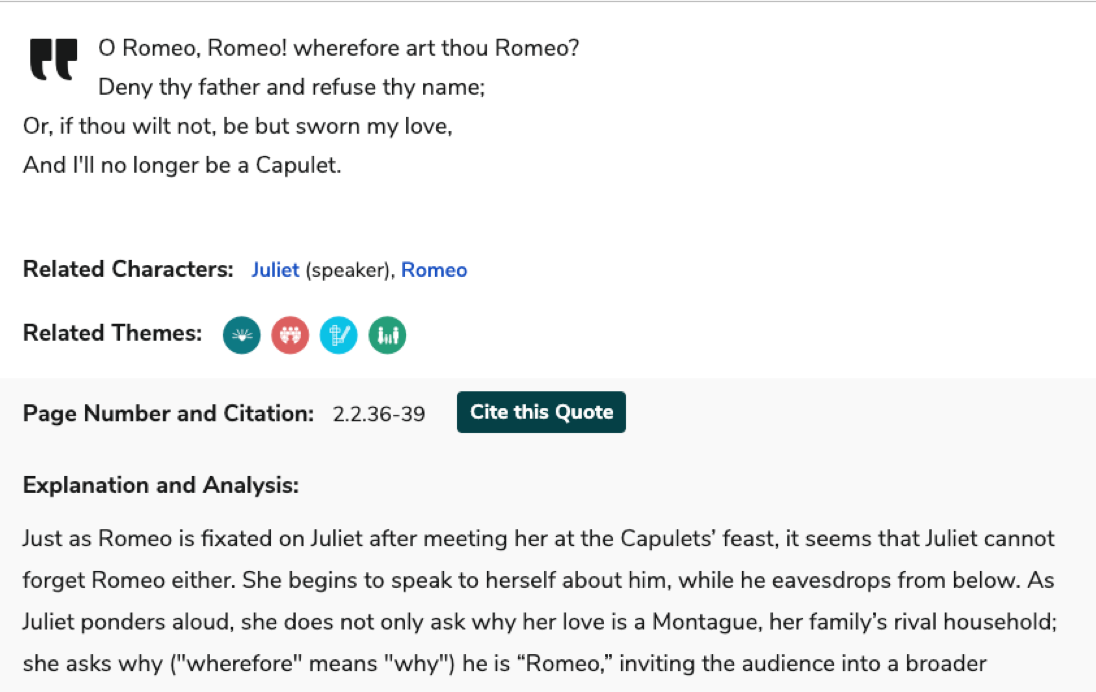

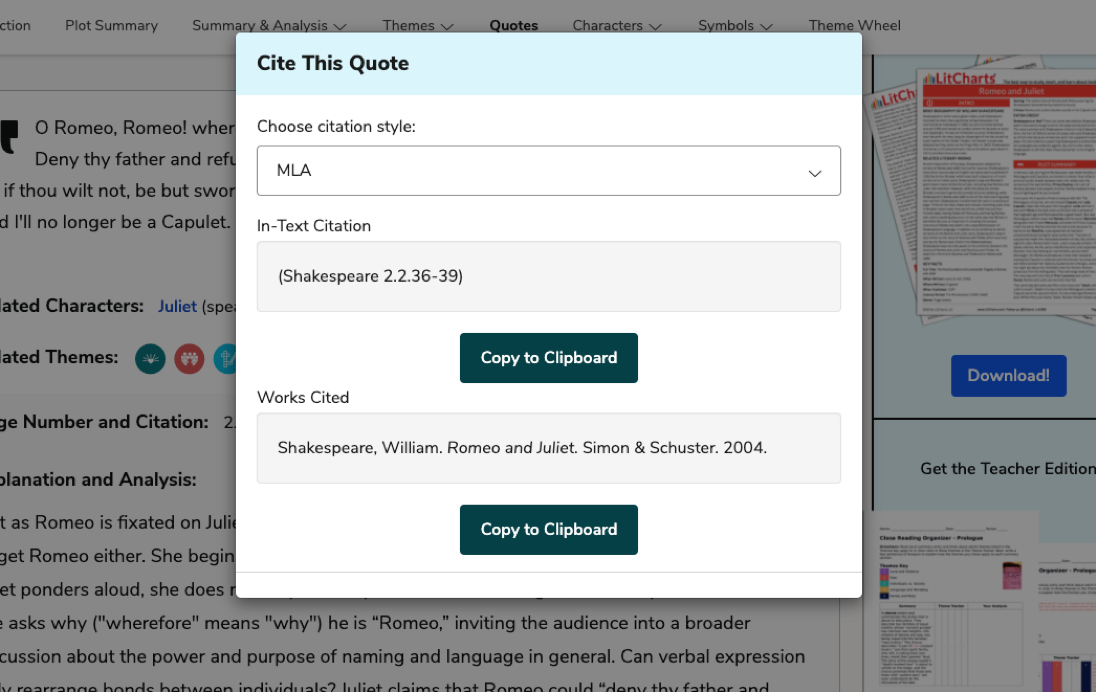

Quotes Explanations

Find the perfect quote. Understand it perfectly. Then rock the citation, too.

