|

Have questions?

Contact us

Already a member? Sign in

|

Get every literary device explanation for LeviathanPlus so much more...

Sign up for LitCharts A+Get instant access to every literary device explanation, plus so much more...

Allegory

Explanation and Analysis—Assemblies:

Hobbes develops the allegory of the “body politic”—or commonwealth of the state—in his discussion of “assemblies,” or large groups of citizens who mean, by force, to compel the state to act in a certain way. He describes a biblical episode in which an assembly of people demand that the government bring two men, Christian preachers, to justice. The magistrate declares the assembly illegal, and, as Hobbes notes:

[He] calleth an Assembly, whereof men can give no just account, a Sedition, and such as they could not answer for. And this is all I shall say concerning Systemes, and Assemblyes of People, which may be compared (as I said,) to the Similar parts of mans Body; such as be Lawfull, to the Muscles; such as are Unlawfull, to Wens, Biles, and Apostemes, engendred by the unnaturall conflux of evill humours.

Hobbes is deeply opposed to the idea that groups of citizens can compete with the state for control, as for him, the power of the Sovereign and his representatives must be absolute to ensure the security of the commonwealth. As he does throughout Leviathan, he analyzes this social question through the lens of the allegorical body politic.

A lawful assembly raised by the state in order to accomplish some goal is, for Hobbes, the “Muscles” of the collective body; however, “Unlawwful” assemblies that organize against the state are figured by Hobbes as “Wens, Biles, and Apostemes”—or, in other words, various physical ailments. An angry mob, then, is an “unatural conflux of evill humours,” detrimental to the health of the body politic.

Monthly

Annual (Best Value)

$595USD/mo

Charged $71.40 USD every year

Teacher

Teacher$795USD/mo

Charged $95.40 USD every year

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Instant PDF downloads of all 2247 LitCharts literature guides and of every new one we publish. Try a free sample literature guide.

"Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!"

