|

Have questions?

Contact us

Already a member? Sign in

|

Get every literary device explanation for Bleak HousePlus so much more...

Sign up for LitCharts A+Get instant access to every literary device explanation, plus so much more...

Imagery

Explanation and Analysis—Decaying Holborn:

In comparison to the wealthy, clean, and safe locations in the book, a great deal of the district of Holborn is described using the sensory language of dirt and neglect. Readers feel the grimy, unclean, and unsafe nature of the houses of Tom-All-Alone's, the dingy streets of Chancery, and the foggy, terrifying alleys more intensely through these images. For instance, when he first describes the slum in which Jo lives, Dickens writes:

Now, these tumbling tenements contain, by night, a swarm of misery. As, on the ruined human wretch, vermin parasites appear, so, these ruined shelters have bred a crowd of foul existence that crawls in and out of gaps in walls and boards; and coils itself to sleep, in maggot numbers, where the rain drips in; and comes and goes, fetching and carrying fever, and sowing more evil in its every footprint [...]

The image of teeming maggots on a rain-soaked and "ruined" human body the author describes here is visceral and disgusting. Life in these slums reduces people to their most basic animal needs for survival. Their very existence is made "foul" by their environment. The wet, chilly sensory language of "drips" getting in as the "crowd of foul existence" shifts and warps, "fetching and carrying fever," contributes to the general sense of damp, decay, and revulsion. It is unclear here whether Dickens is referring to actual vermin or to the urban poor themselves when he describes the "swarm of misery" that inhabits these tenements. As he immediately references the disengaged and unpleasant Lords Coodle, Doodle, and Foodle, the author implies that these gentlemen would see little difference between vermin and people.

Even comparatively wealthier parts of Holborn are described as unpleasantly dim and unclean by the narrator, though this might have more to do with their purpose than with the presence of real dirt and filth. Rich and poor areas are also very close to each other, as Dickens regularly mentions. In Chancery Lane, the office of Mr. Vholes in Symond's Inn is described as a:

little, pale, wall-eyed, woe-begone inn, like a large dustbin of two compartments and a sifter. It looks as if Symond were a sparing man in his day, and constructed his inn of old building materials, which took kindly to the dry rot and to dirt and all things decaying and dismal, and perpetuated Symond’s memory with congenial shabbiness.

Rather than being clean and efficient, Vholes's office "takes kindly" to decay and neglect. Slow-acting mold and "dry rot" sets in, making not just the office but the entire "small inn" seem "dismal" and shabby. The atmosphere isn't evil, it's just complacently unappealing, "congenial" in its "shabbiness." It's even quite pitiful and sympathetic in some ways, as Dickens uses gentler language to describe it than the other Inns. It's "little," "pale" and "woe-begone," a neglected child compared to the huge, austere bulk of Lincoln's and Gray's Inns. Compared to the rotten grandeur of Lincoln's Inn, Symond's has a different kind of mildewing unpleasantness. It's not actively malicious, it's just badly kept up and cheaply made, implying that it cannot produce things of quality even if it means well. Finally, then, there's no completely good law court and no completely good neighbourhood of Holborn in Bleak House, no matter how "congenial."

Monthly

Annual (Best Value)

$595USD/mo

Charged $71.40 USD every year

Teacher

Teacher$795USD/mo

Charged $95.40 USD every year

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Instant PDF downloads of all 2251 LitCharts literature guides and of every new one we publish. Try a free sample literature guide.

"Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!"

