|

Have questions?

Contact us

Already a member? Sign in

|

Get every literary device explanation for The Adventures of Tom SawyerPlus so much more...

Sign up for LitCharts A+Get instant access to every literary device explanation, plus so much more...

Allusion

Explanation and Analysis—Robin Hood:

At a few points in the novel, Tom encourages his friends to “play Robin Hood” with him, an allusion to the English folktale about an outlaw named Robin Hood who stole from the rich to give to the poor. Here, Tom asks Huck if he knows about Robin Hood before they start their fantasy games:

“Do you know Robin Hood, Huck?”

“No. Who’s Robin Hood?”

“Why, he was one of the greatest men that was ever in England—and the best. He was a robber.”

“Cracky, I wisht I was. Who did he rob?”

“Only sheriffs and bishops and rich people and kings, and such like. But he never bothered the poor. He loved ‘em. He always divided up with ’em perfectly square.”

“Well, he must ‘a’ been a brick.”

“I bet you he was, Huck. Oh, he was the noblest man that ever was. They ain’t any such men now, I can tell you.”

Tom’s love of Robin Hood is about adventure, of course—the way he idealizes Robin Hood’s thievery makes that clear—but it is also about morality. As Tom explains to Huck, Robin Hood cared about the poor and was “the noblest man that ever was.” That Tom believes there “ain’t any such men now” is Twain’s way of indicating that Tom notices the hypocrisy of the men around him—Mr. Dobbins, for example, abuses his power as a teacher by punishing children, and Mr. Walters the Sunday School superintendent cares more about getting in good Judge Thatcher’s graces than sticking to his principles.

Tom, on the other hand, earnestly wants to help those with less power. Despite his manipulative ways, he would never wield power against anyone in order to hurt them, as he proves over the course of the novel. Twain’s allusions to Robin Hood may also be a way of articulating his own allegiance—he is writing a novel centered on average people closer to being poor than being rich, after all (which is what makes his story a realist one rather than a romantic one).

Monthly

Annual (Best Value)

$595USD/mo

Charged $71.40 USD every year

Teacher

Teacher$795USD/mo

Charged $95.40 USD every year

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Instant PDF downloads of all 2247 LitCharts literature guides and of every new one we publish. Try a free sample literature guide.

"Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!"

