|

Have questions?

Contact us

Already a member? Sign in

|

Get every literary device explanation for Just MercyPlus so much more...

Sign up for LitCharts A+Get instant access to every literary device explanation, plus so much more...

Motif

Explanation and Analysis—Relentless Hope:

One important motif in the book is relentless hope in the face of despair. Stevenson uses this motif as a form of pathos to convince his readers not to give up on criminal justice reform, as bleak as the picture may look. One moving instance of the motif occurs in Chapter 4, when Herbert Richardson pleads with Stevenson to take his case:

Mr. Stevenson, I’m sorry, but you have to represent me. I don’t need you to tell me that you can stop this execution; I don’t need you to say you can get a stay. But I have twenty-nine days left, and I don’t think I can make it if there is no hope at all. Just say you’ll do something and let me have some hope.

By the time Herbert calls the EJI, his execution is scheduled in 30 days. Legal processes move slowly, so this leaves little room for Stevenson to usher the case through the red tape of the appeals process, let alone build a convincing argument for the sentencing to be overturned. What's more, Stevenson has just lost two cases that ended in horrific executions for his clients. At first, he turns Herbert down: he has neither the time nor the emotional resources to take on such a difficult case.

Stevenson instantly feels ashamed of the "bureaucratic demurrals" he offered to Herbert over the phone, and he is relieved that Herbert calls him back. At first, Stevenson seems focused on redeeming himself through a more human followup conversation. However, it becomes "impossible for [Stevenson] to say no" once Herbert explains what his help would mean. "I have twenty-nine days left," Herbert says, "and I don't think I can make it if there is no hope at all. Just say you'll do something and let me have some hope." Stevenson realizes that arguing Herbert's case is about more than winning. It is also about giving Herbert the feeling that someone is trying to help him. Little as the hope may be, it is what Herbert needs to get through the harrowing wait before he is set to be electrocuted. The way Herbert clings to hope gives Stevenson the courage and resolve to fight another losing battle.

By Chapter 11, Stevenson has started to see that just as a good legal defense allows his clients to hope, hope is necessary to his work as well. When Minnie expresses optimism about Walter's case, Stevenson stops himself from trying to temper it:

I wasn’t exactly sure how to manage the family’s expectations. I felt I was supposed to be the cautionary voice that prepared family members for the worst even while I urged them to hope for the best. It was a task that was growing in complexity as I handled more cases and saw the myriad ways that things could go wrong. But I was developing a maturing recognition of the importance of hopefulness in creating justice.

Stevenson has often thought of himself as the pragmatic and sometimes cynical expert in his clients' cases. He wants them to hope, but he always fears that they will be disappointed. The more cases he argues, the more he sees "the myriad ways that things could go wrong." Still, even he is beginning to find that hope is the thing that keeps him going. Without hope, everyone might stop striving to "create justice" and would instead give in to despair that there is no better world ahead.

Monthly

Annual (Best Value)

$595USD/mo

Charged $71.40 USD every year

Teacher

Teacher$795USD/mo

Charged $95.40 USD every year

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

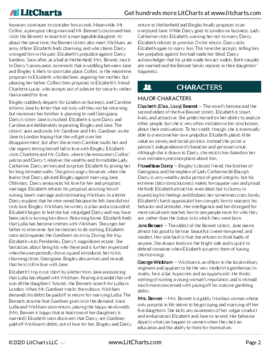

Instant PDF downloads of all 2247 LitCharts literature guides and of every new one we publish. Try a free sample literature guide.

"Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!"