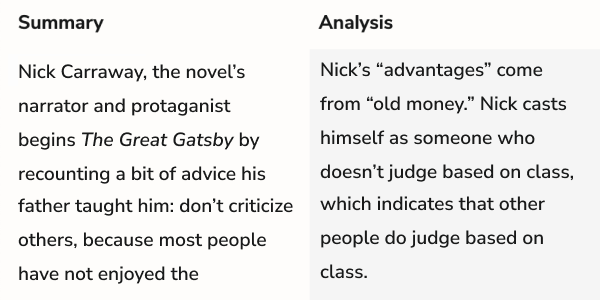

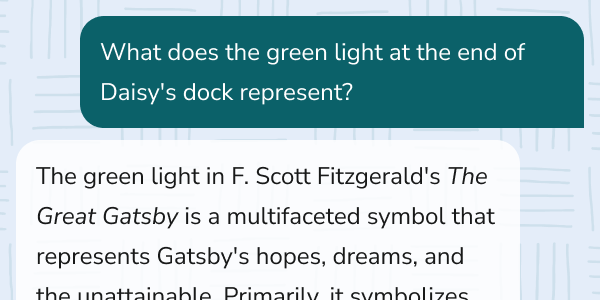

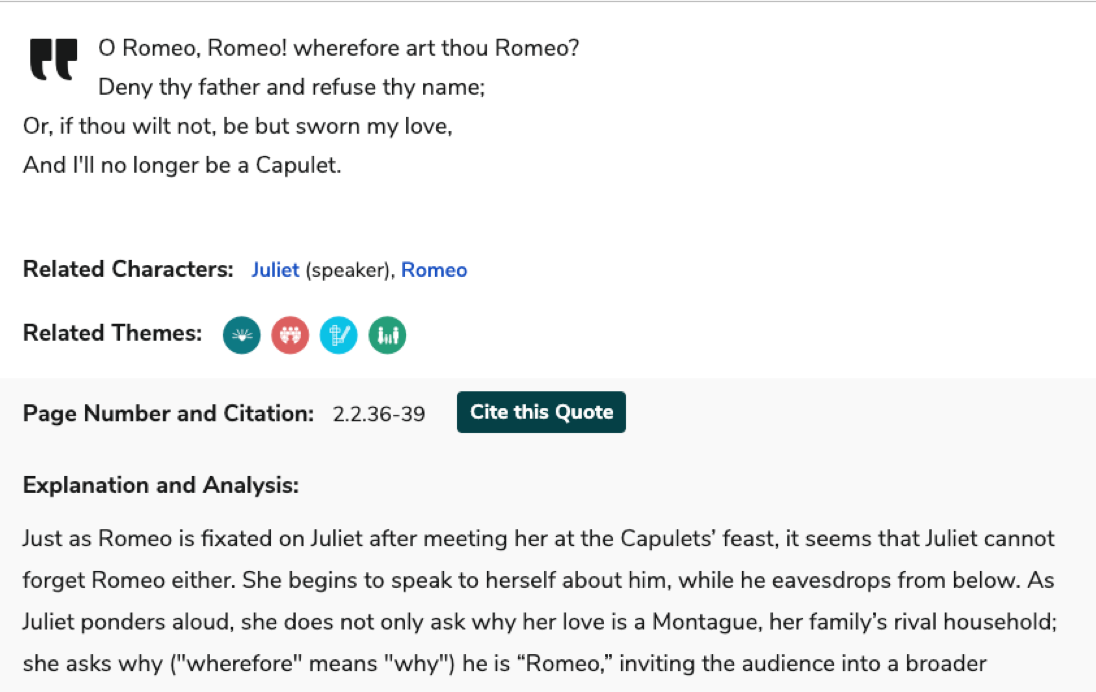

Quotes Explanations

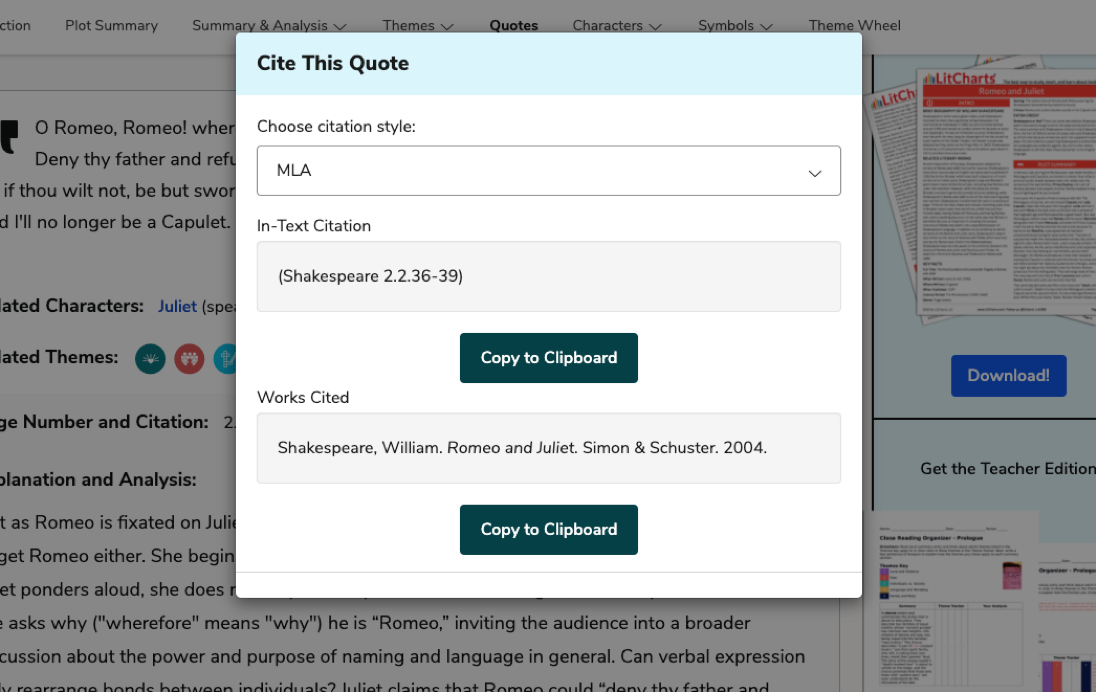

Find the perfect quote. Understand it perfectly. Then rock the citation, too.

For all 50,202 quotes we cover.

For all 50,202 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

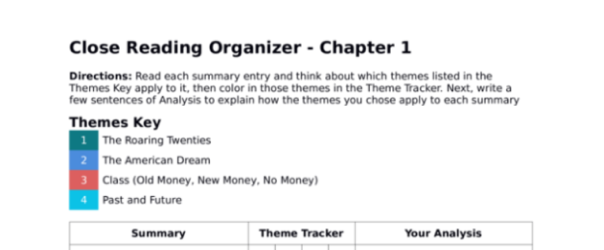

Close reading made easy for students.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

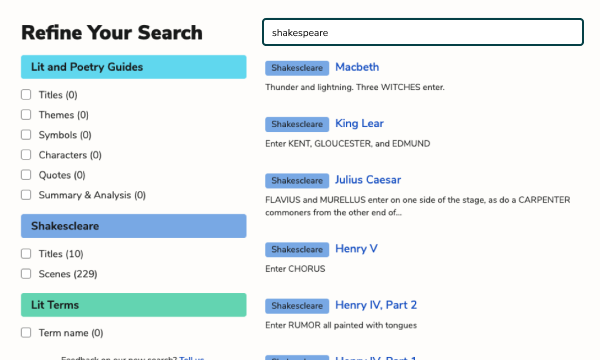

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

Literary Terms and Devices

Definitions and examples for every literary term and device you need to know.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Try a free sample literary term PDF.

