|

Have questions?

Contact us

Already a member? Sign in

|

Get every literary device explanation for Bleak HousePlus so much more...

Sign up for LitCharts A+Get instant access to every literary device explanation, plus so much more...

Imagery

Explanation and Analysis—Repeated Images:

When Dickens describes London, a great deal of his language at the beginning of the novel emphasizes its endless, repetitive streets and impenetrable, gloomy weather. It's worst, it seems, where the London legal system makes its home, as Dickens tells the reader in Chapter 1:

Gas looming through the fog in divers places in the streets, much as the sun may, from the spongey fields, be seen to loom by husbandman and ploughboy. Most of the shops lighted two hours before their time [...]

The raw afternoon is rawest, and the dense fog is densest, and the muddy streets are muddiest, near that leaden-headed old obstruction, appropriate ornament for the threshold of a leaden-headed old corporation: Temple Bar. And hard by Temple Bar, in Lincoln’s Inn Hall, at the very heart of the fog, sits the Lord High Chancellor in his High Court of Chancery.

Everything is "raw," "dense," and "muddy" in London, but it's all much rawer, denser, and muddier near the "leaden-headed" old corporation of the High Court. These dense visual images of obscurity suggest that the mystifying "fog" emanates from the Inns of Court; Dickens later makes it clear that in Bleak House, this is symbolically if not literally true.

The visual image Dickens provides here of the Lord Chancellor is like a spider in the middle of a misty web. He is right in the middle of the "leaden-headed old corporation," as if he is himself the highest concentration somehow of this "obscurity." Dickens repeats the phrase "at the very heart of the fog" later in the same chapter, as he describes the Chancellor's seat within the Courtroom itself as "right in the midst of the mud, and at the very heart of the fog." Dickens's repetition of the visual imagery of obscurity cements the idea that Chancery is grim, gloomy, and incomprehensible. The Inns of Court are so present in the lives of all the characters of Bleak House, but their inner workings and their true purpose are deliberately hazy.

Monthly

Annual (Best Value)

$595USD/mo

Charged $71.40 USD every year

Teacher

Teacher$795USD/mo

Charged $95.40 USD every year

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Instant PDF downloads of all 2251 LitCharts literature guides and of every new one we publish. Try a free sample literature guide.

"Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!"