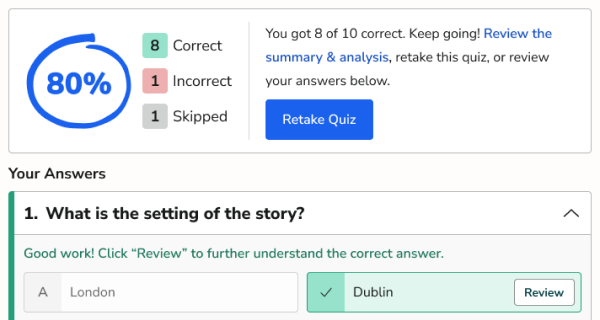

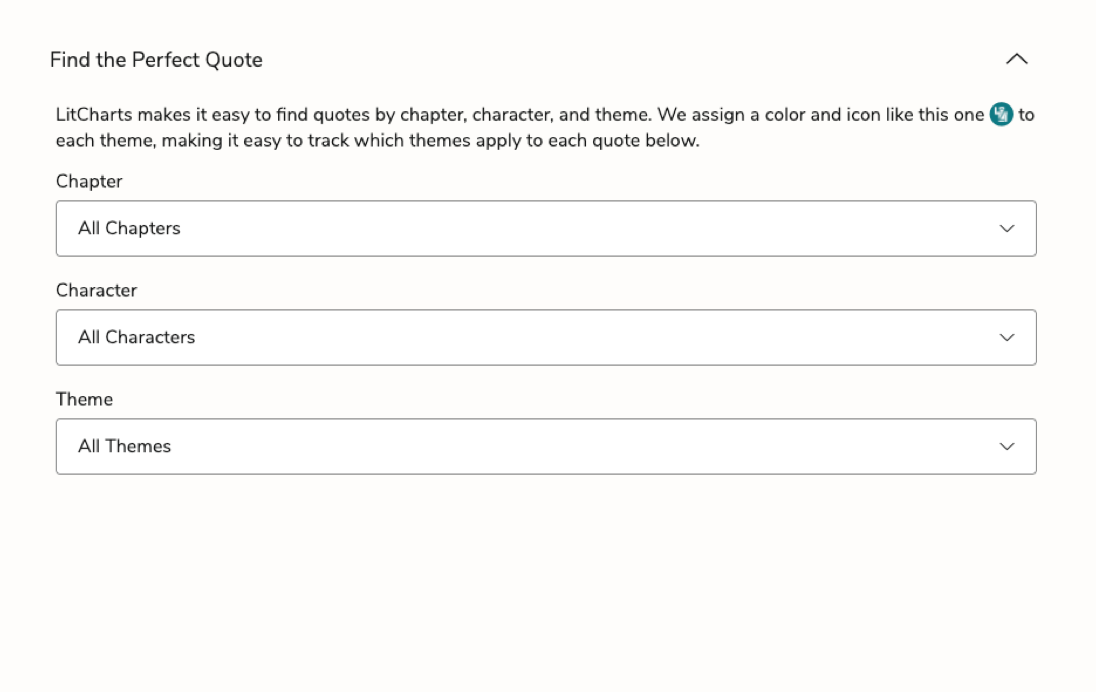

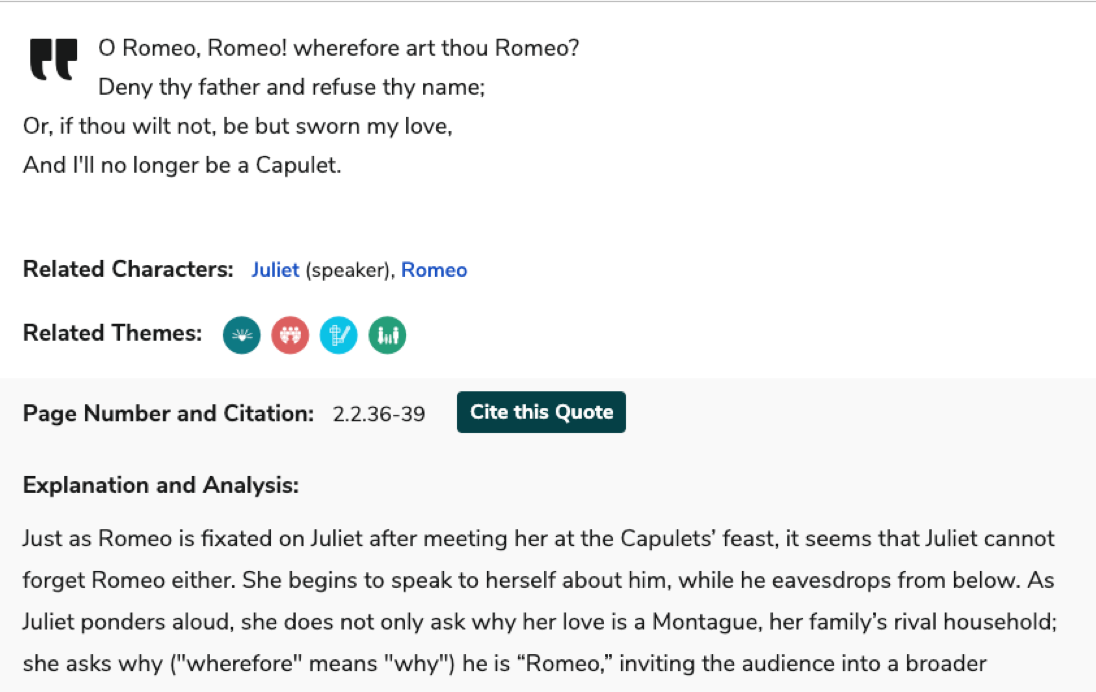

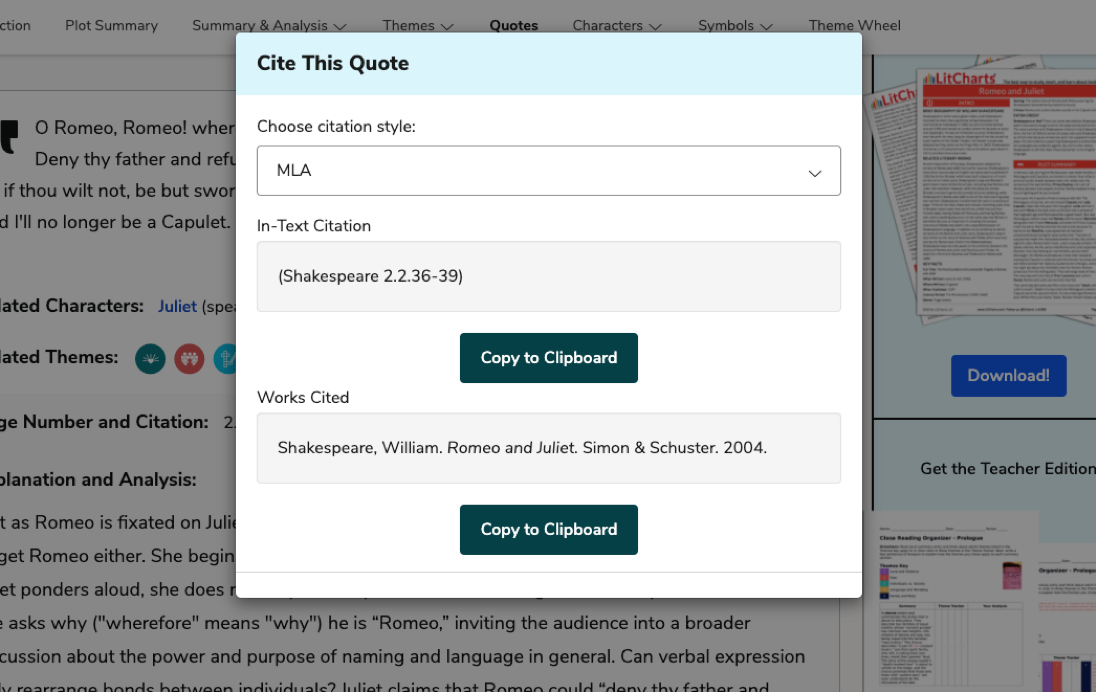

Quotes Explanations

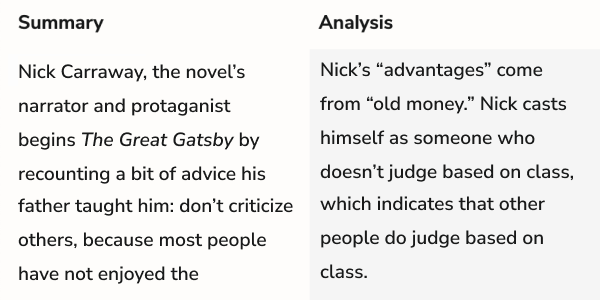

Find the perfect quote. Understand it perfectly. Then rock the citation, too.

For all 50,101 quotes we cover.

For all 50,101 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

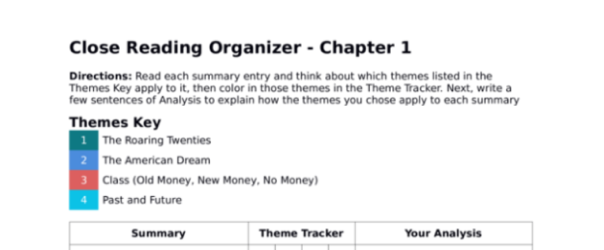

Close reading made easy for students.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

