|

Have questions?

Contact us

Already a member? Sign in

|

Get every literary device explanation for The English PatientPlus so much more...

Sign up for LitCharts A+Get instant access to every literary device explanation, plus so much more...

Metaphor

Explanation and Analysis—The Placenta:

As the English patient lies bed-bound in the Italian villa after being rescued from his aviation crash, Hana grapples with the reality of becoming his full-time caretaker. Burdened with war trauma herself, she finds it difficult to sleep and often spends time in deep reminiscence over her first encounters with the fragile and scarred patient. In Chapter 2, Ondaatje compares the English patient to an unborn baby, crafting a metaphor to illustrate how war injuries have almost infantilized the patient:

In the Pisa hospital she had seen the English patient for the first time. A man with no face. An ebony pool. All identification consumed in a fire. [...] Sometimes she collects several blankets and lies under them, enjoying the warmth they bring. And when moonlight slides onto the ceiling it wakes her, and she lies in the hammock, her mind skating. [...] Her legs move under the burden of military blankets. She swims in their wool as the English patient moved in his cloth placenta.

By using the image of a placenta as a metaphor for the English patient's fragility, Ondaatje heightens the image of the patient’s fetus-like nature. Because the patient is so badly burned, he relies on Hana—almost like a mother—to feed, wash, and take care of him. His blankets represent a placenta because they keep him in place, they keep him warm, and he is unable to move from their confines—like an unborn baby in the womb. This figurative image is particularly striking because the English patient is a grown adult; yet his injuries have reduced his physical capabilities almost to the point of elimination. His mind remains sharp, and he can recall memories of his past and communicate with Hana, but he remains entirely immobile. This metaphor also gestures to the gendered dynamic between Hana and the patient, for Hana—the novel's primary female character—has no choice but to tend to the male patient before she tends to herself.

Monthly

Annual (Best Value)

$595USD/mo

Charged $71.40 USD every year

Teacher

Teacher$795USD/mo

Charged $95.40 USD every year

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Instant PDF downloads of all 2247 LitCharts literature guides and of every new one we publish. Try a free sample literature guide.

"Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!"