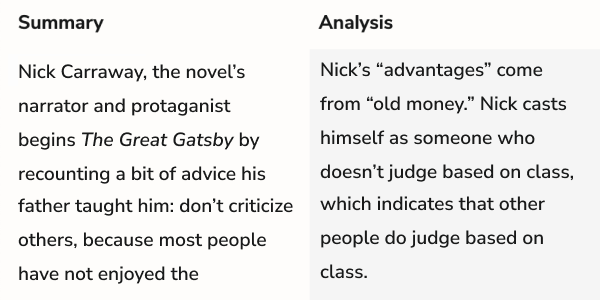

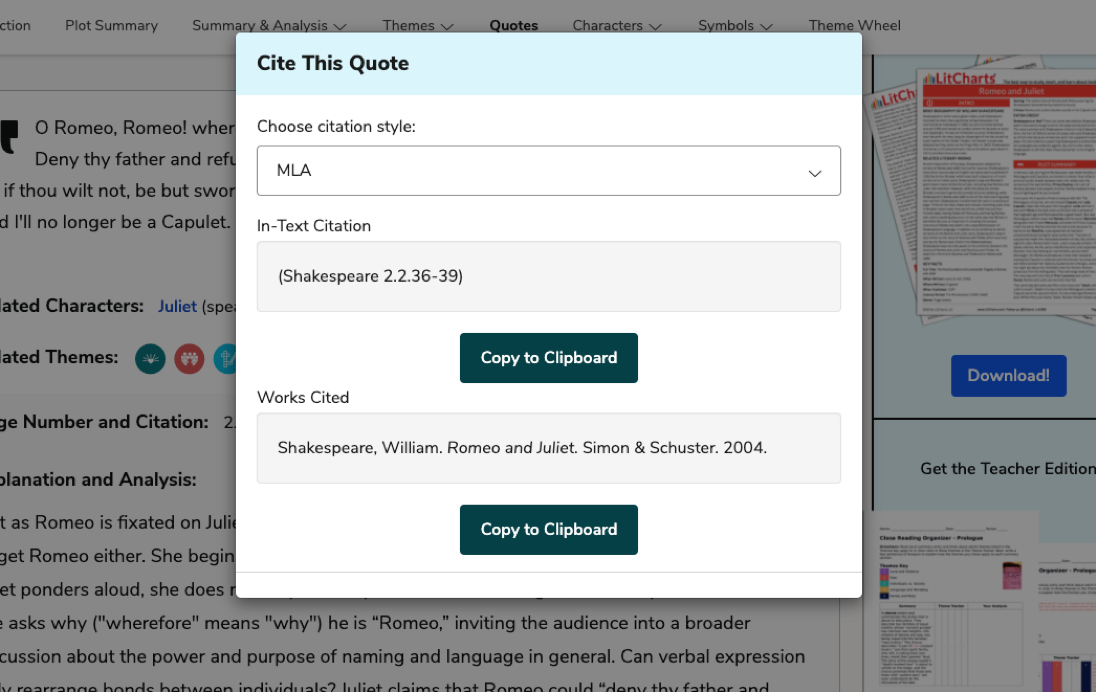

Quotes Explanations

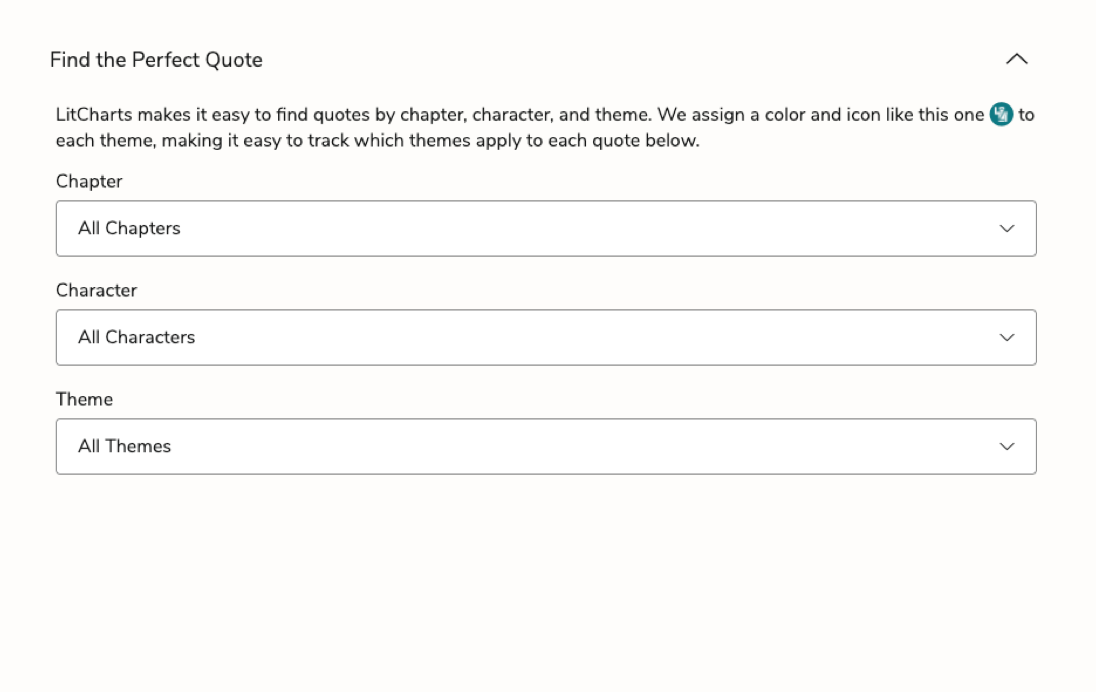

Find the perfect quote. Understand it perfectly. Then rock the citation, too.

For all 50,202 quotes we cover.

For all 50,202 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

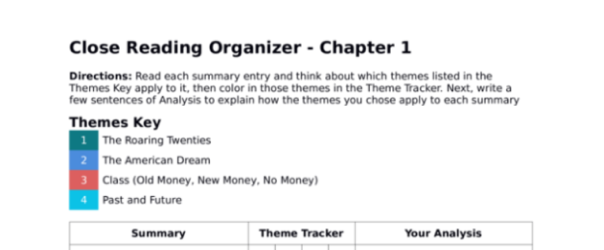

Close reading made easy for students.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

