|

Have questions?

Contact us

Already a member? Sign in

|

Get every literary device explanation for Oliver TwistPlus so much more...

Sign up for LitCharts A+Get instant access to every literary device explanation, plus so much more...

Metaphor

Explanation and Analysis—Oliver's Resurrection:

Oliver's evolving relationship to graves, coffins, and deathbeds throughout the novel is an extended metaphor for his upward trajectory. He is born on his mother's deathbed and nearly dies himself in Chapter 1:

The fact is, that there was considerable difficulty in inducing Oliver to take upon himself the office of respiration,—a troublesome practice, but one which custom has rendered necessary to our easy existence,—and for some time he lay gasping on a little flock mattress, rather unequally poised between this world and the next, the balance being decidedly in favour of the latter.

For Victorians, birth and death often happened in the same bed, so the "little flock mattress" represents a threshold between heaven and earth. Oliver defies everyone's expectations by failing to follow his mother out of "this world." Throughout his early childhood, the only thing anyone seems to expect of him is that he will waste away and die like his friend Dick. In Chapter 4, Mrs. Sowerberry underscores this expectation by asking him whether he will mind sleeping under the counter with the undertaker's inventory of coffins:

"[...] it doesn't much matter whether you will or not, for you won't sleep any where else. [...]"

The Sowerberrys have only taken a halfhearted chance on Oliver's future, failing to make space for him in a real bed. The parish and the Sowerberrys toss him in with coffins as though they expect that they will have to put him in one eventually anyway. High childhood mortality rates in Victorian England partially explain this behavior, even if it is cruel. Oliver's frequent encounters with coffins and deathbeds from a young age symbolize his especially abysmal odds of making it far in life.

When Oliver is taken in by the Maylies, he gets a real bed, where:

He felt calm and happy, and could have died without a murmur.

Oliver's health is gradually restored, and he finds that his new bed is not for dying, but for sleeping. This change reorients Oliver's relationship to graves, coffins, and deathbeds. In Chapter 32, Oliver visits a graveyard near the Maylies' house:

Oliver often wandered here, and, thinking of the wretched grave in which his mother lay, would sometimes sit him down and sob unseen; but, as he raised his eyes to the deep sky overhead, he would cease to think of her as lying in the ground, and weep for her sadly, but without pain.

Oliver learns in this passage to imagine the graveyard as a place to grieve and as a place where neither he nor his mother belong permanently. He understands that his mother has departed the graveyard for heaven, and that he will eventually leave the graveyard to go home. Later, when Rose Maylie falls ill and the narrator describes her as "tottering on the deep grave's edge," it becomes even clearer that Oliver, by contrast, has risen from his mother's deathbed. He has his whole life ahead of him.

Monthly

Annual (Best Value)

$595USD/mo

Charged $71.40 USD every year

Teacher

Teacher$795USD/mo

Charged $95.40 USD every year

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Instant PDF downloads of all 2250 LitCharts literature guides and of every new one we publish. Try a free sample literature guide.

"Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!"