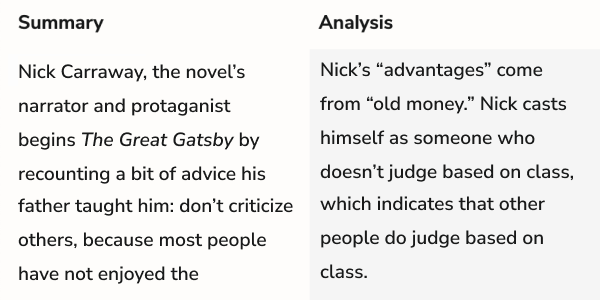

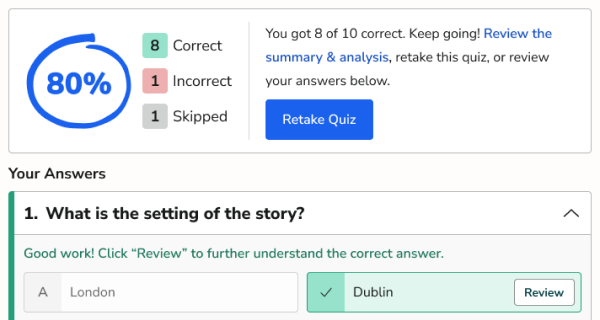

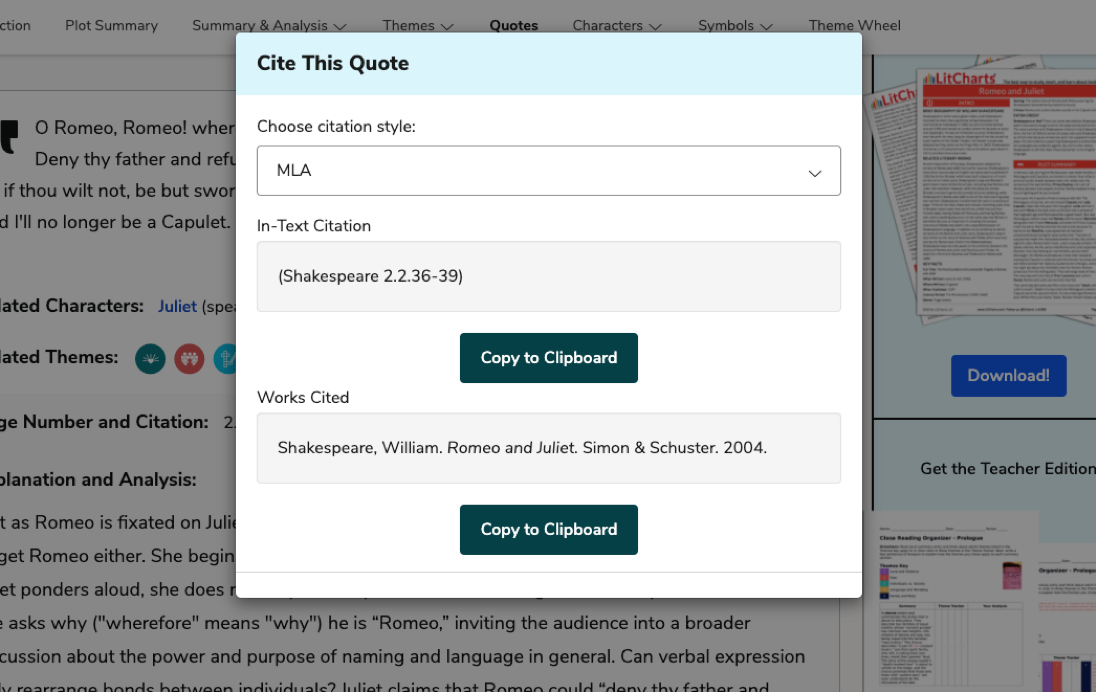

Quotes Explanations

Find the perfect quote. Understand it perfectly. Then rock the citation, too.

For all 50,101 quotes we cover.

For all 50,101 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

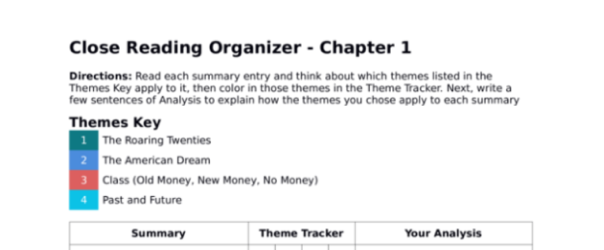

Close reading made easy for students.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

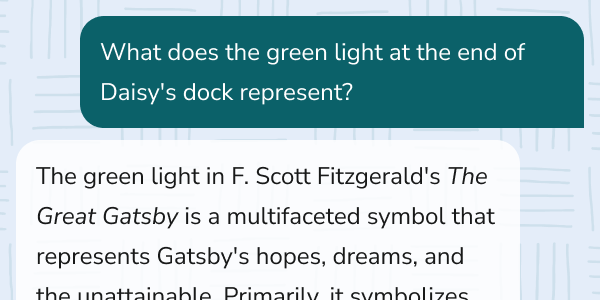

Literary Terms and Devices

Definitions and examples for every literary term and device you need to know.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Try a free sample literary term PDF.