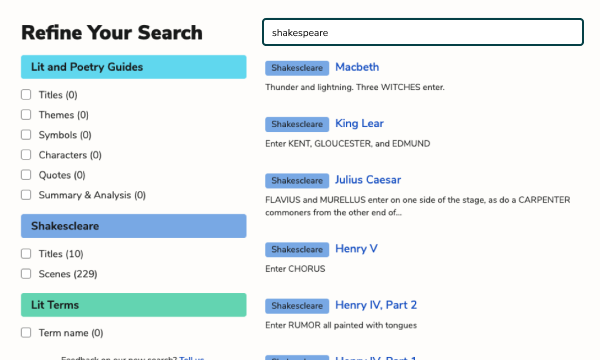

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

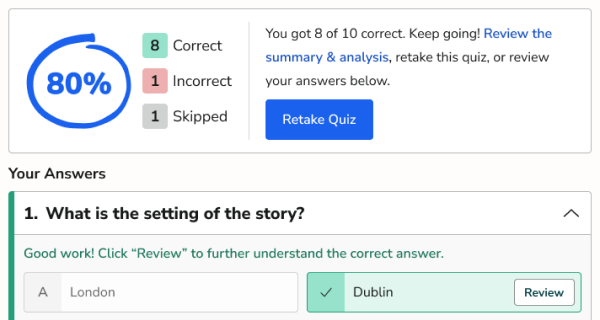

Literary Terms and Devices

Definitions and examples for every literary term and device you need to know.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Try a free sample literary term PDF.