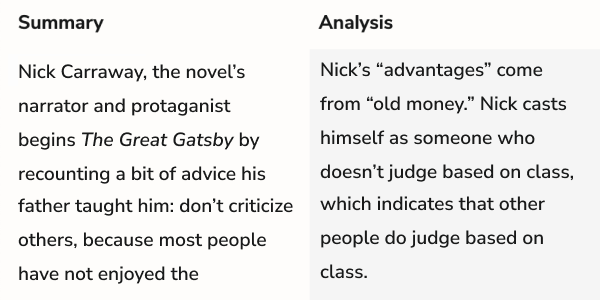

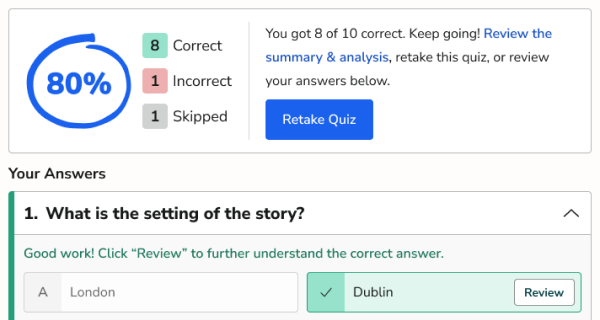

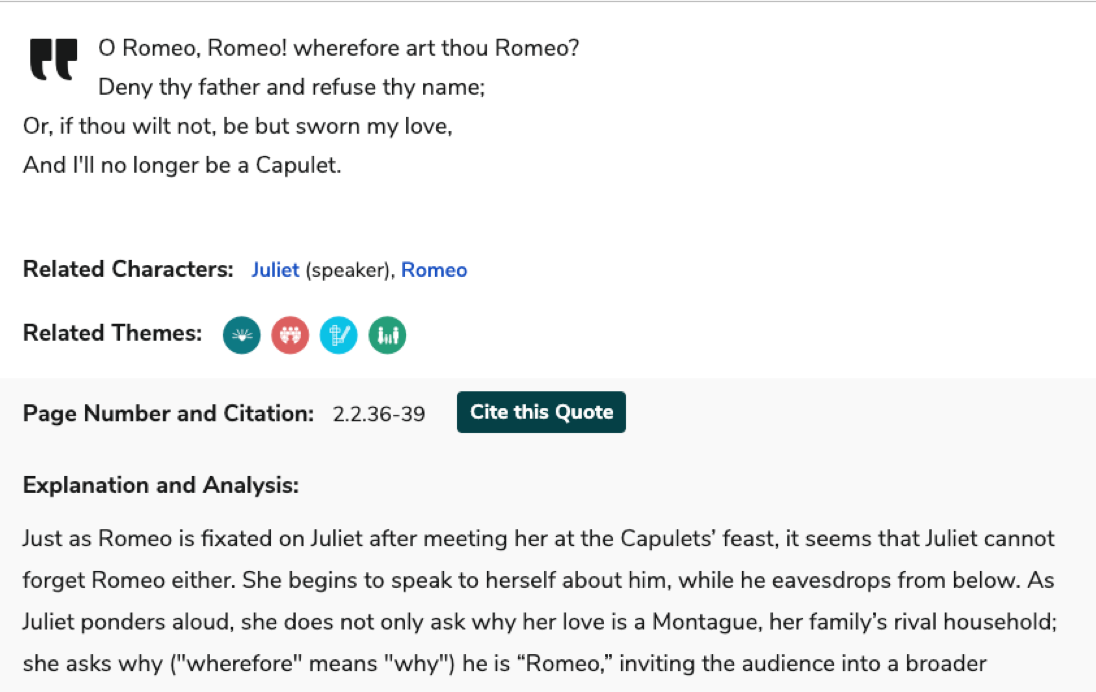

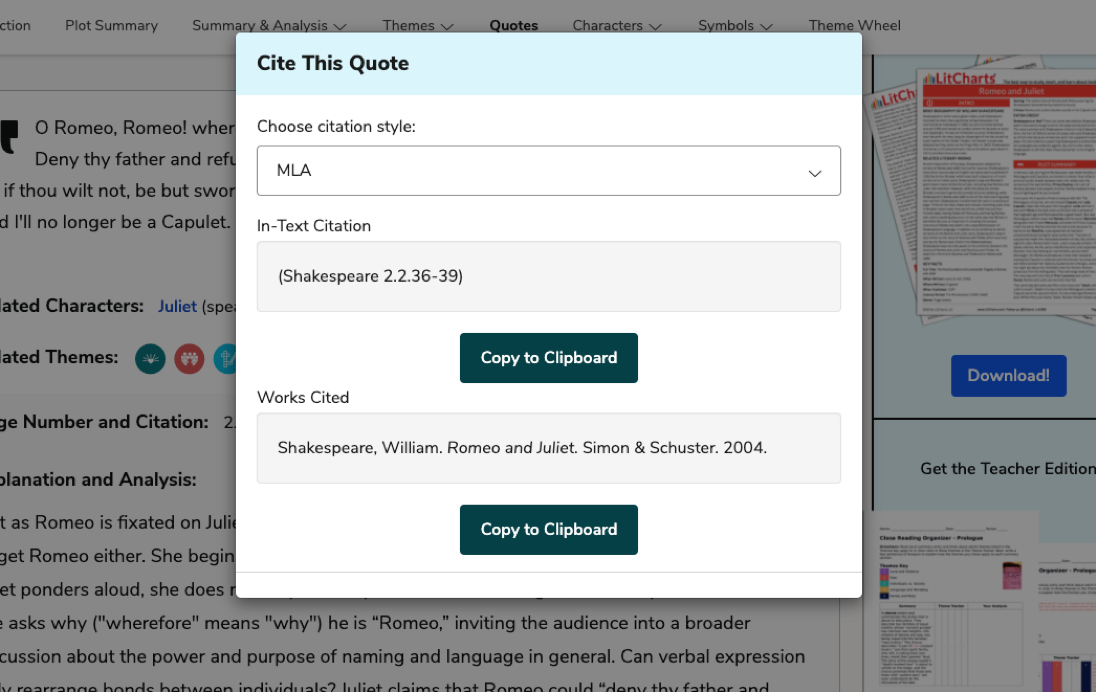

Quotes Explanations

Find the perfect quote. Understand it perfectly. Then rock the citation, too.

For all 50,177 quotes we cover.

For all 50,177 quotes we cover.

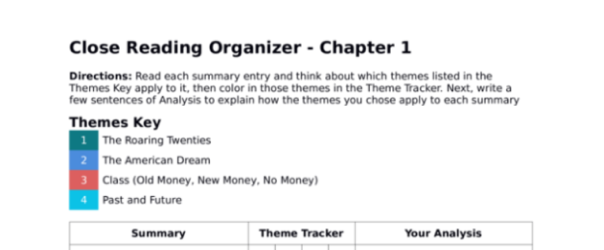

Teacher Editions