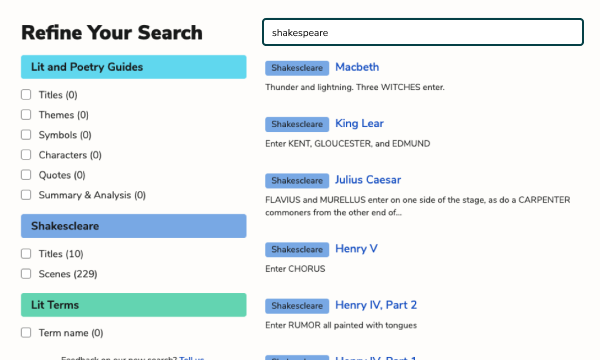

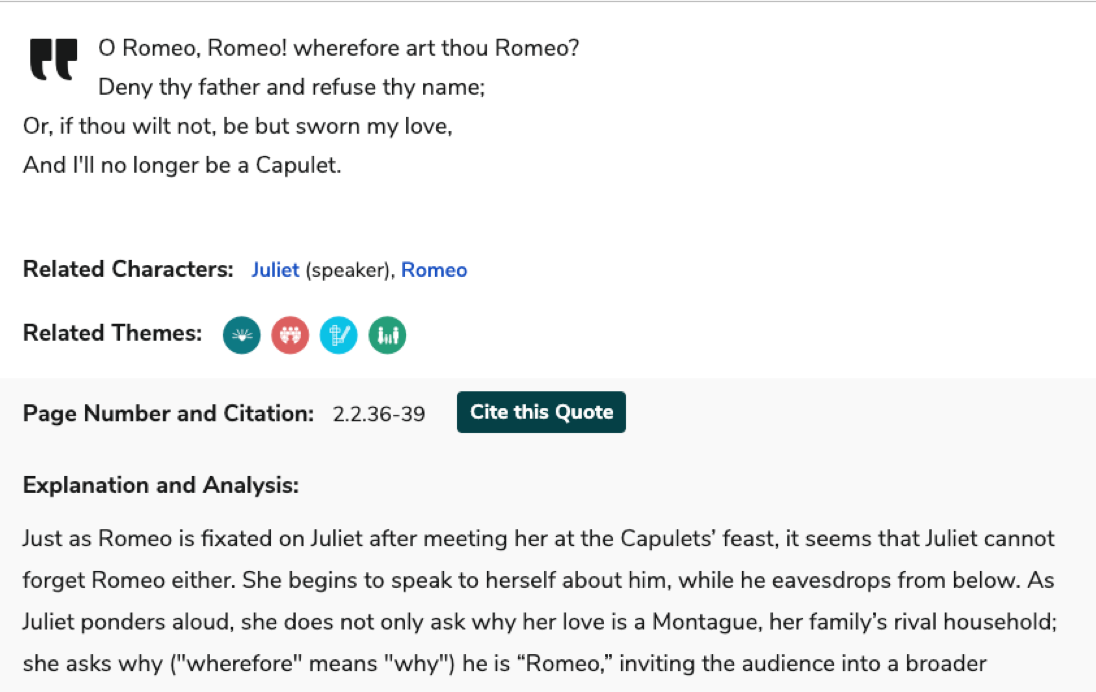

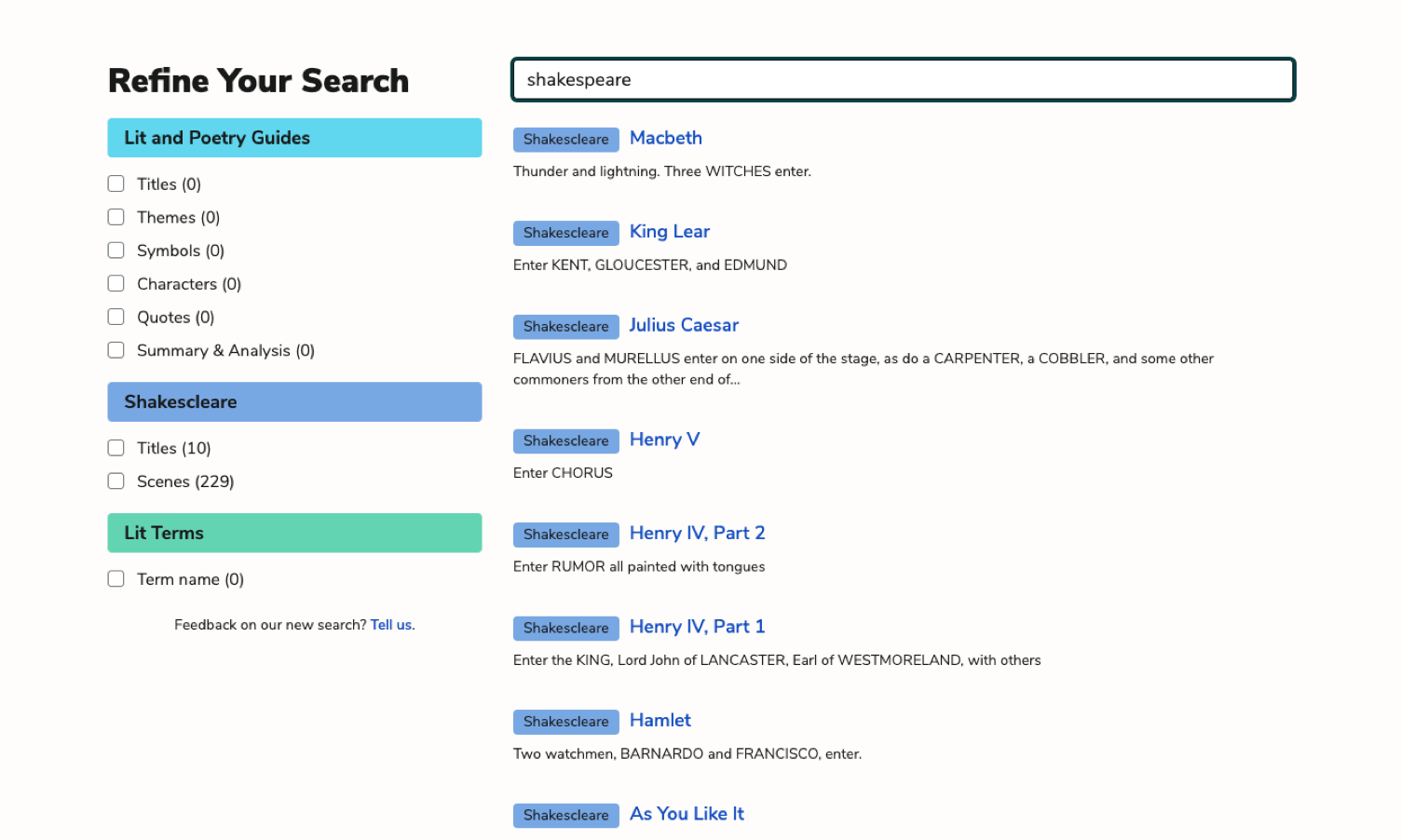

Advanced Search

Refine any search. Find related themes, quotes, symbols, characters, and more.