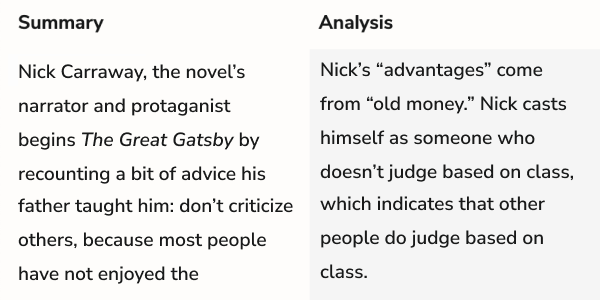

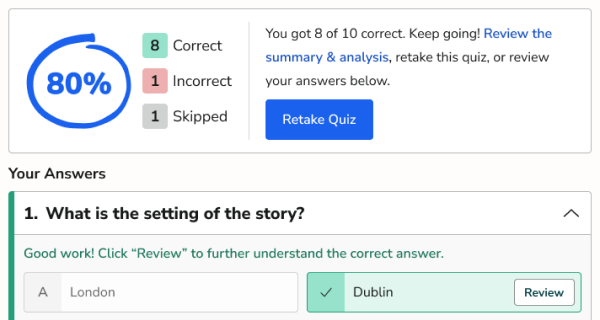

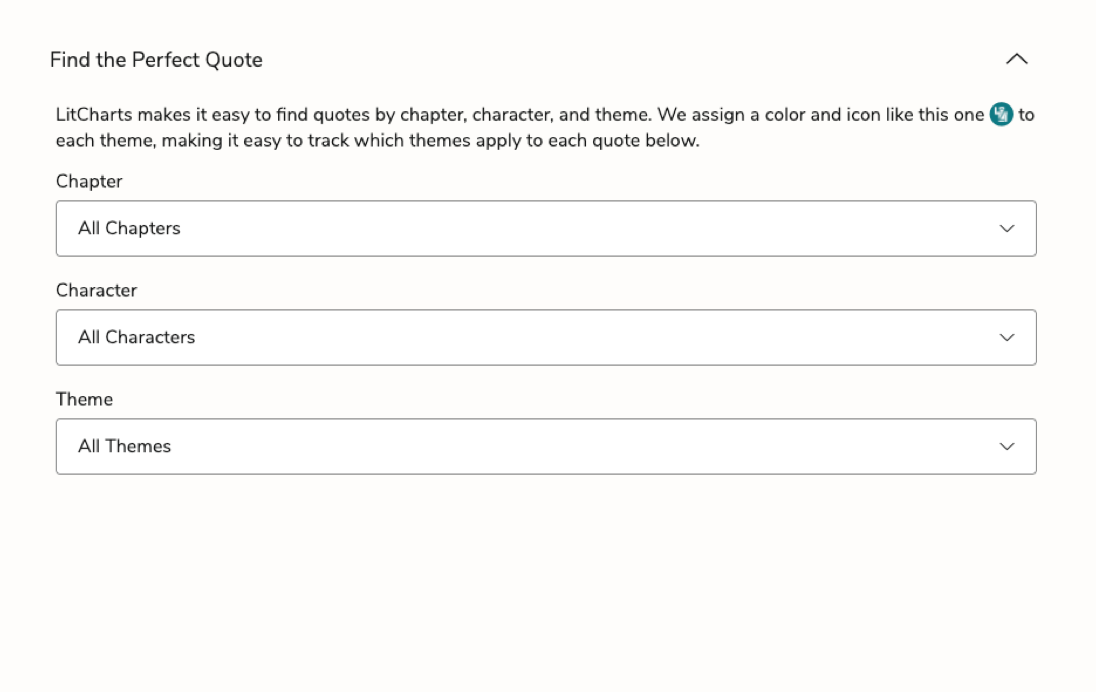

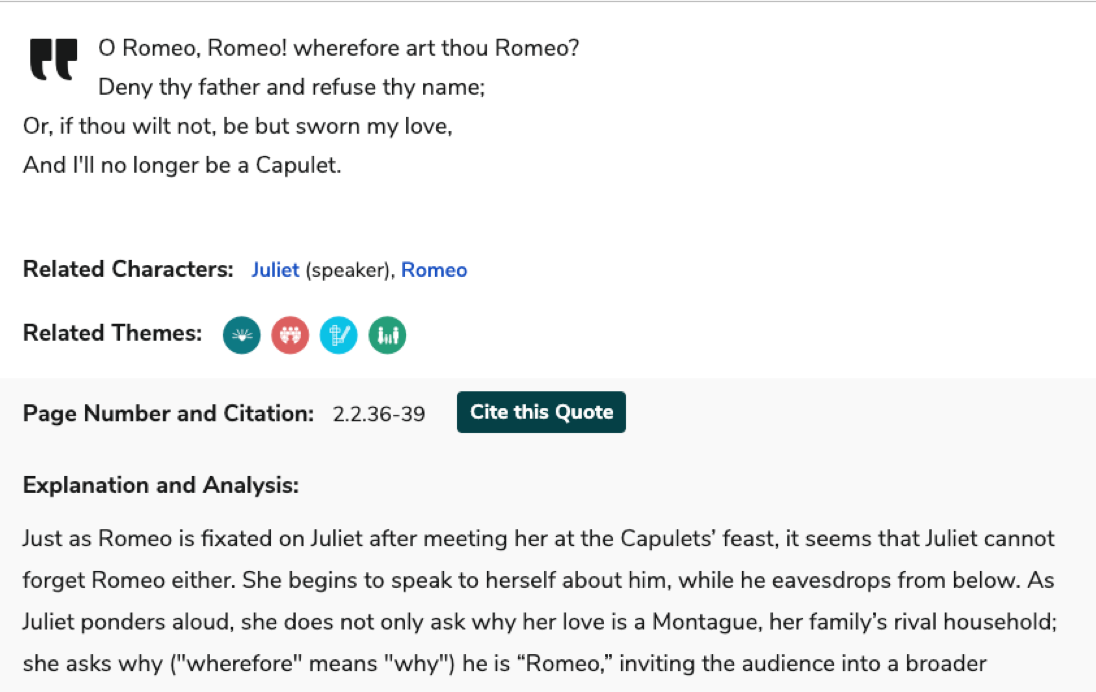

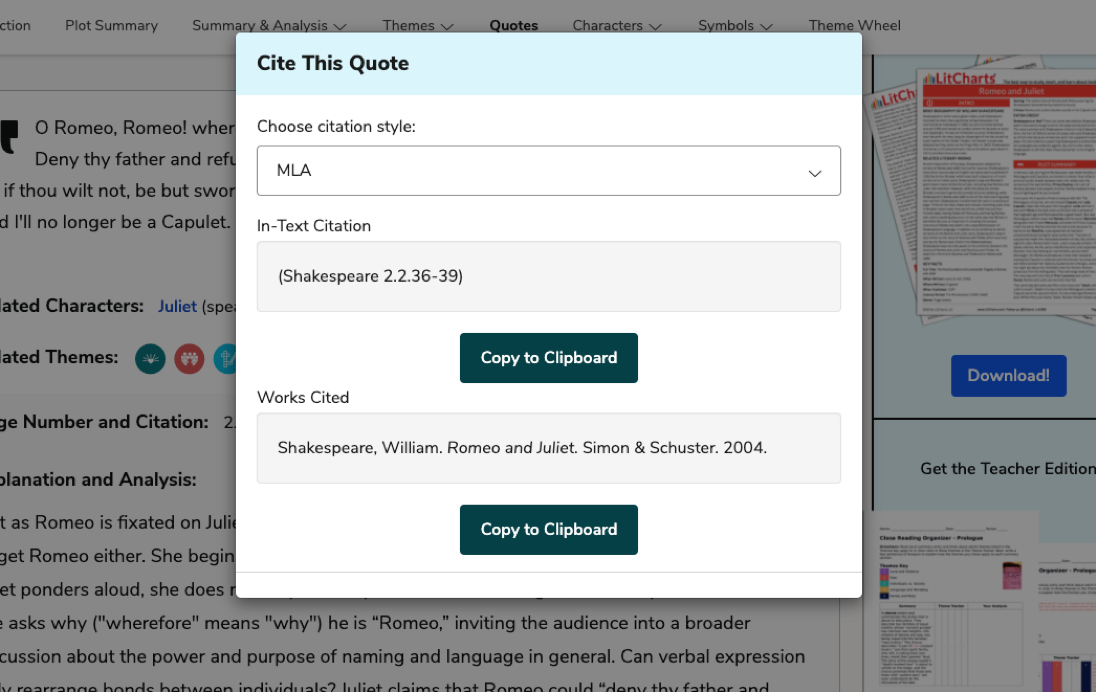

Quotes Explanations

Find the perfect quote. Understand it perfectly. Then rock the citation, too.

For all 50,101 quotes we cover.

For all 50,101 quotes we cover.

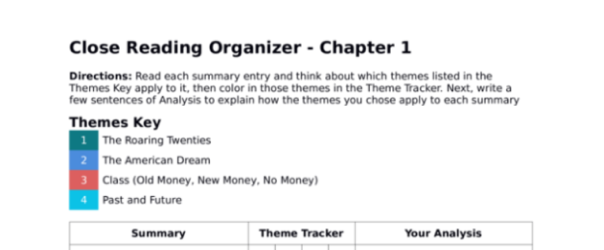

Teacher Editions

Close reading made easy for students.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