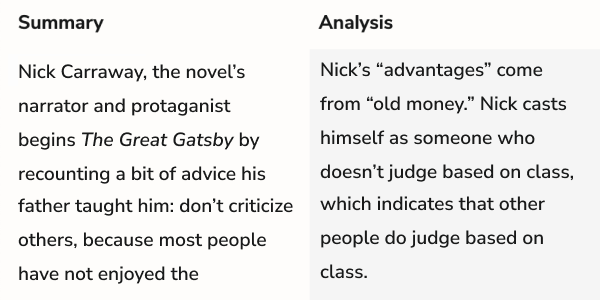

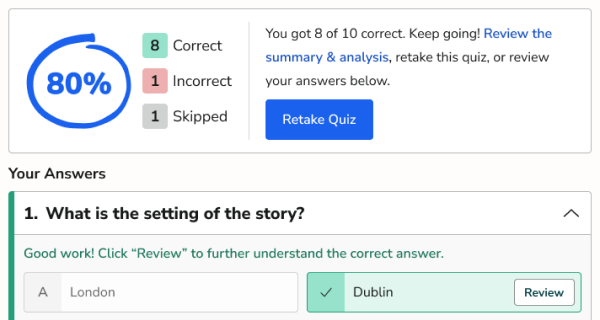

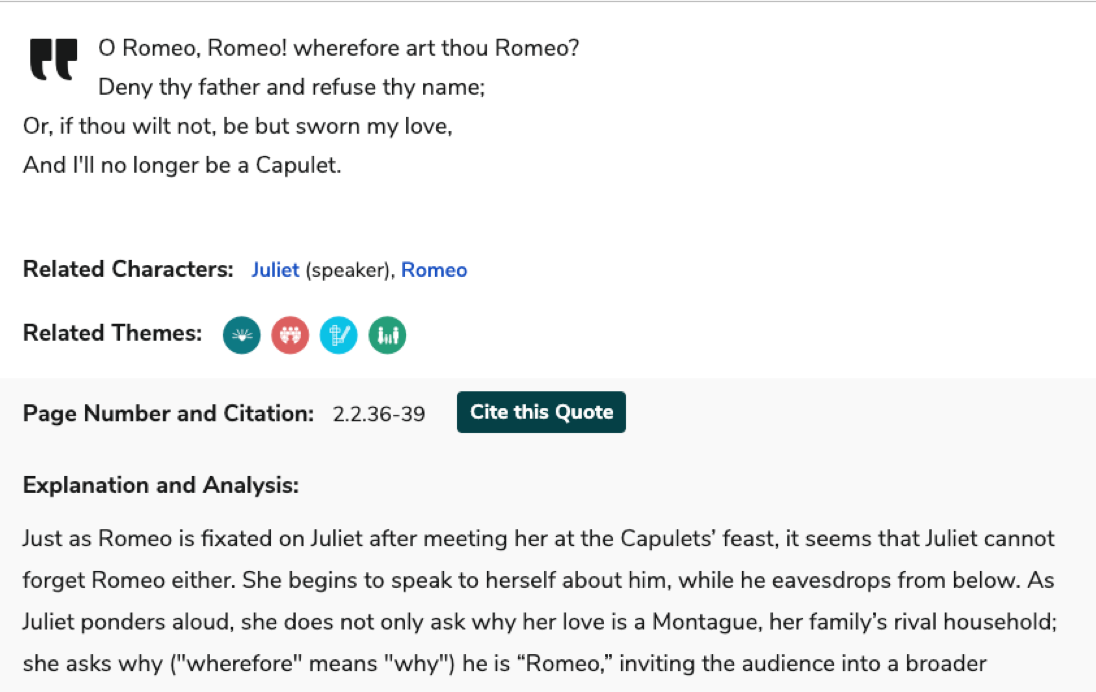

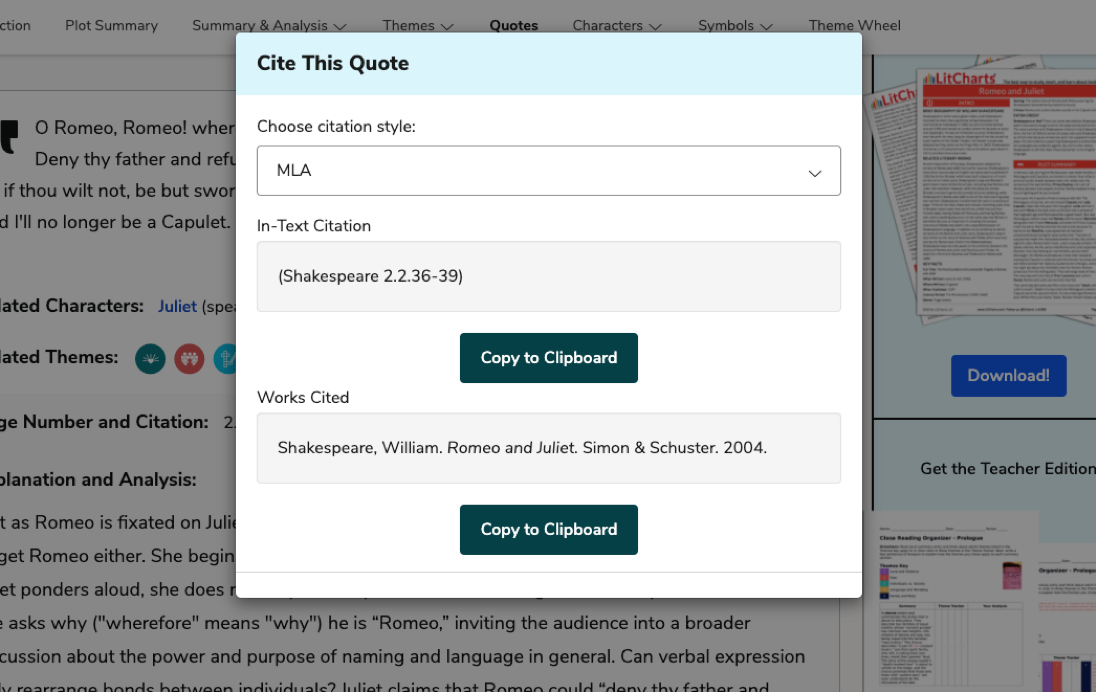

Quotes Explanations

Find the perfect quote. Understand it perfectly. Then rock the citation, too.

For all 50,101 quotes we cover.

