|

Have questions?

Contact us

Already a member? Sign in

|

Get every literary device explanation for American PastoralPlus so much more...

Sign up for LitCharts A+Get instant access to every literary device explanation, plus so much more...

Metaphor

Explanation and Analysis—A War for Him:

In Chapter 3, Jerry Levov metaphorically compares the Swede's existence to a war. This metaphor emphasizes the adversity that the Swede experienced beneath his simple, conventional surface—something which went completely unnoticed by Nathan Zuckerman.

In a conversation with Zuckerman at their high school reunion, Jerry acknowledges that his brother was "a very nice, simple, stoical guy" and that he in one way "could be conceived as completely banal and conventional." After talking at length about the seeming banality of his brother's "ordinary decent life," he employs a metaphor to articulate that the Swede's existence was everything but benign.

But what he was trying to do was to survive, keeping his group intact. He was trying to get through with his platoon intact. It was a war for him, finally. [...] He got caught in a war he didn't start, and he fought to keep it all together, and he went down.

While Jerry speaks these words, neither Zuckerman nor the reader knows about Merry and the Old Rimrock bombing. This missing context makes the war metaphor seem exaggerated. While Zuckerman and the reader still just see the Swede as the ordinary guy that Jerry initially described, this dramatic description of the Swede's desperation to "survive" and keep "his group intact" makes it clear that there's more behind the Swede's surface.

And sure enough, just after this, Jerry brings up "little Merry's darling bomb." This information adds a layer to the war metaphor. While the war Jerry initially describes his brother waging as purely figurative, Merry's bomb is no metaphor.

As Jerry elaborates on the difficulties that plagued the Swede's family life, these layers intertwine. For instance, when he says that the Swede's life "was blown up by that bomb" or that the bomb "detonated his life," he sustains the war metaphor all while discussing a literal bomb. Roth plays with the same effect at the very end of Part 1, when Zuckerman writes that "after turning their living room into a battlefield, after turning Morristown High into a battlefield, [Merry] went out one day and blew up the post office." Here, a figure of speech once again gives way to something literal—with real-life consequences.

By intertwining figurative violence and on-the-ground violence, Roth illustrates the high-stakes atmosphere of the late 1960s, for with Merry's convictions, violent resistance to the Vietnam War was necessary for making Americans understand what they were implicated in on the other side of the world. On one of the last pages of the novel, Roth again uses the word "war" in multiple ways to convey the many layers of conflict and struggle depicted in the novel: "It was not the specific war that she'd had in mind, but it was a war, nonetheless, that she brought home to America—home into her very own house."

Monthly

Annual (Best Value)

$595USD/mo

Charged $71.40 USD every year

Teacher

Teacher$795USD/mo

Charged $95.40 USD every year

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Instant PDF downloads of all 2248 LitCharts literature guides and of every new one we publish. Try a free sample literature guide.

"Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!"