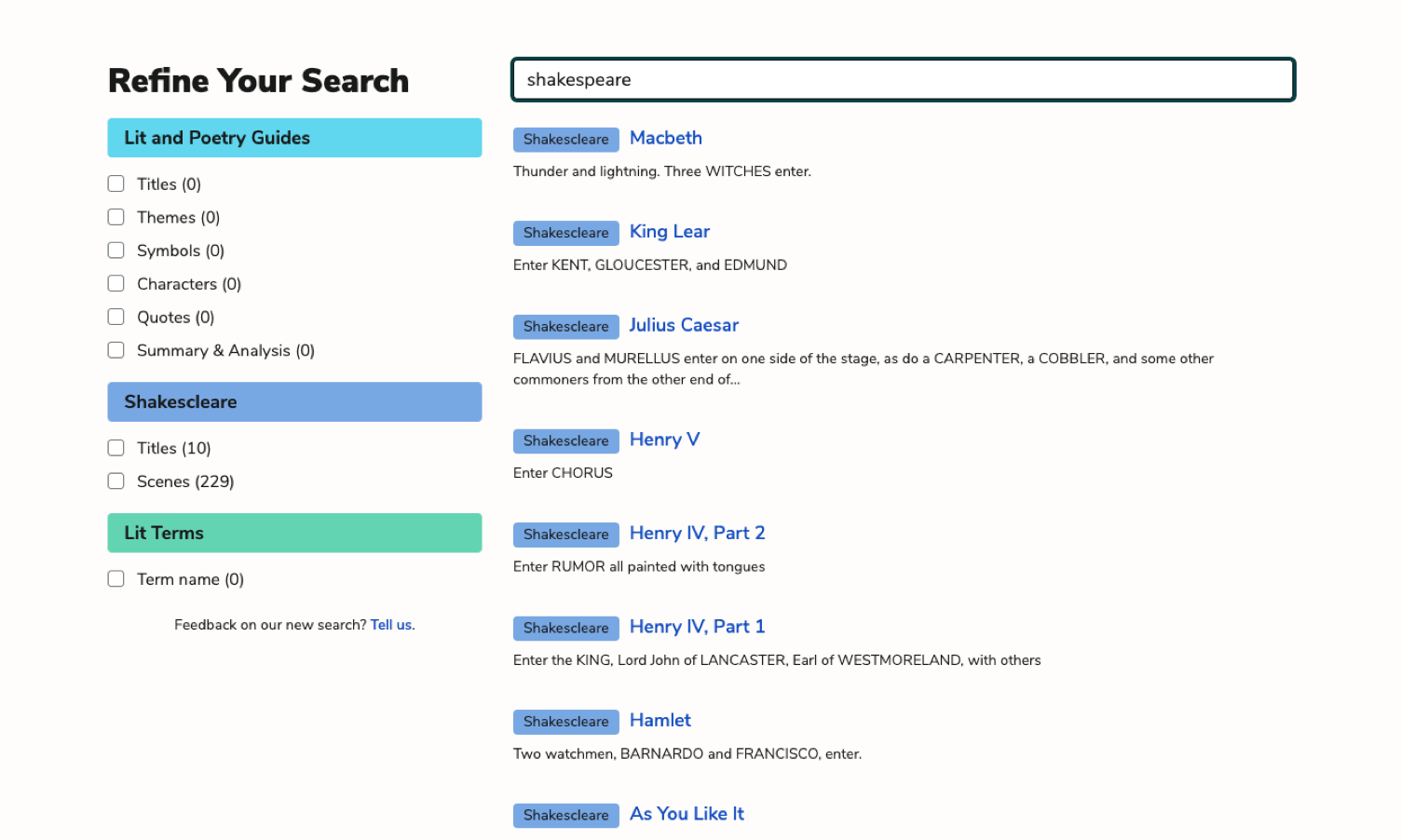

Advanced Search

Refine any search. Find related themes, quotes, symbols, characters, and more.