For all 50,101 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

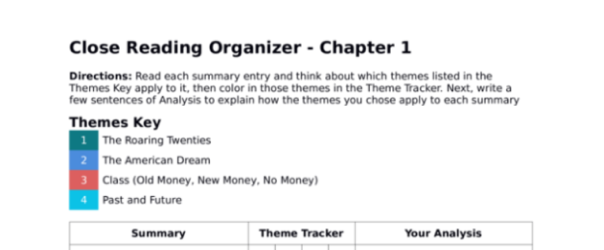

Close reading made easy for students.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

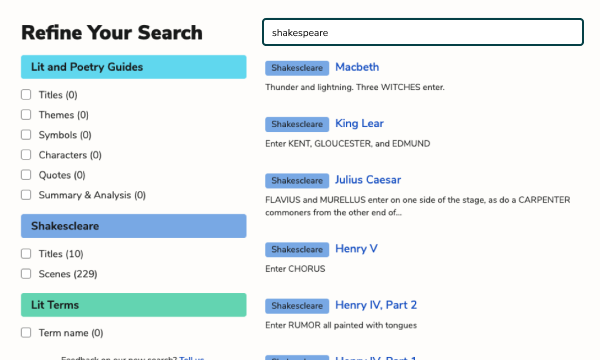

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

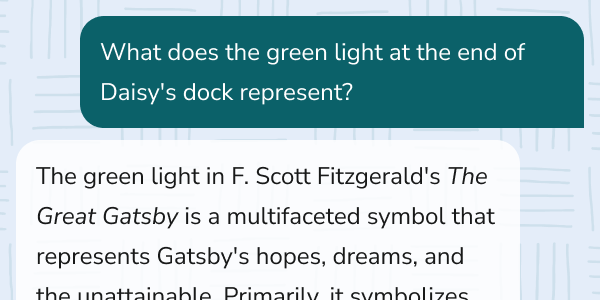

Literary Terms and Devices

Definitions and examples for every literary term and device you need to know.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Try a free sample literary term PDF.