For all 50,101 quotes we cover.

For all 50,101 quotes we cover.

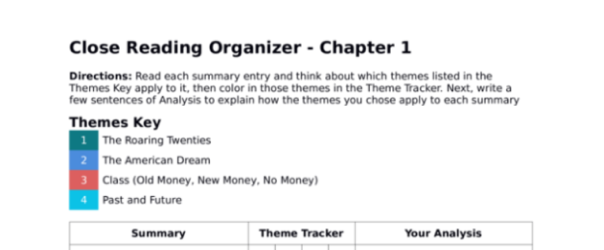

Teacher Editions

Close reading made easy for students.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

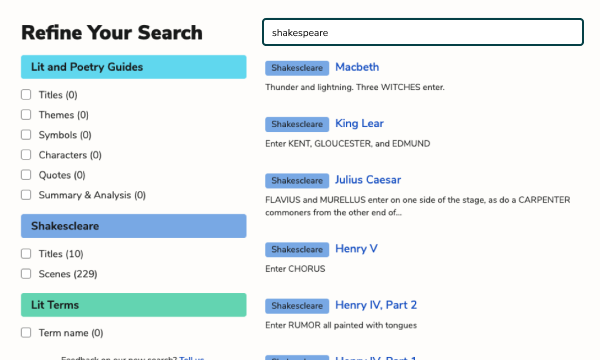

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

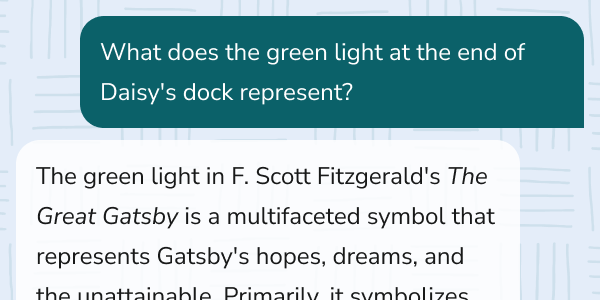

Literary Terms and Devices

Definitions and examples for every literary term and device you need to know.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Try a free sample literary term PDF.