Close reading made easy for students.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

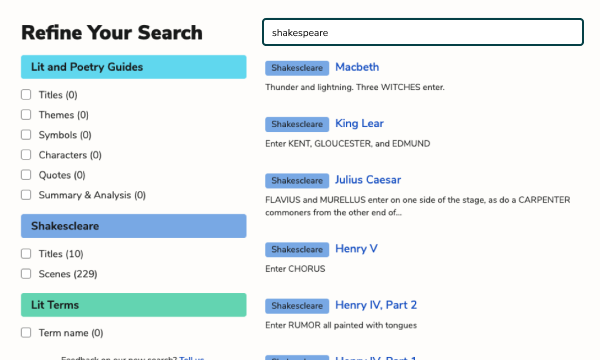

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

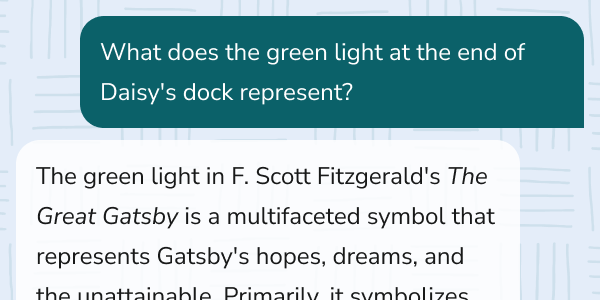

Literary Terms and Devices

Definitions and examples for every literary term and device you need to know.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Try a free sample literary term PDF.