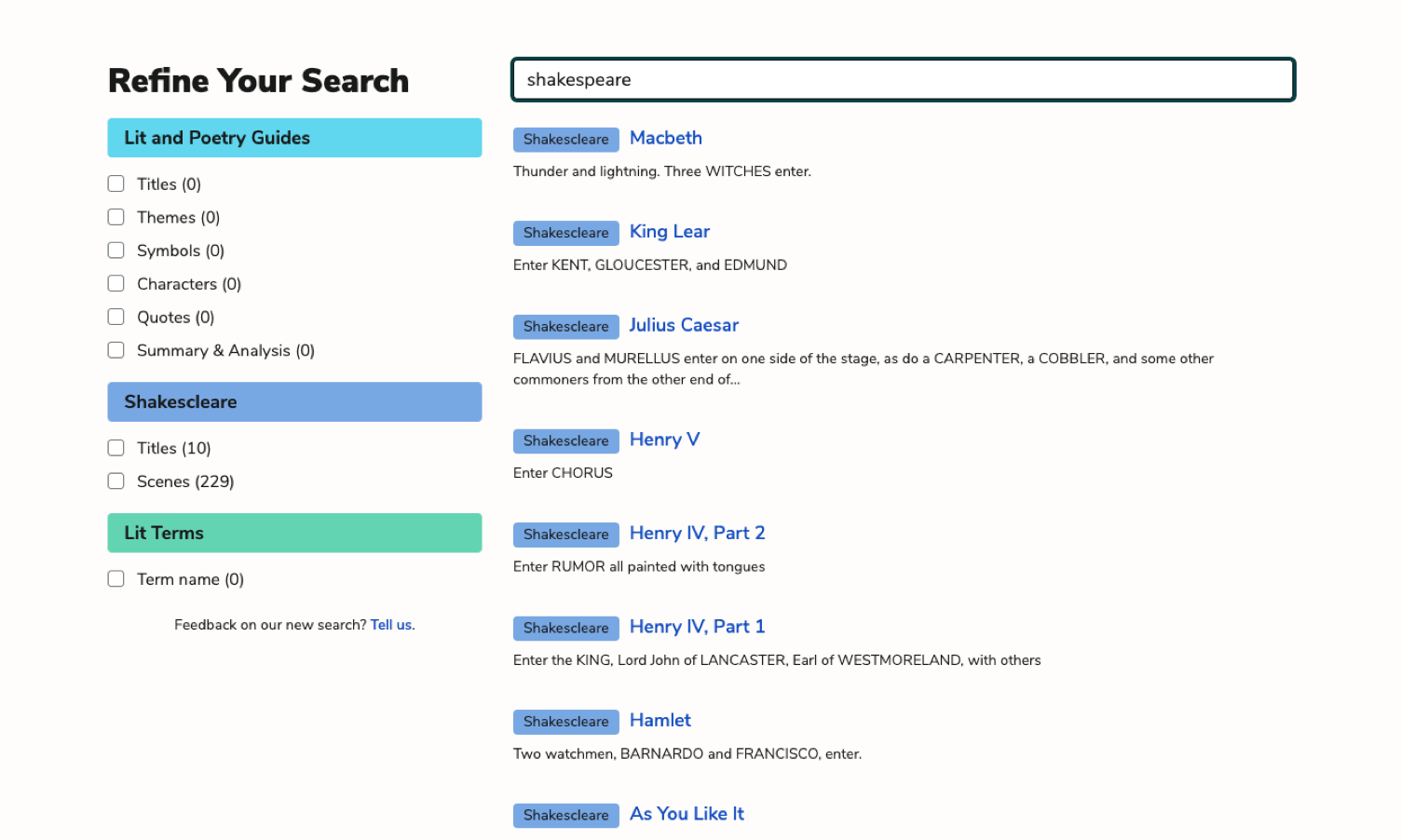

Advanced Search

Refine any search. Find related themes, quotes, symbols, characters, and more.