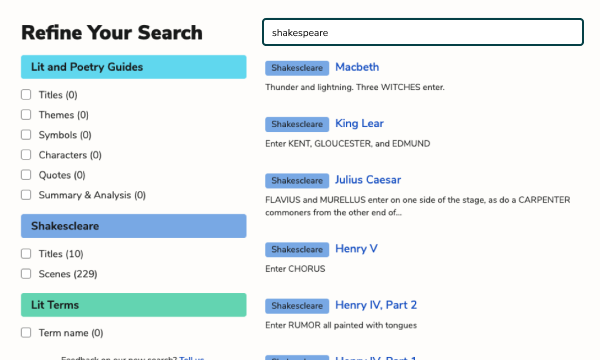

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

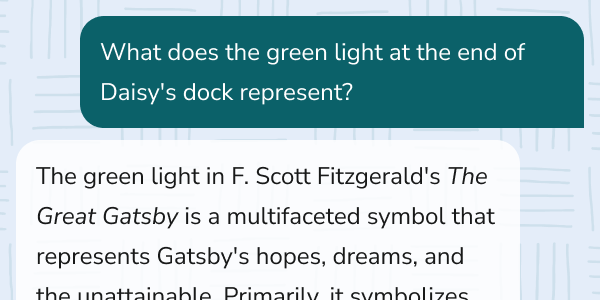

Literary Terms and Devices

Definitions and examples for every literary term and device you need to know.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Try a free sample literary term PDF.

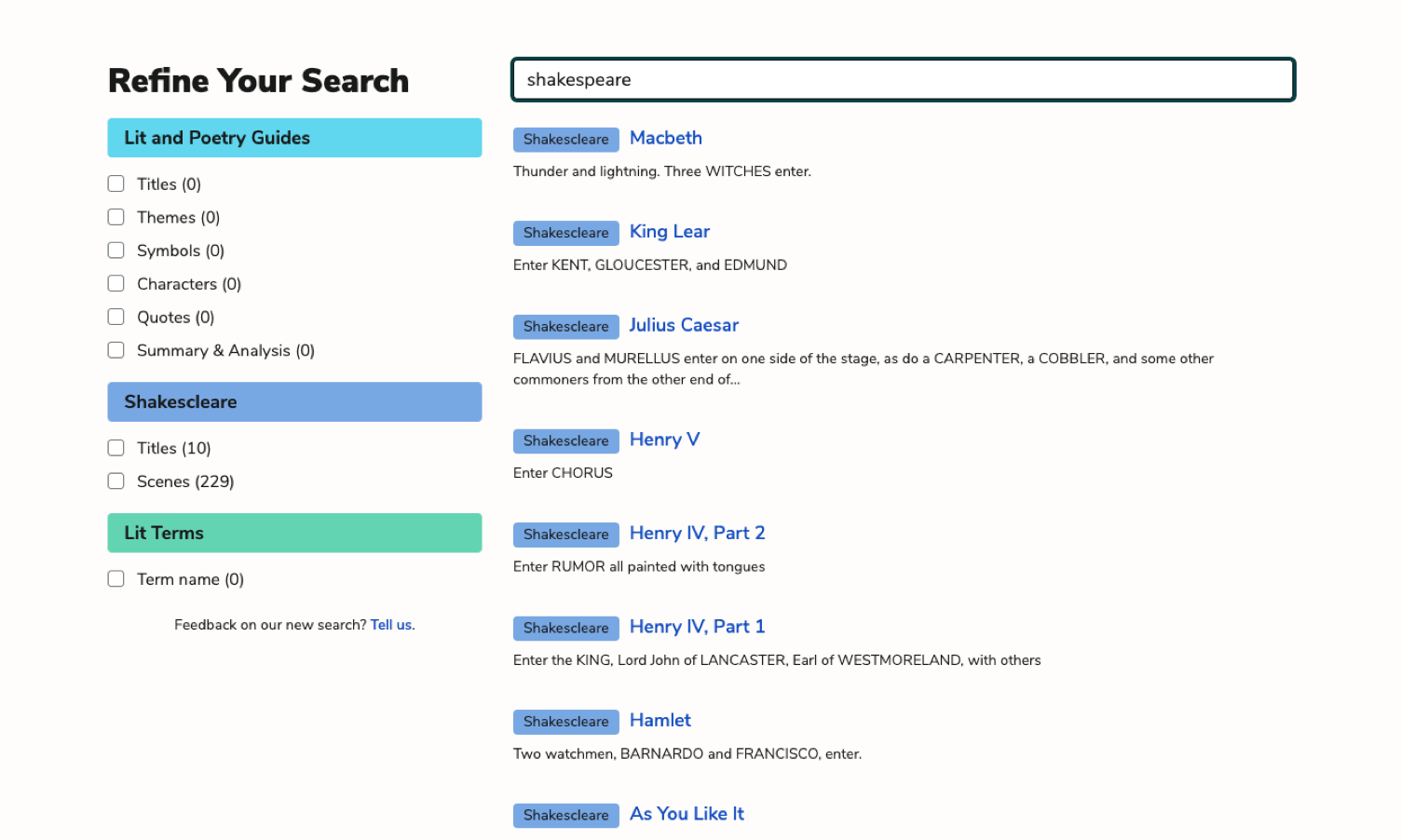

Advanced Search

Refine any search. Find related themes, quotes, symbols, characters, and more.