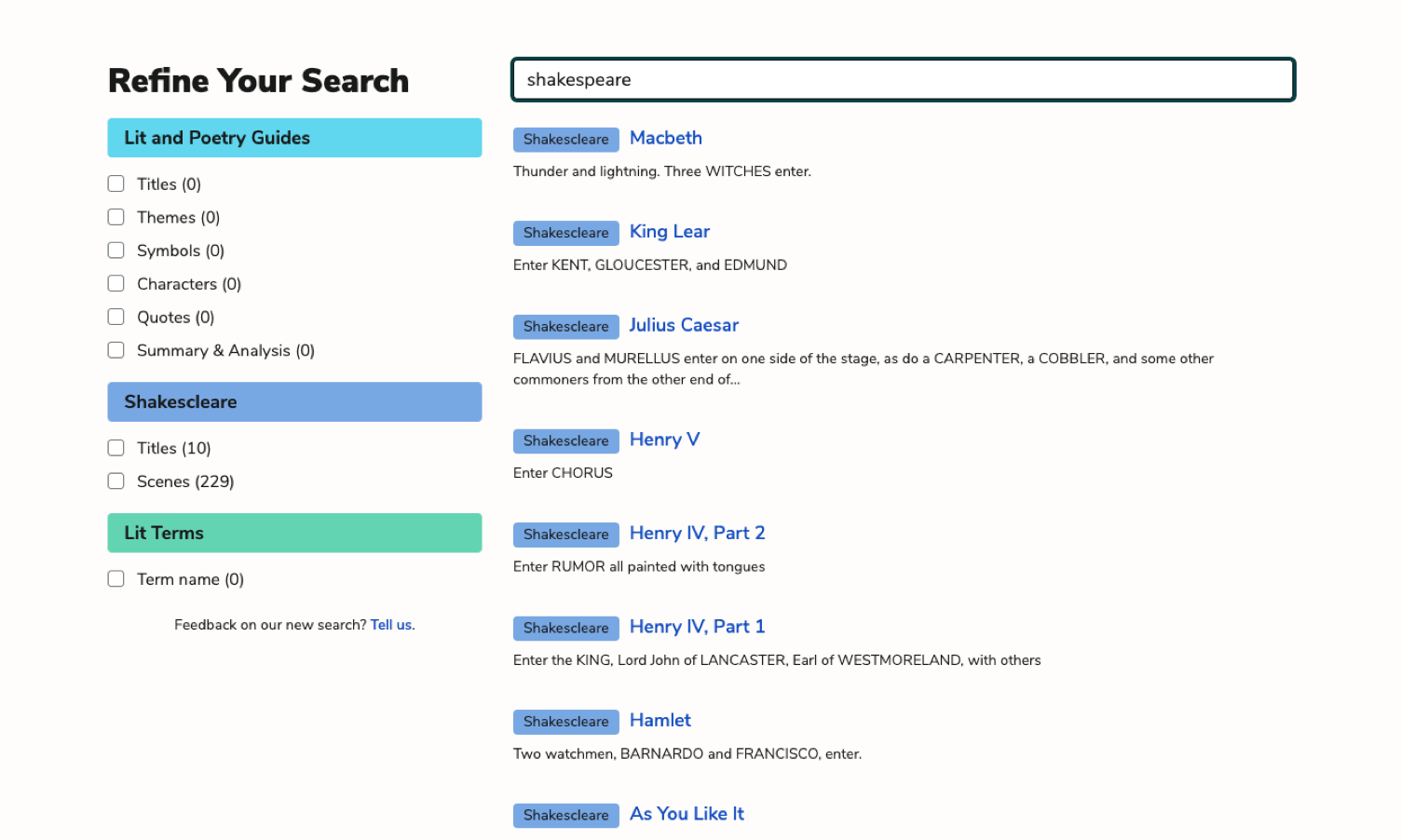

Advanced Search

Refine any search. Find related themes, quotes, symbols, characters, and more.