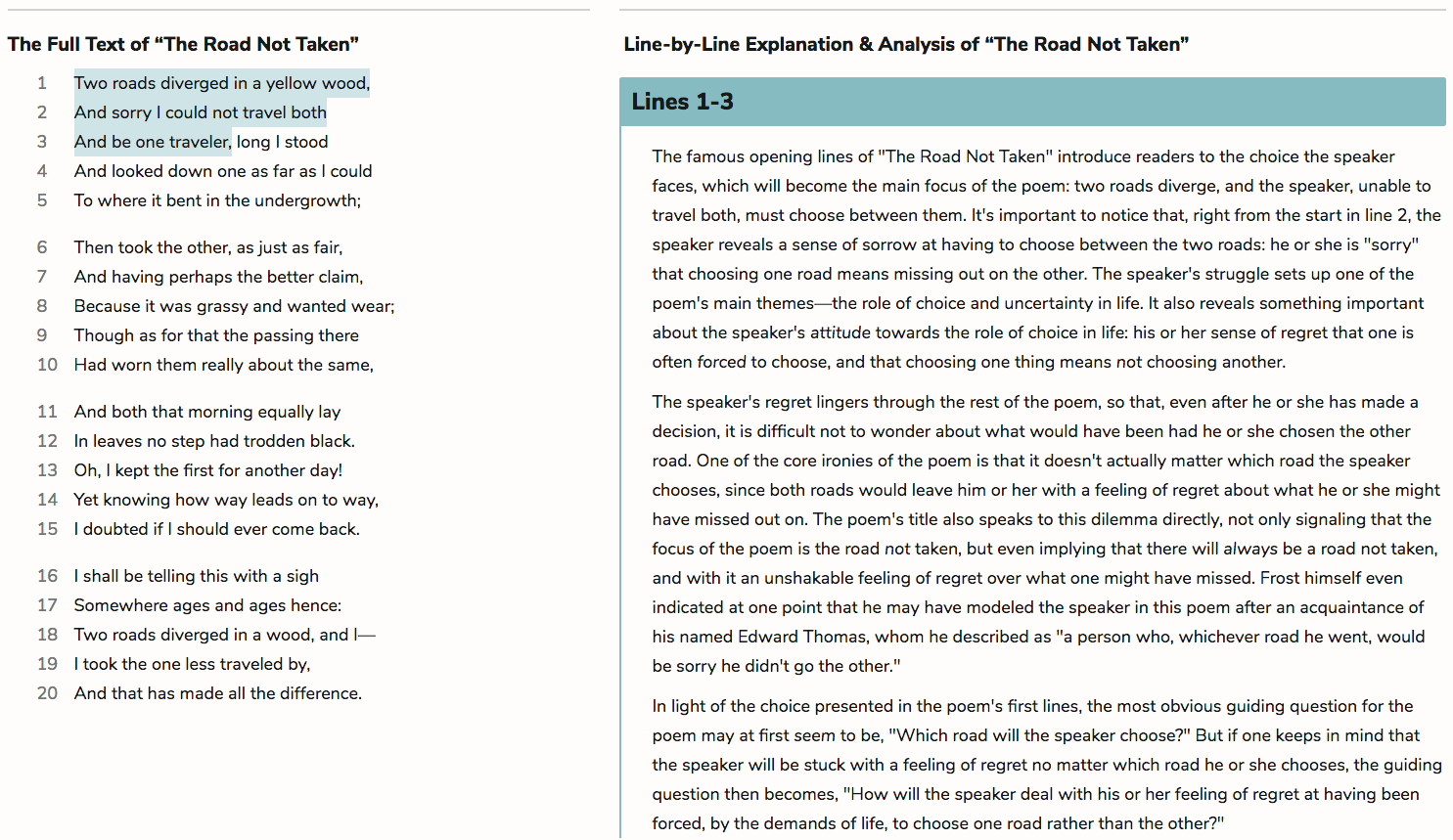

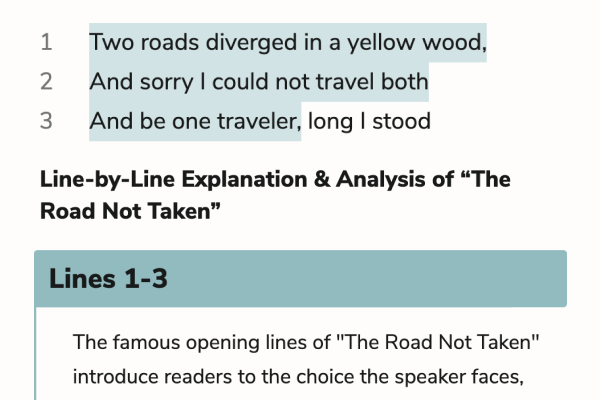

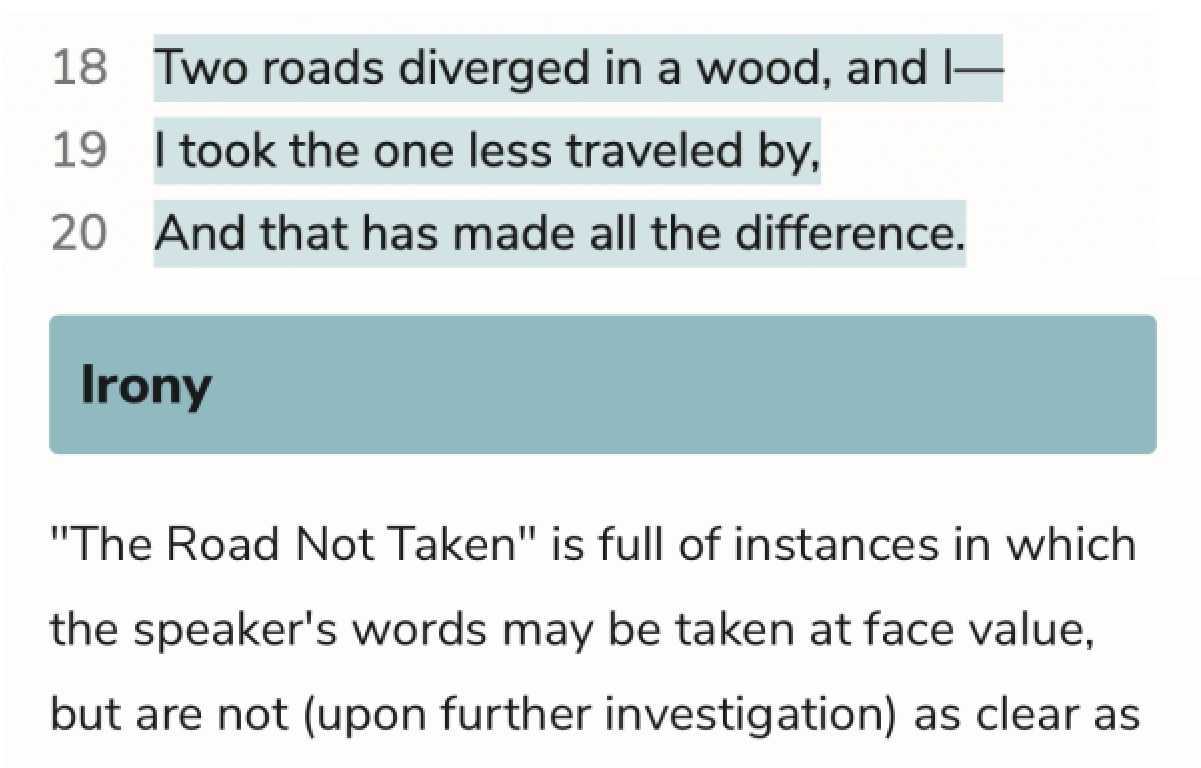

Poetry Guides

Line-by-line explanations and analysis of figurative language and poetic devices.

For every lyric poem we cover.

For every lyric poem we cover.