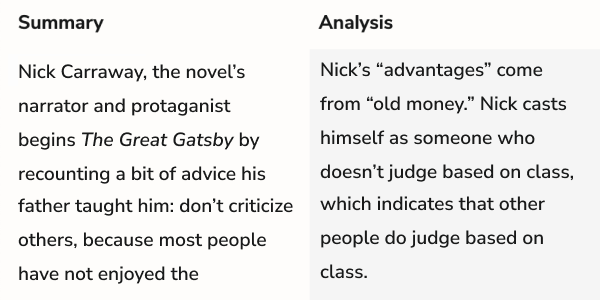

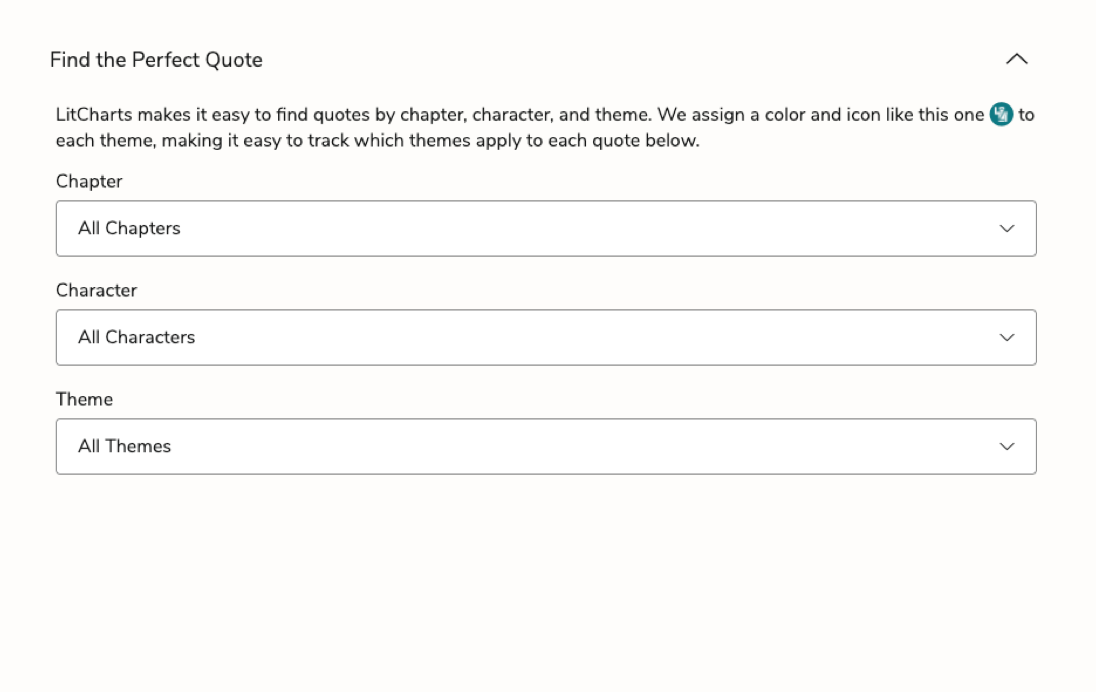

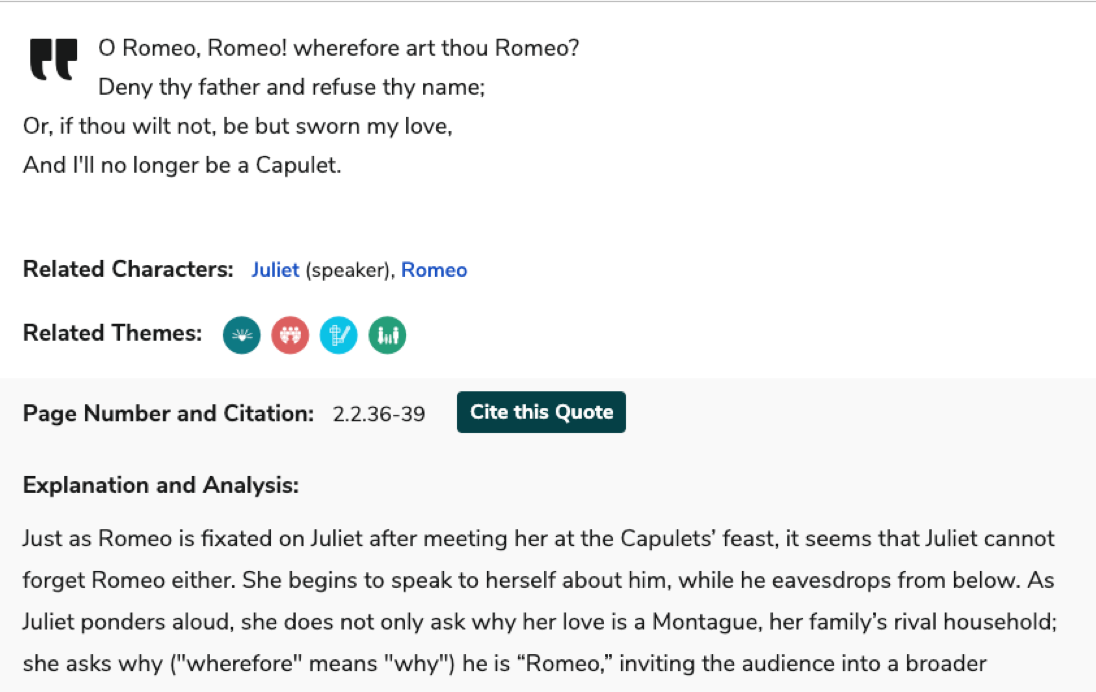

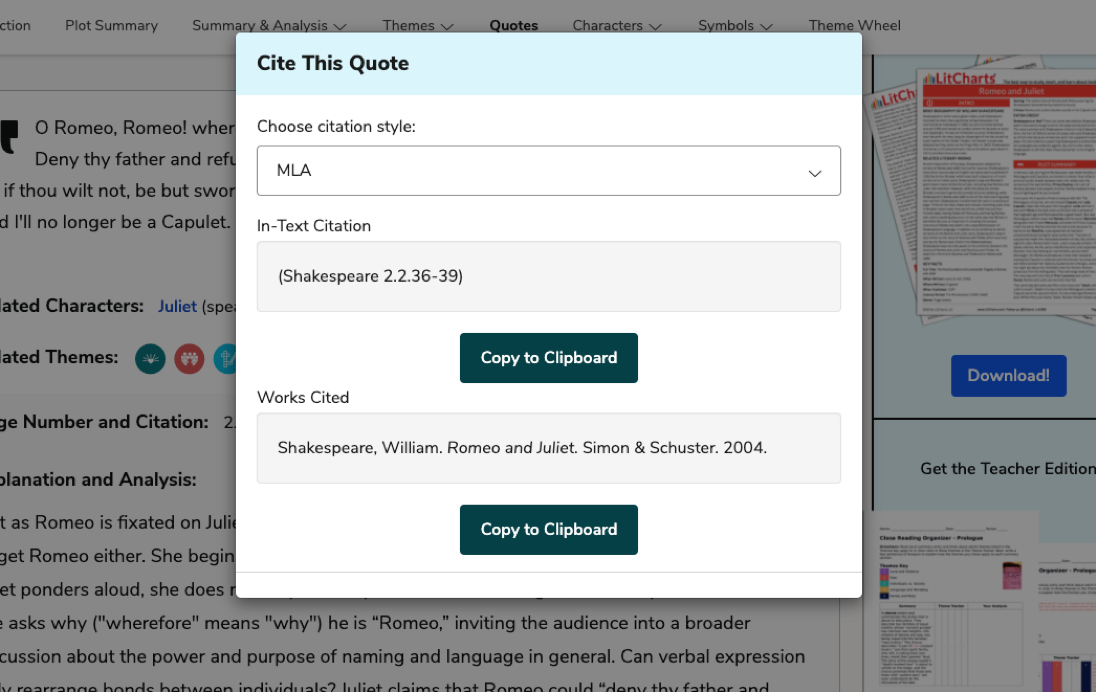

Quotes Explanations

Find the perfect quote. Understand it perfectly. Then rock the citation, too.

For all 50,127 quotes we cover.

For all 50,127 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

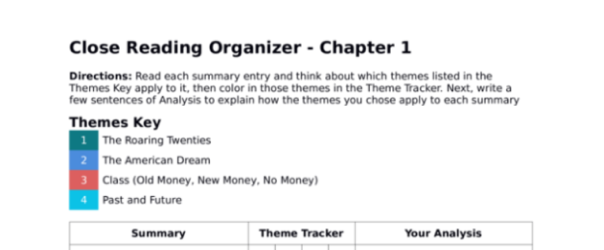

Close reading made easy for students.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