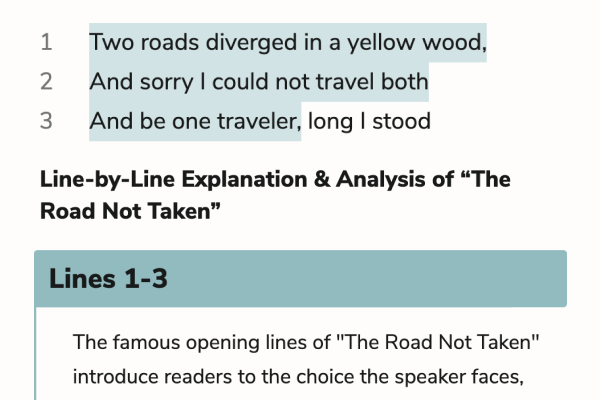

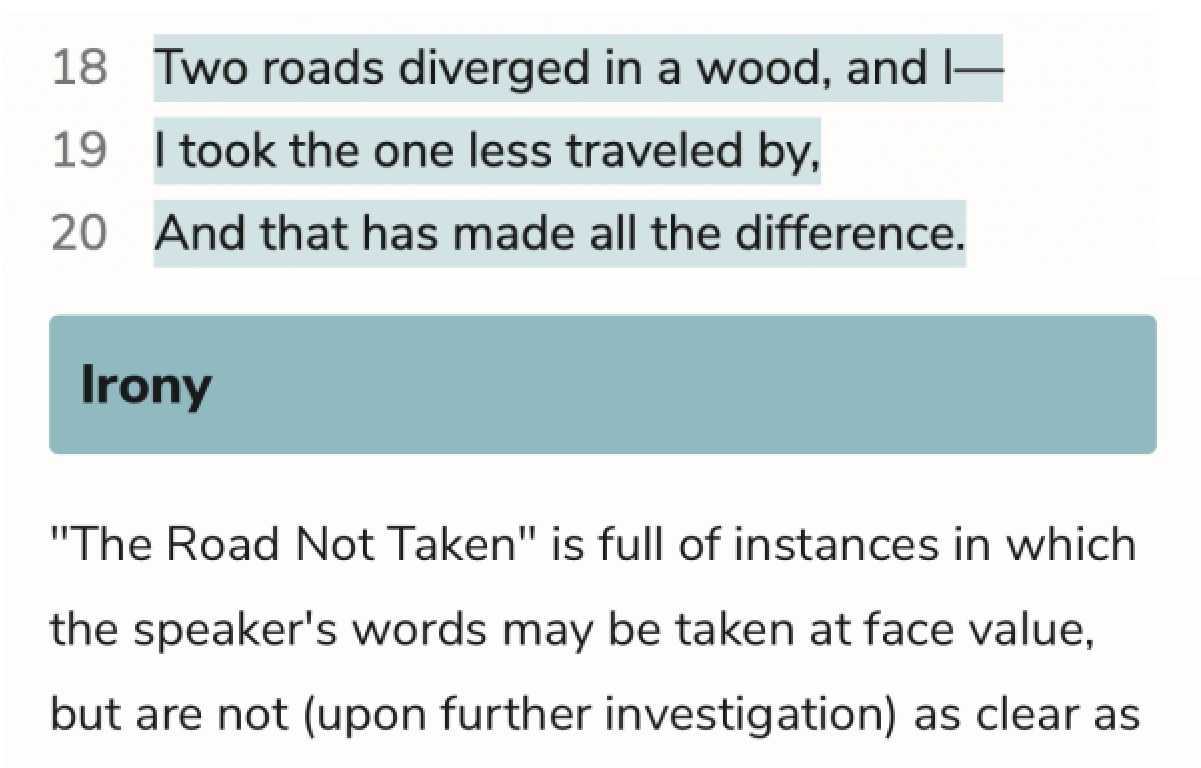

Poetry Guides

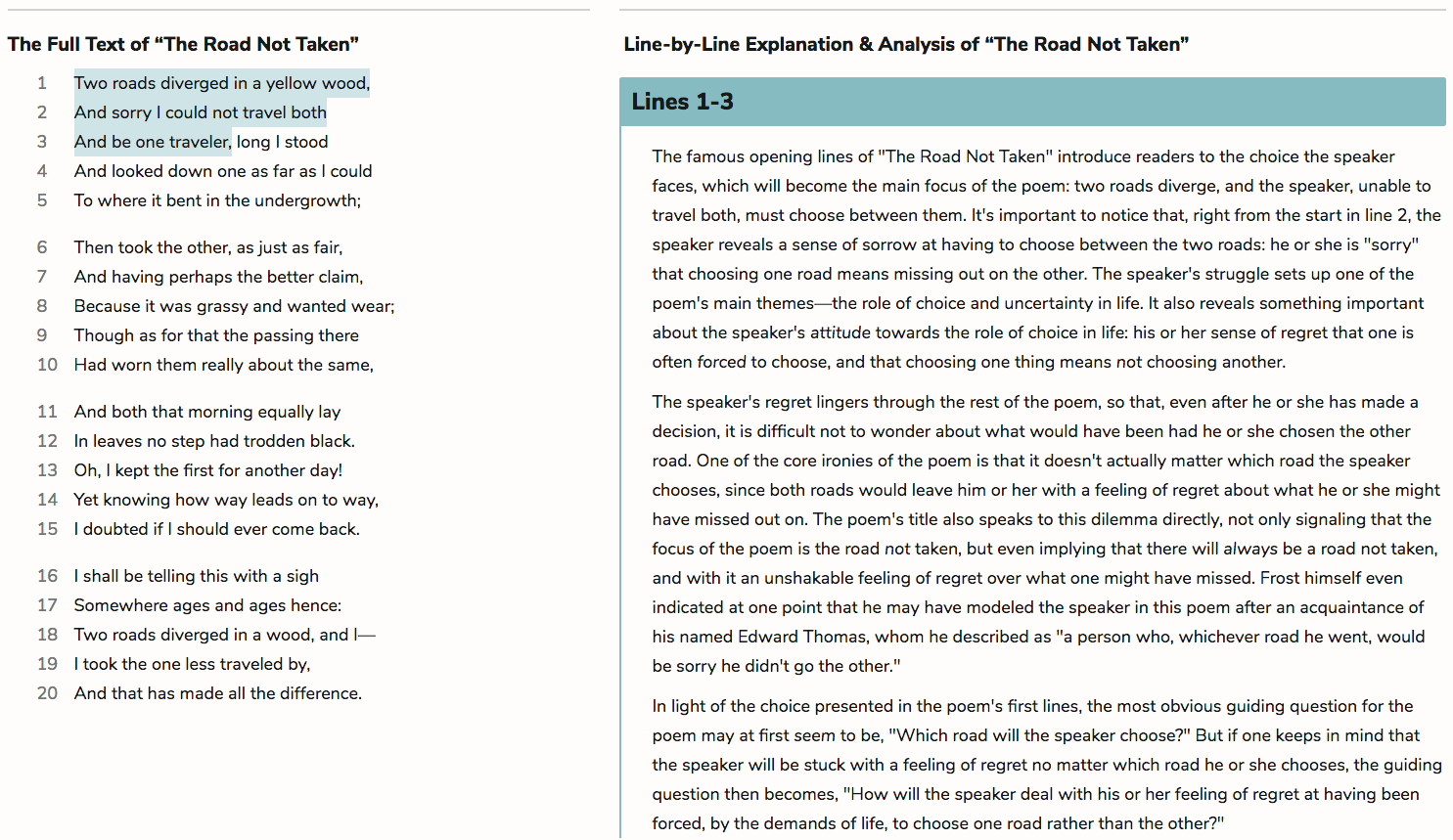

Line-by-line explanations and analysis of figurative language and poetic devices.

For every lyric poem we cover.

For every lyric poem we cover.