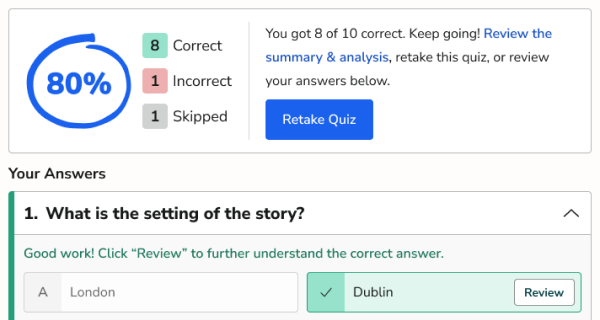

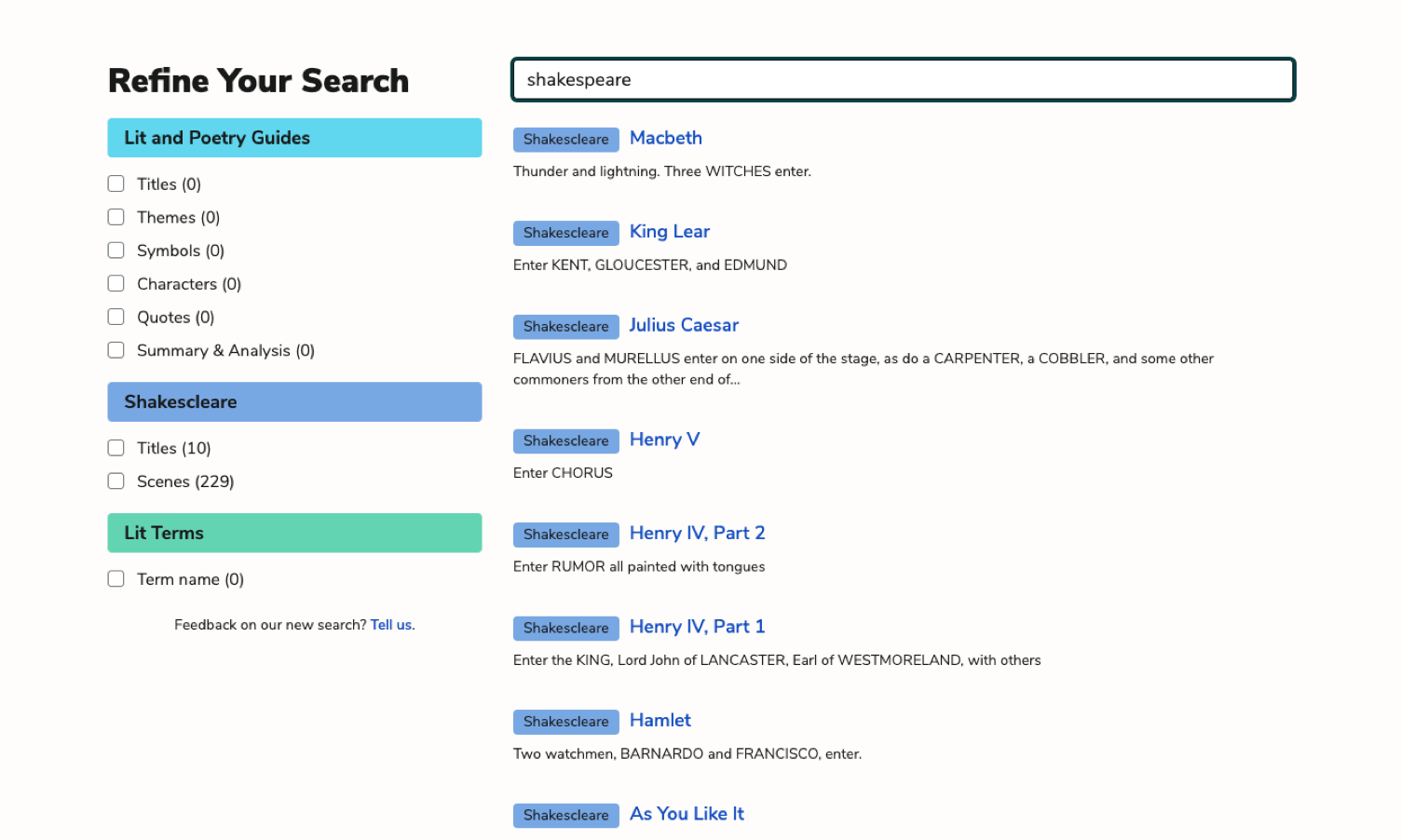

Advanced Search

Refine any search. Find related themes, quotes, symbols, characters, and more.