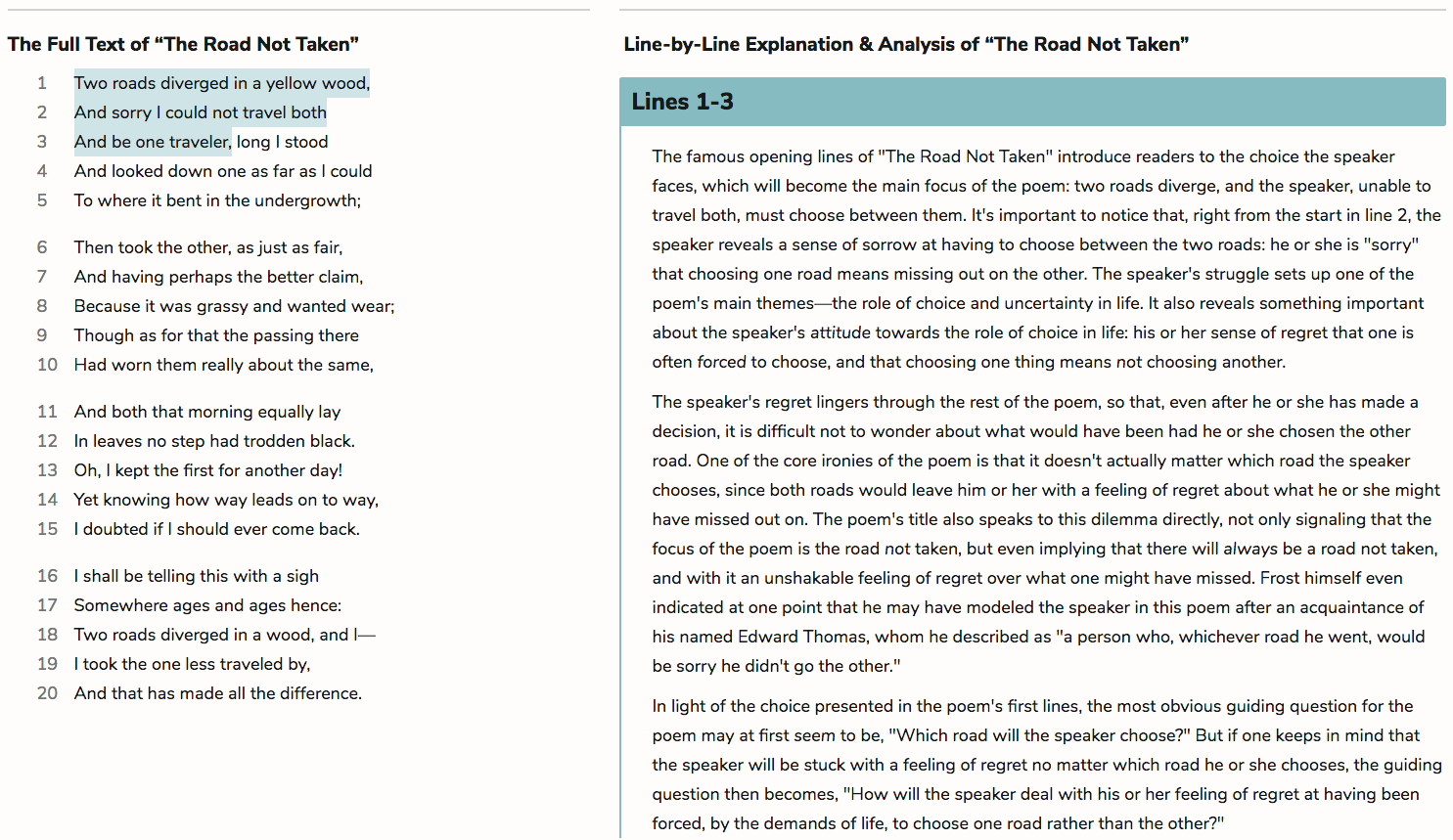

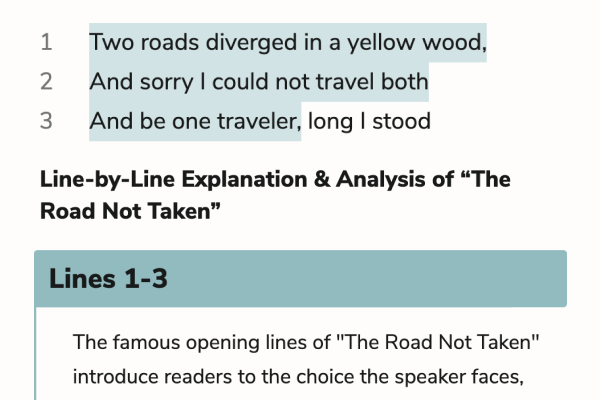

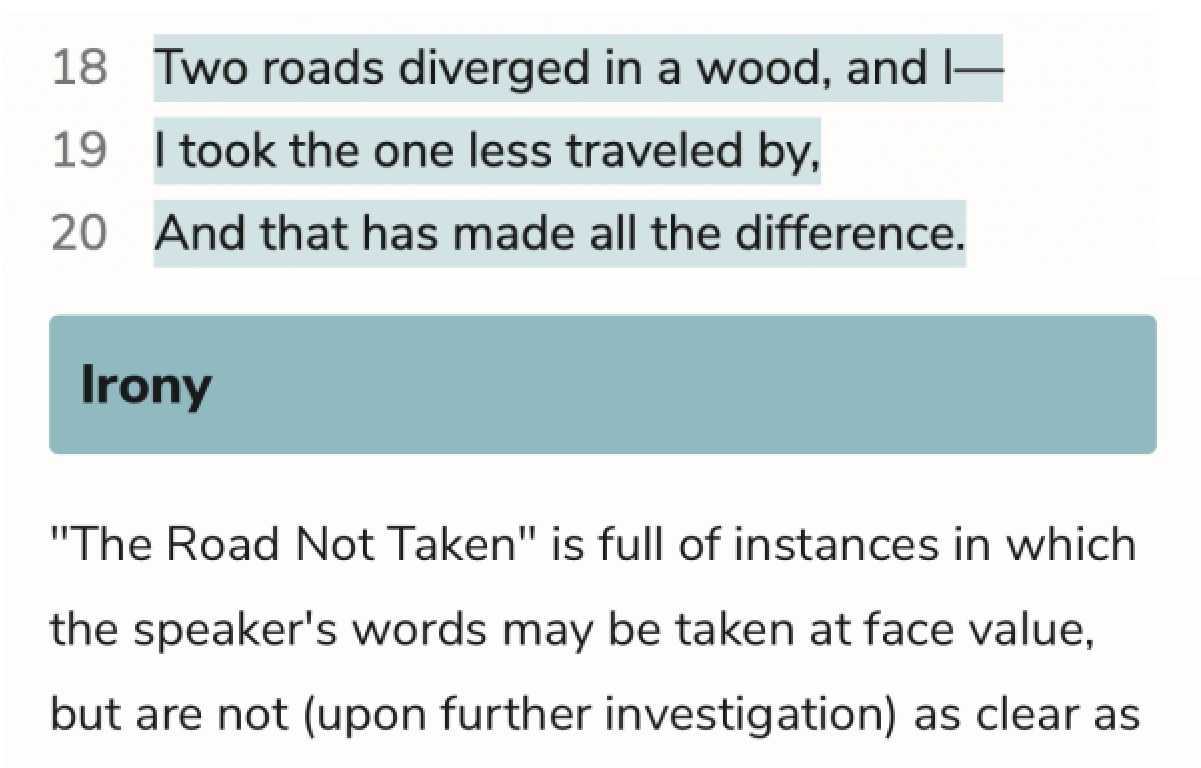

Poetry Guides

Line-by-line explanations and analysis of figurative language and poetic devices.

For every lyric poem we cover.

For every lyric poem we cover.