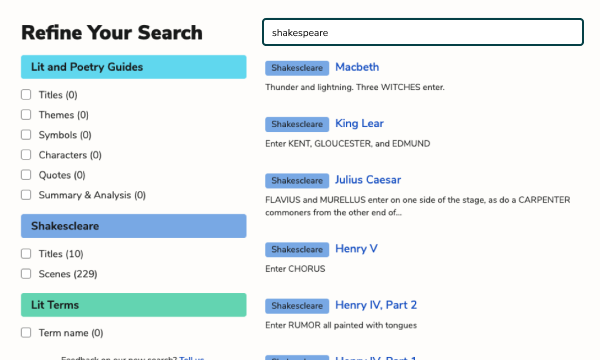

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

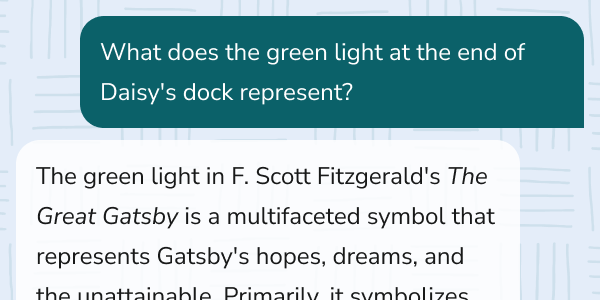

Literary Terms and Devices

Definitions and examples for every literary term and device you need to know.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Try a free sample literary term PDF.

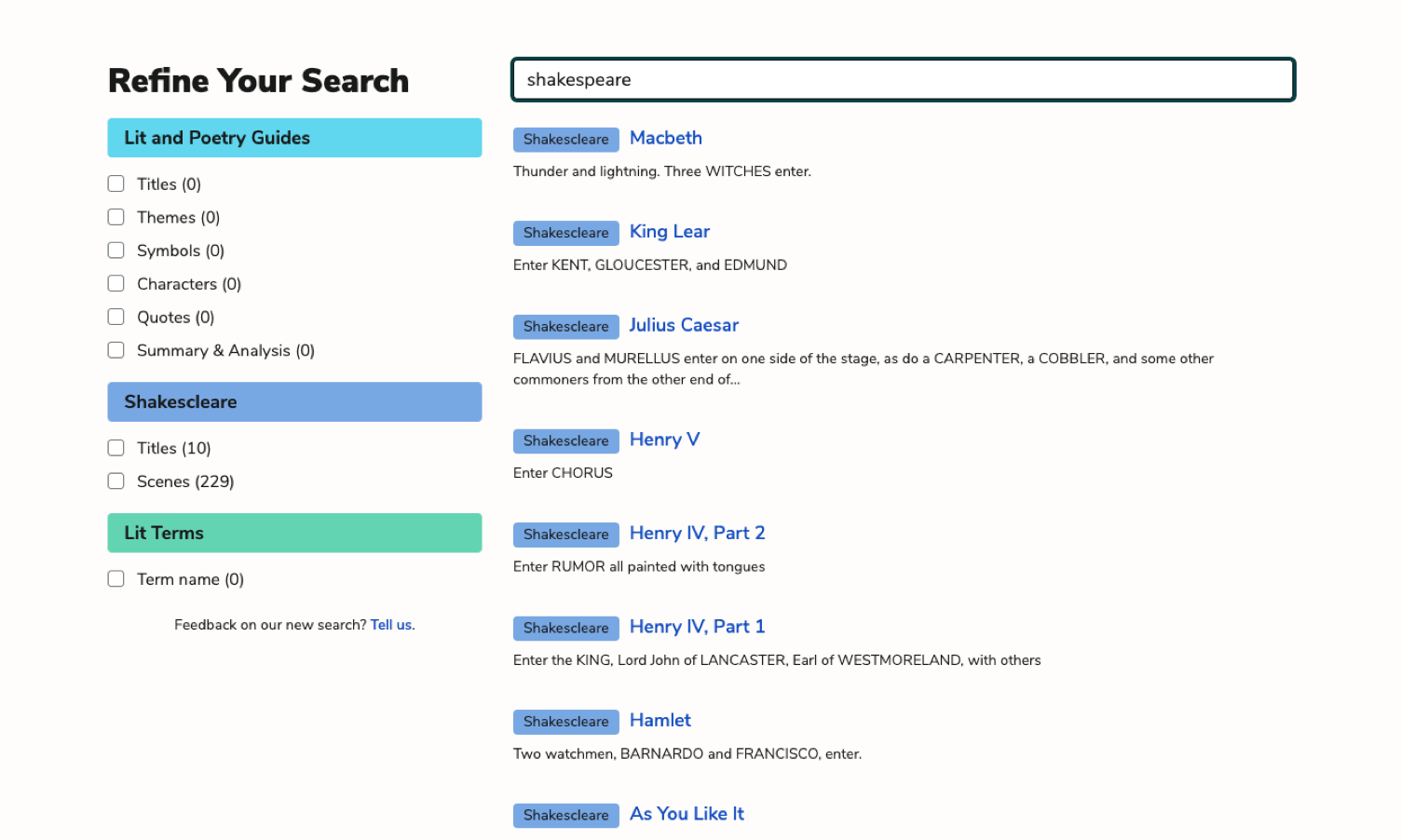

Advanced Search

Refine any search. Find related themes, quotes, symbols, characters, and more.