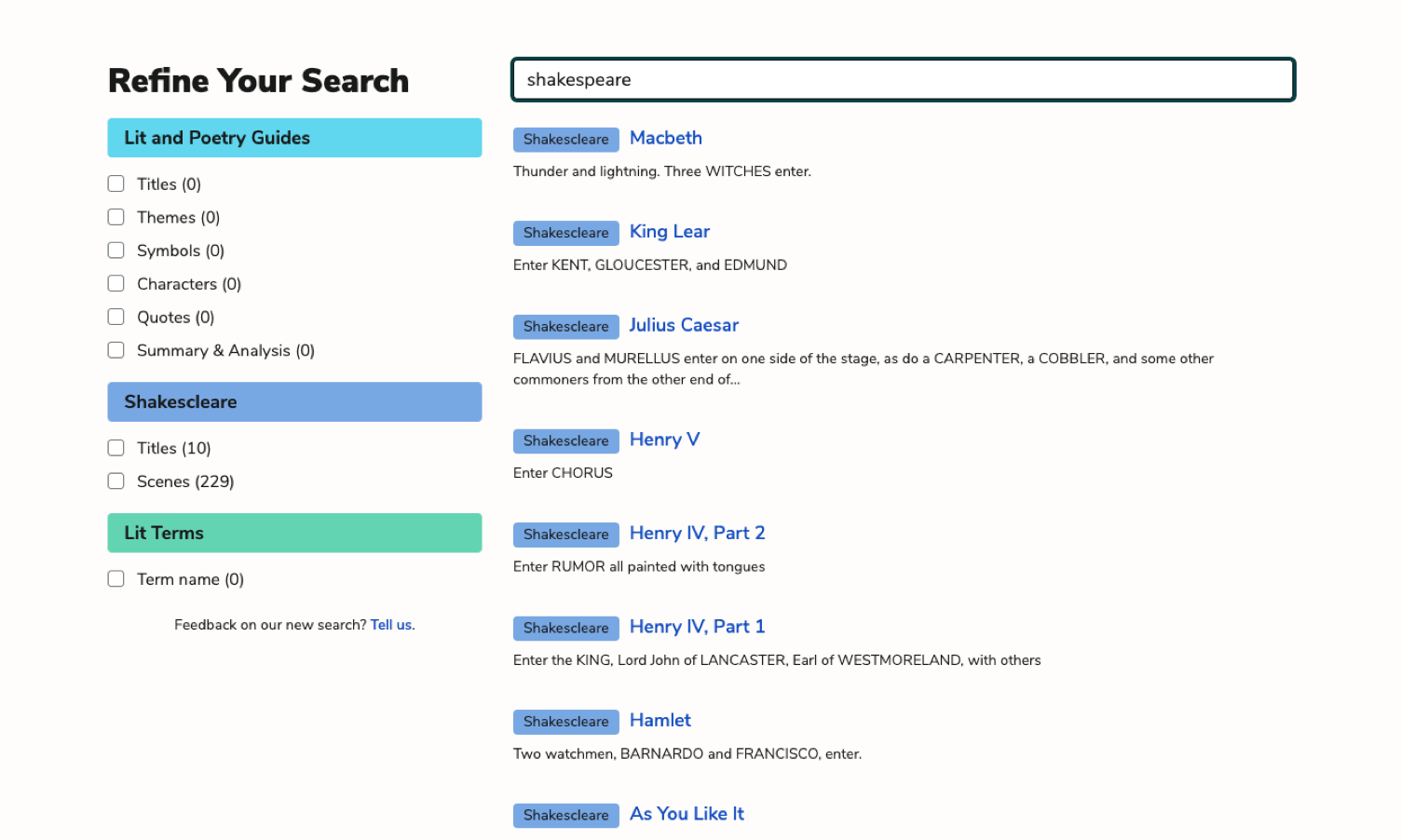

Advanced Search

Refine any search. Find related themes, quotes, symbols, characters, and more.