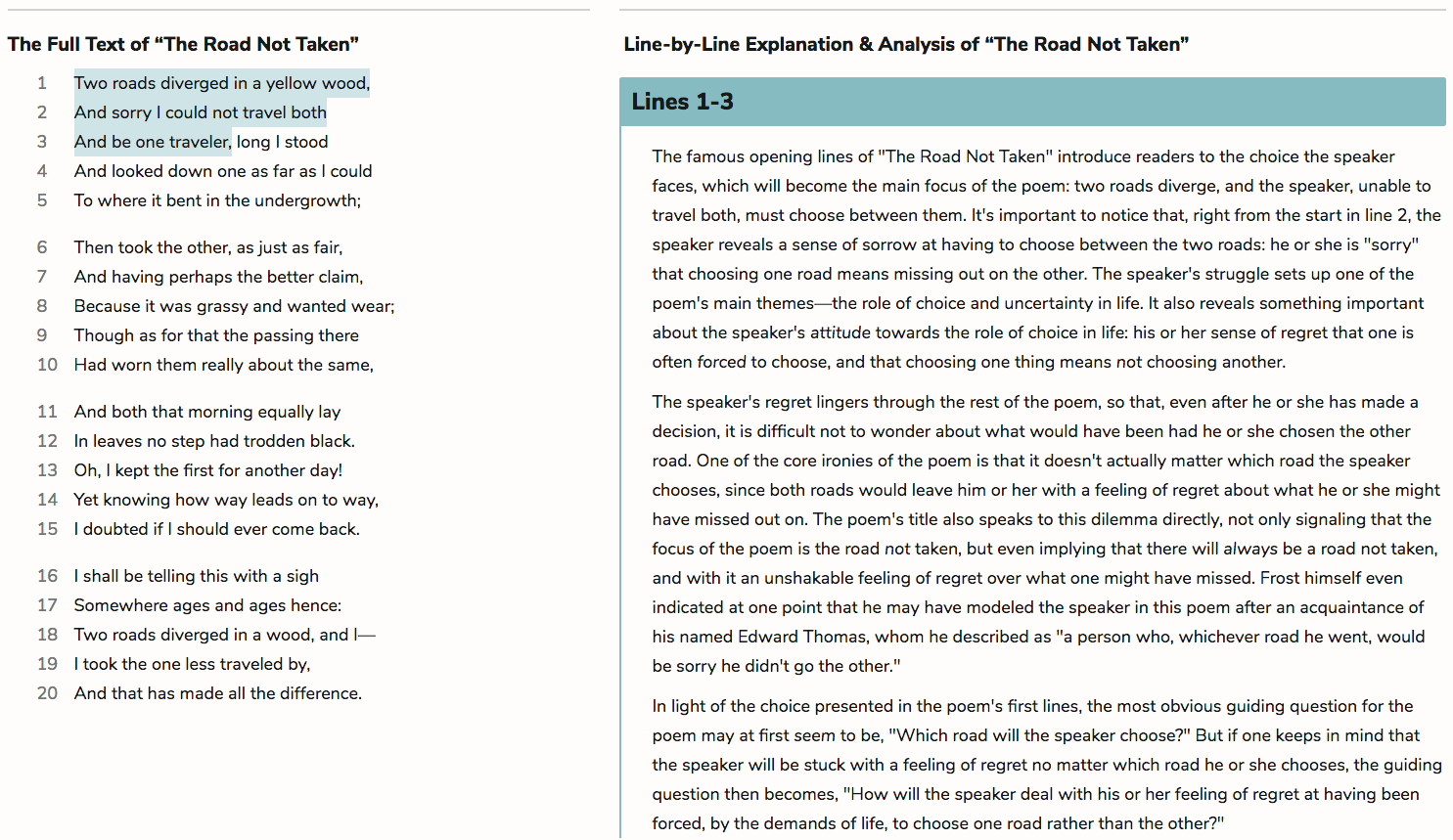

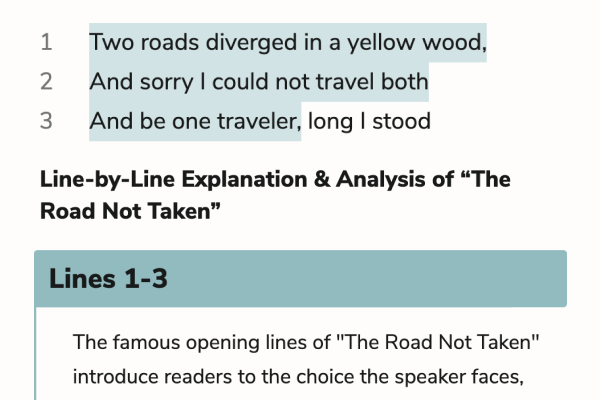

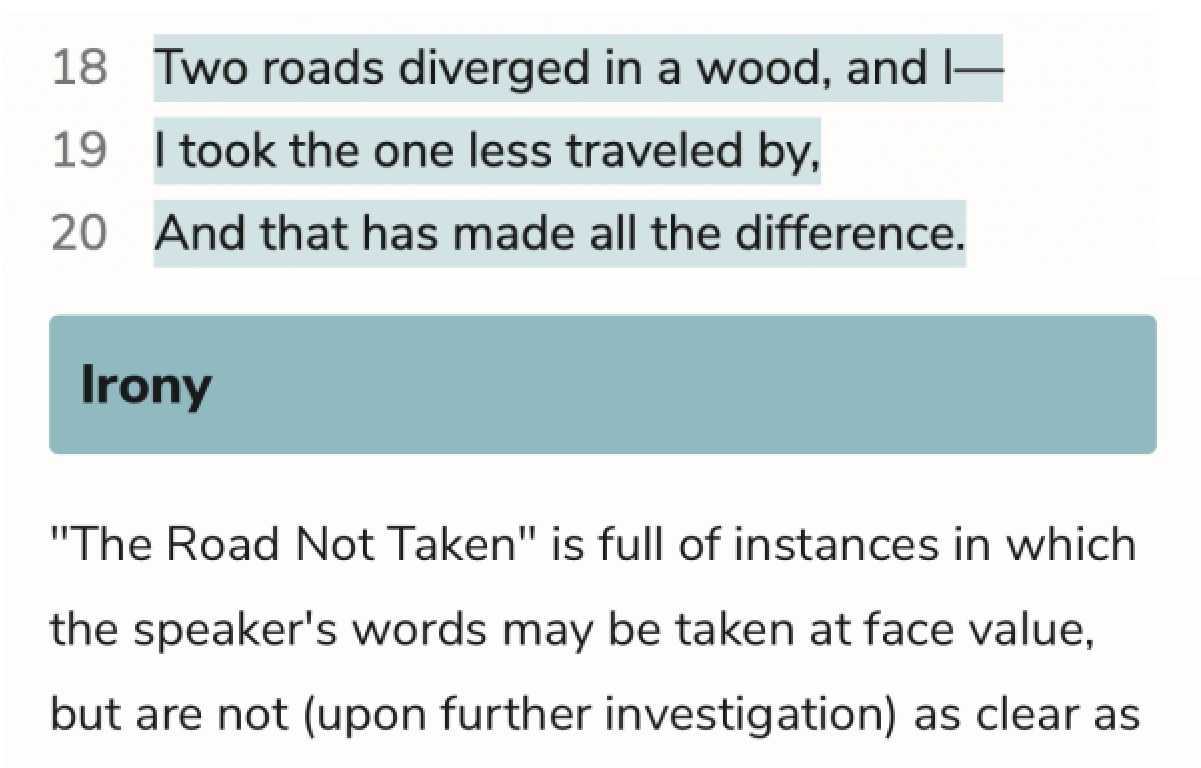

Poetry Guides

Line-by-line explanations and analysis of figurative language and poetic devices.

For every lyric poem we cover.

For every lyric poem we cover.