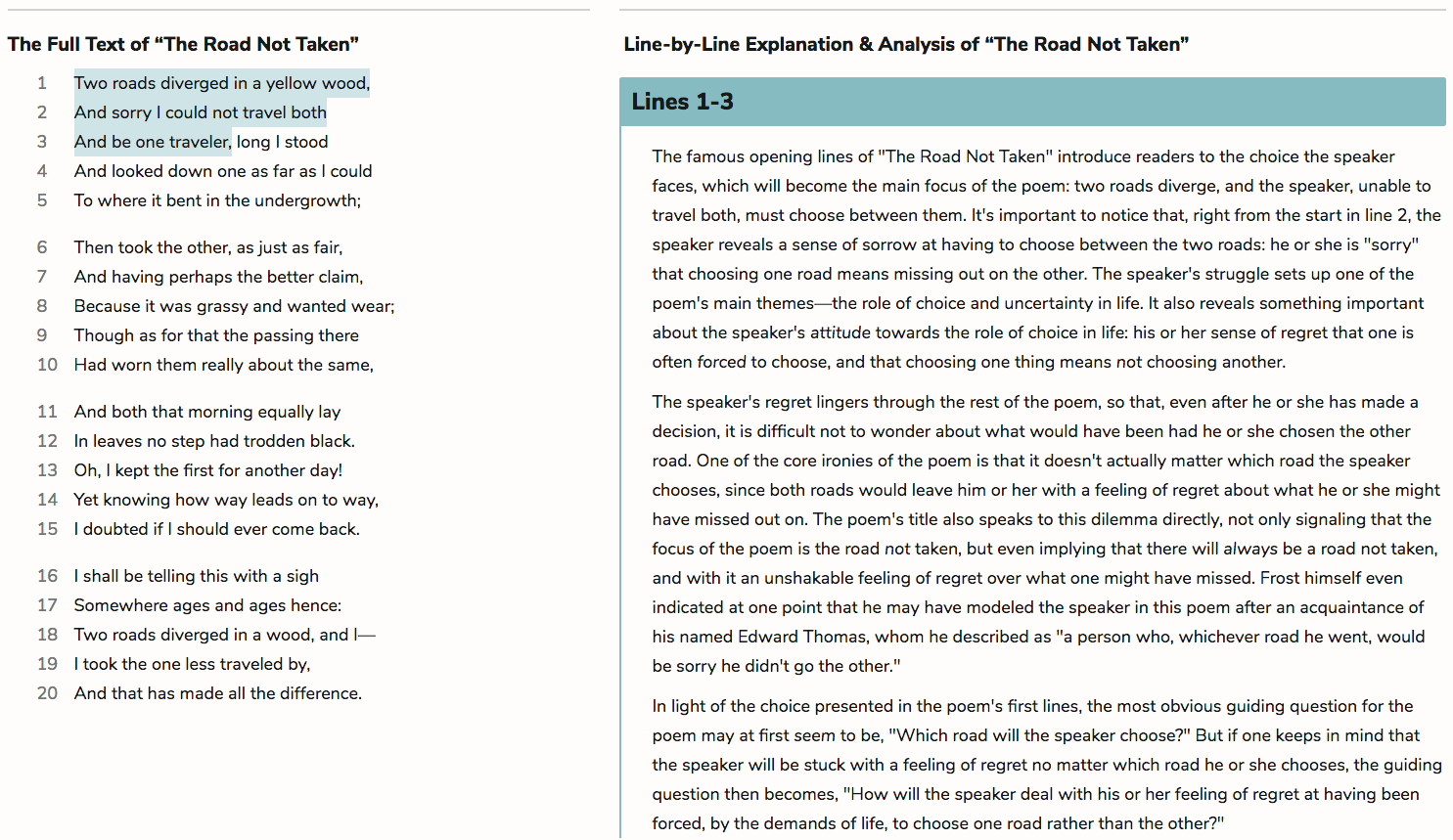

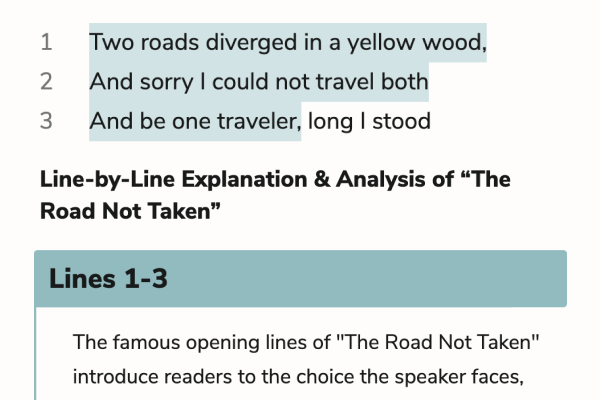

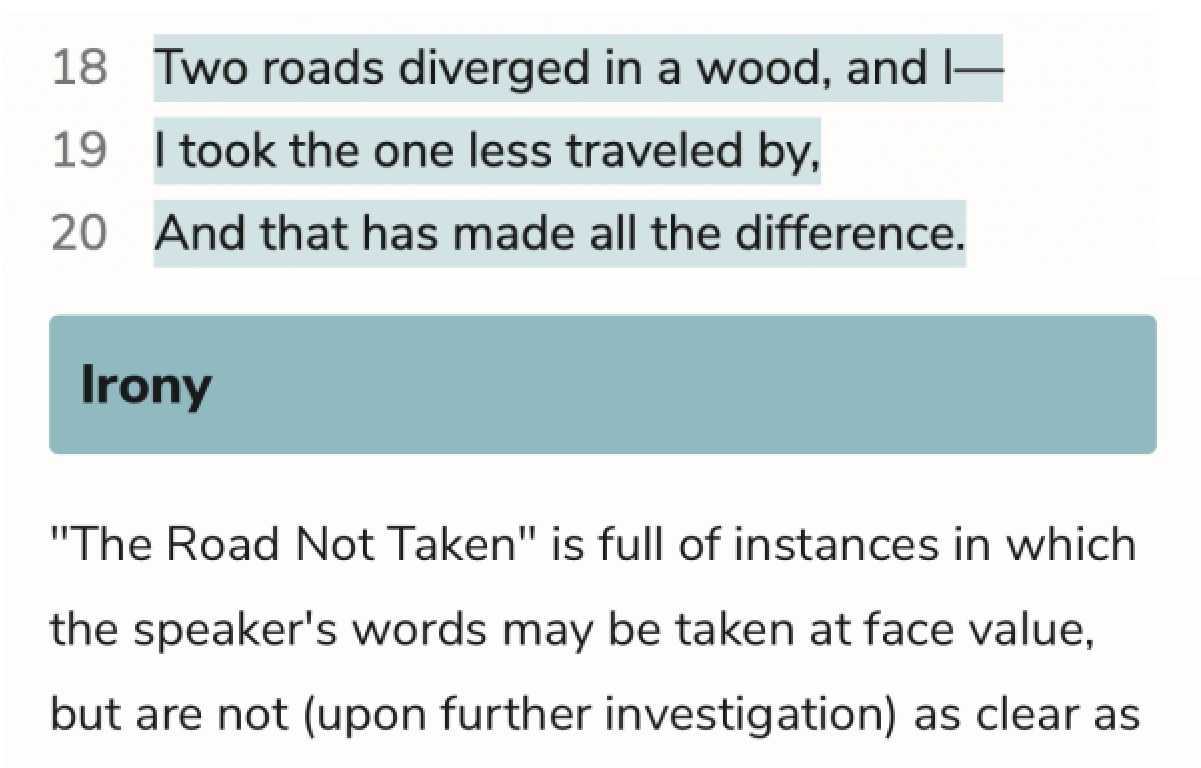

Poetry Guides

Line-by-line explanations and analysis of figurative language and poetic devices.

For every lyric poem we cover.

For every lyric poem we cover.