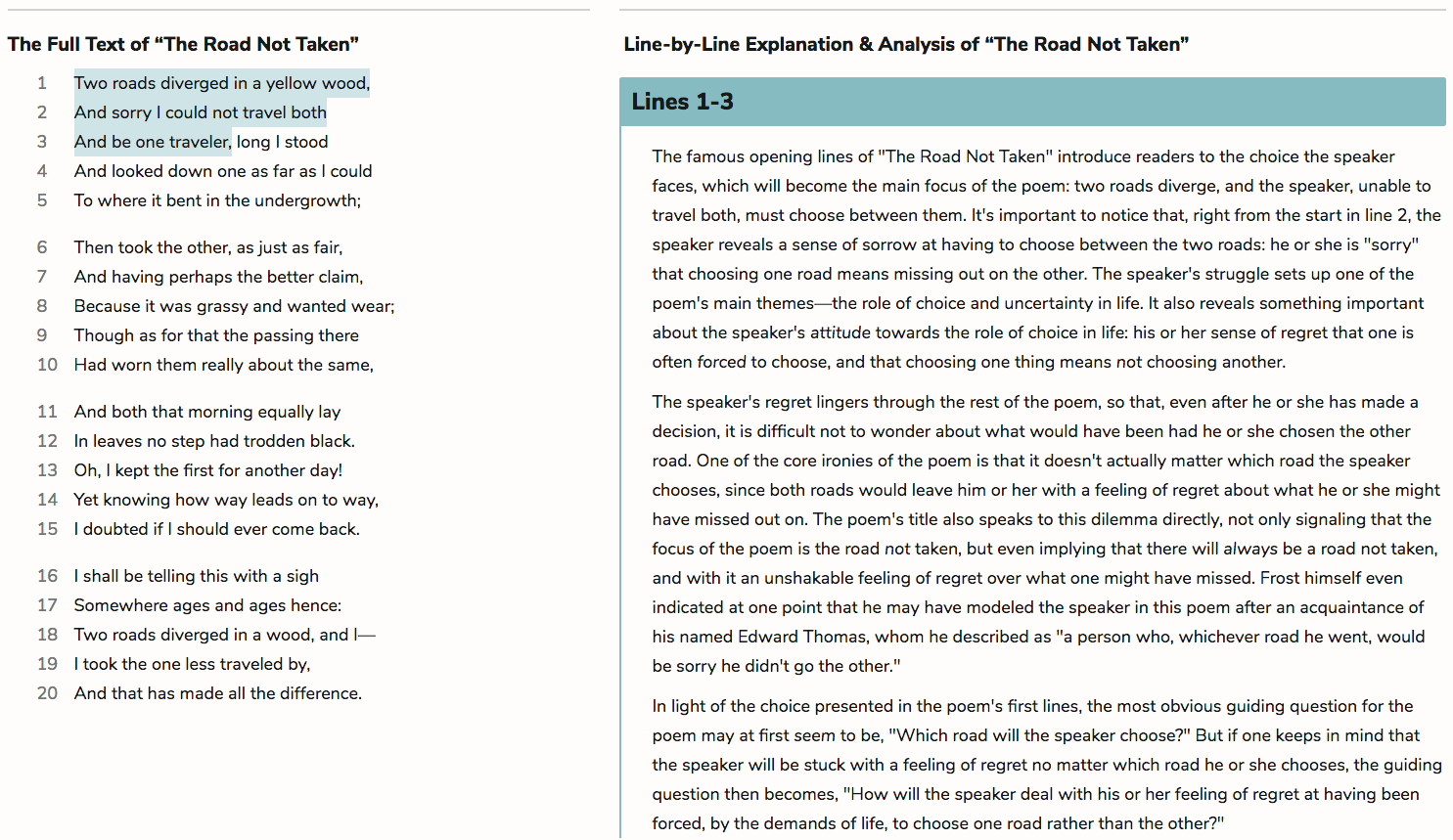

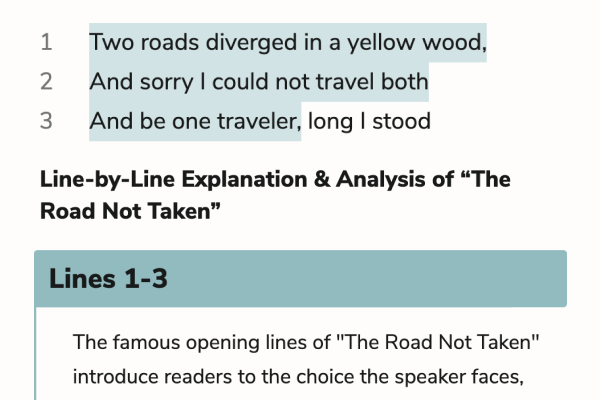

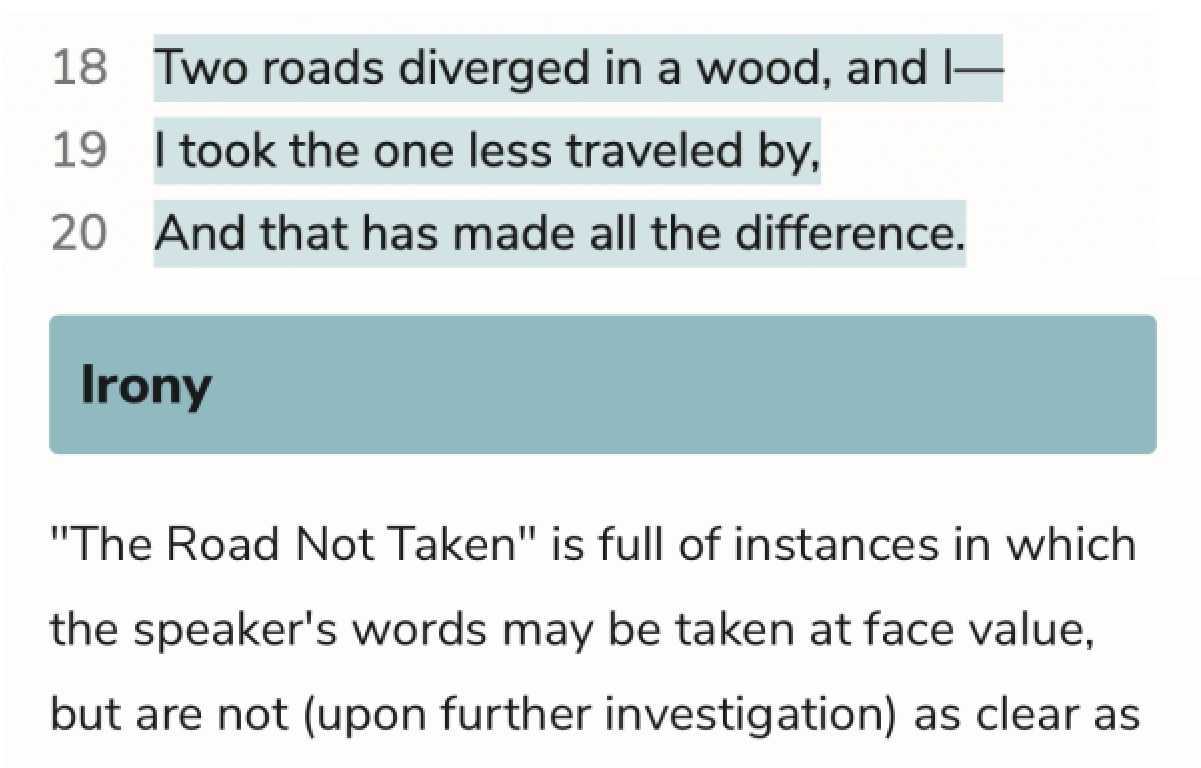

Poetry Guides

Line-by-line explanations and analysis of figurative language and poetic devices.

For every lyric poem we cover.

For every lyric poem we cover.