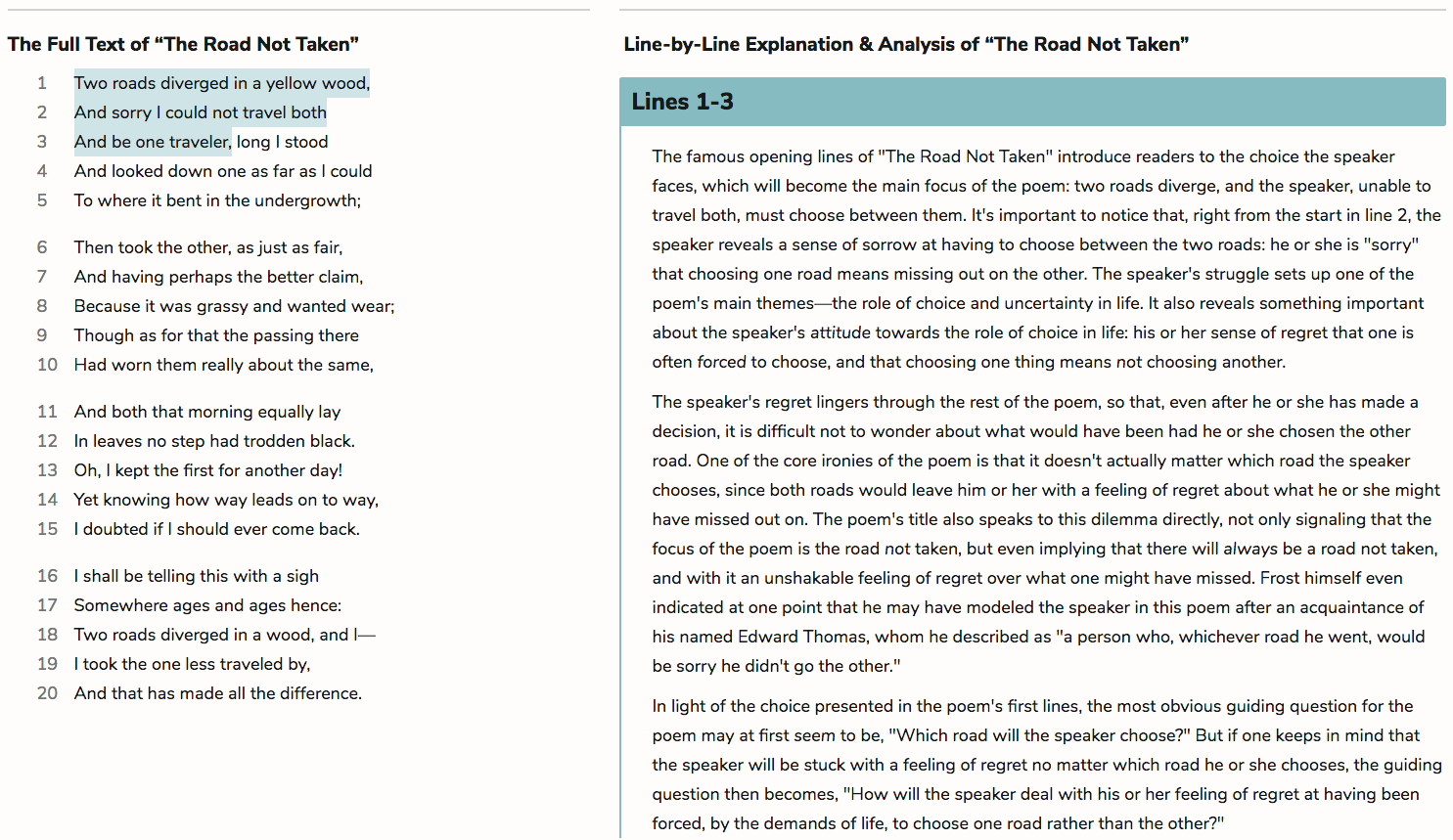

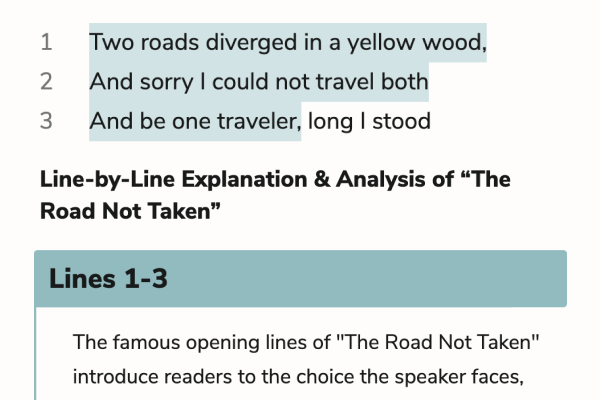

Poetry Guides

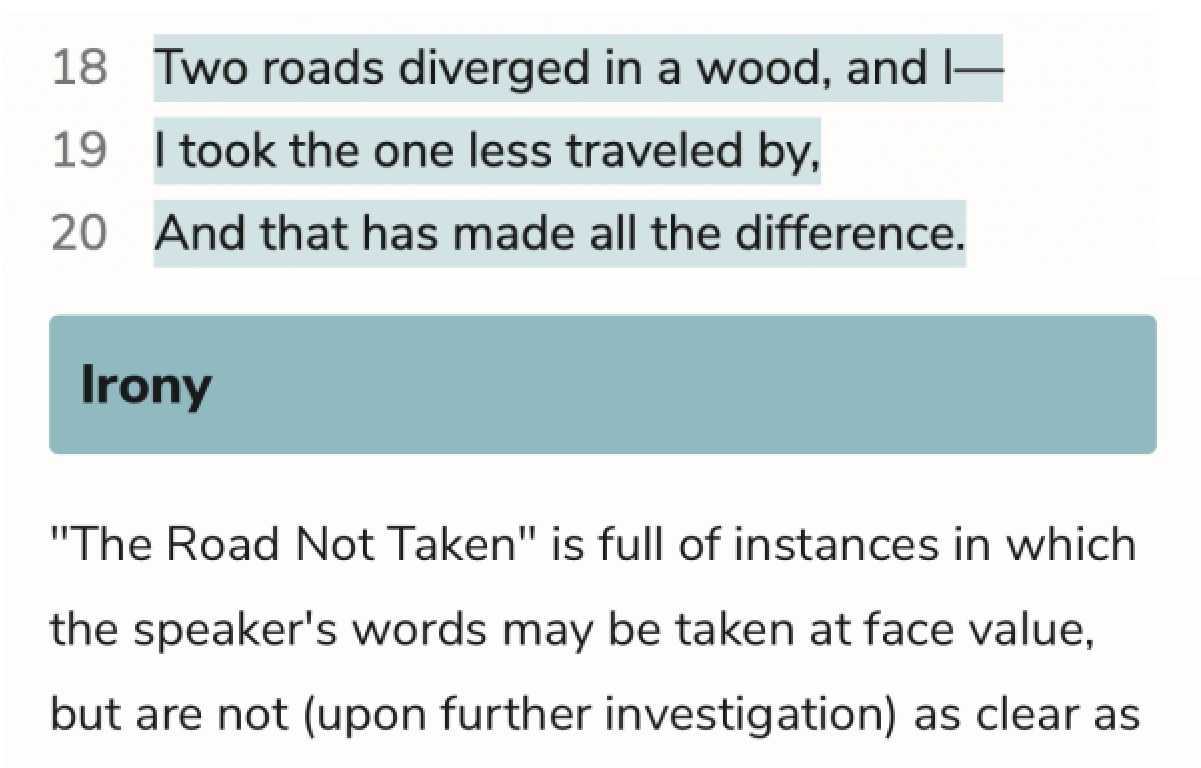

Line-by-line explanations and analysis of figurative language and poetic devices.

For every lyric poem we cover.

For every lyric poem we cover.