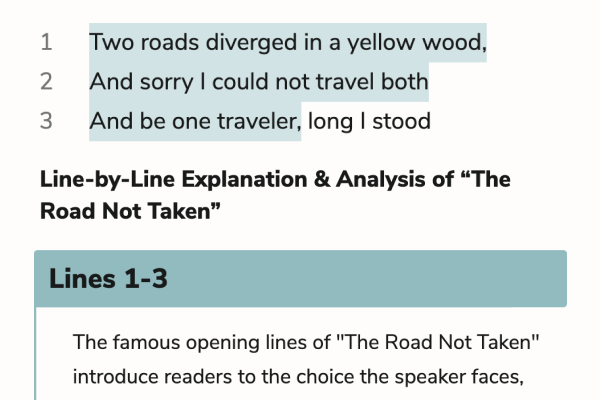

Poetry Guides

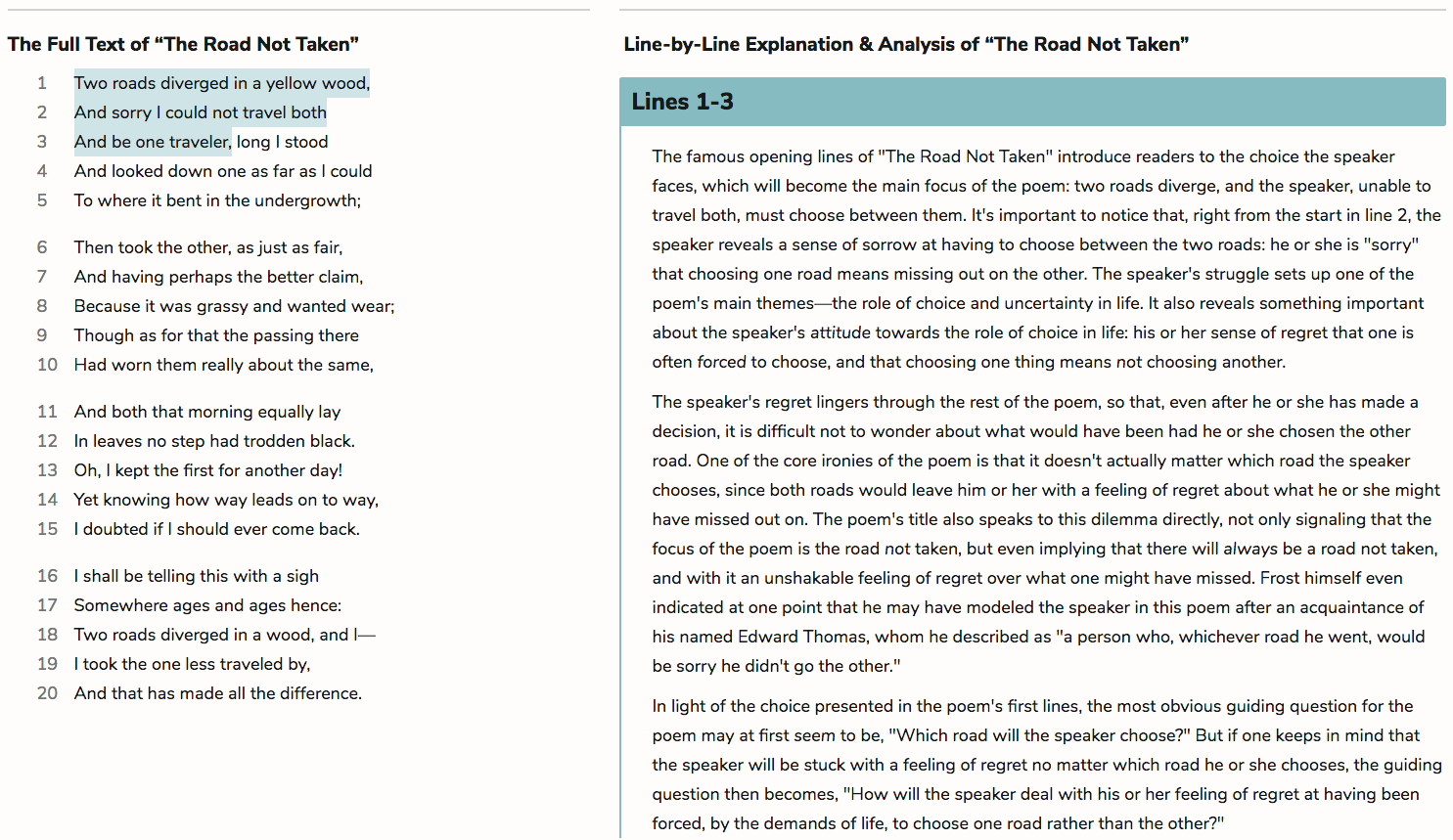

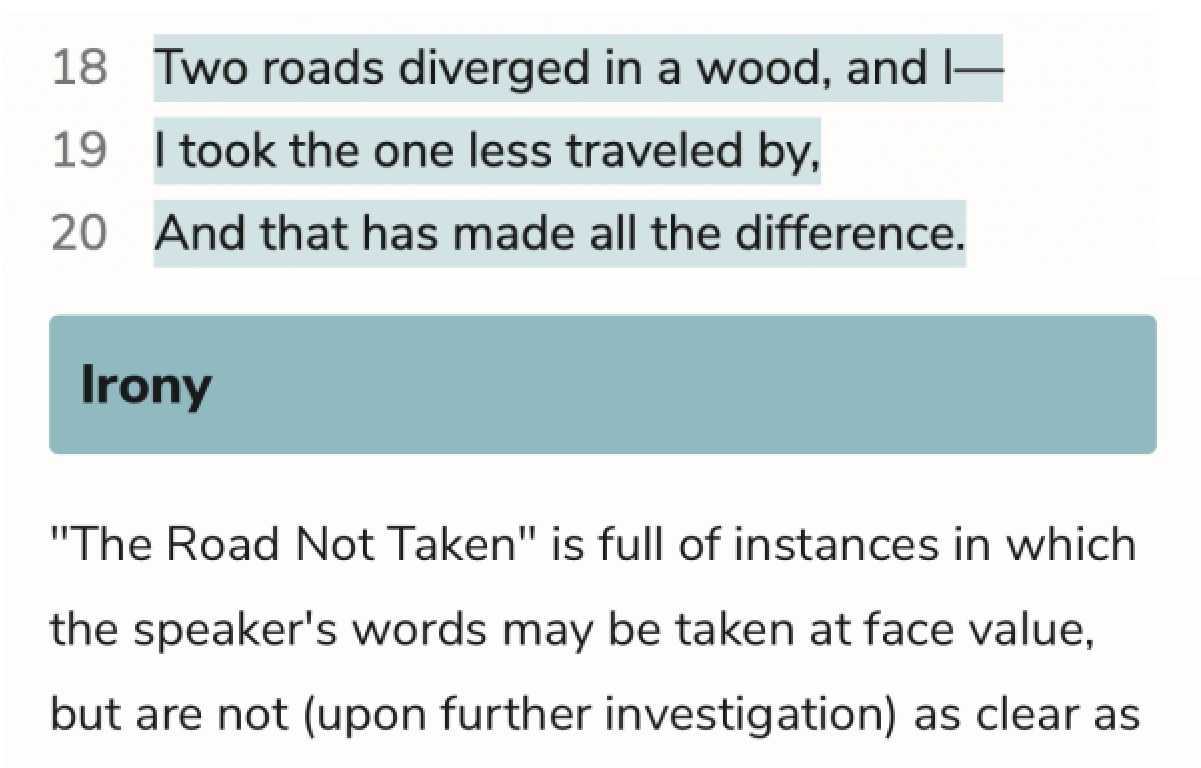

Line-by-line explanations and analysis of figurative language and poetic devices.

For every lyric poem we cover.

For every lyric poem we cover.