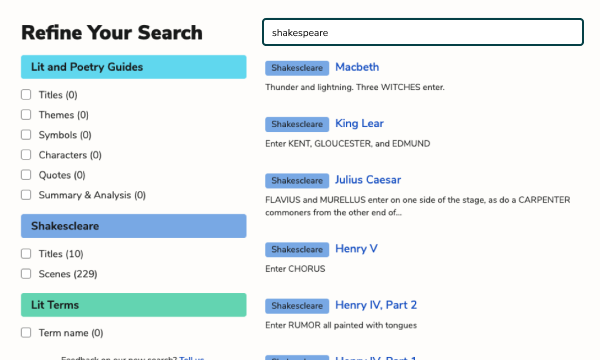

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

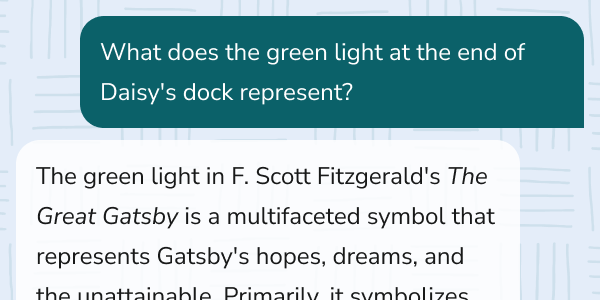

Literary Terms and Devices

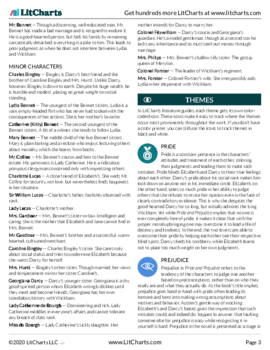

Definitions and examples for every literary term and device you need to know.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Try a free sample literary term PDF.

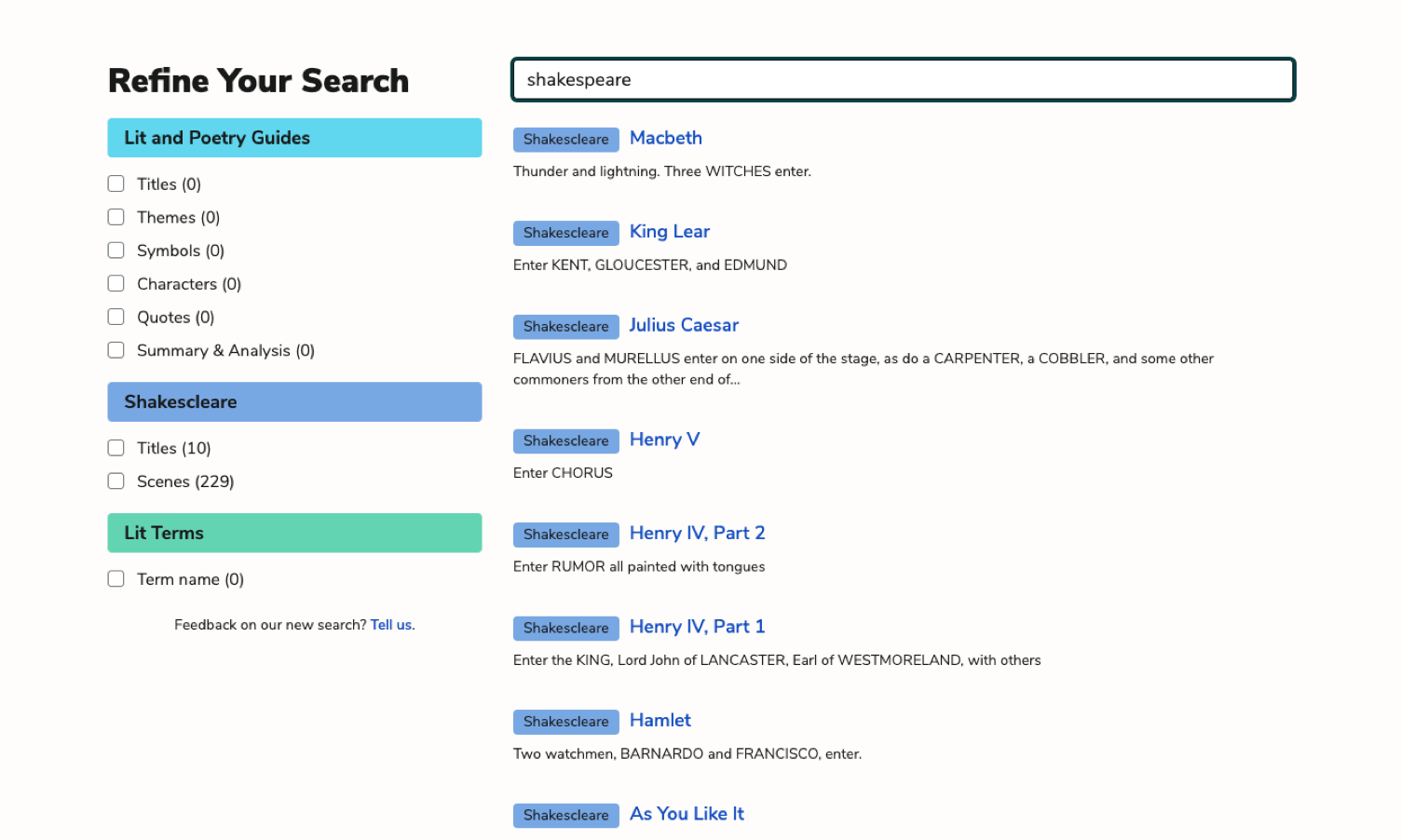

Advanced Search

Refine any search. Find related themes, quotes, symbols, characters, and more.

Poetry Guides

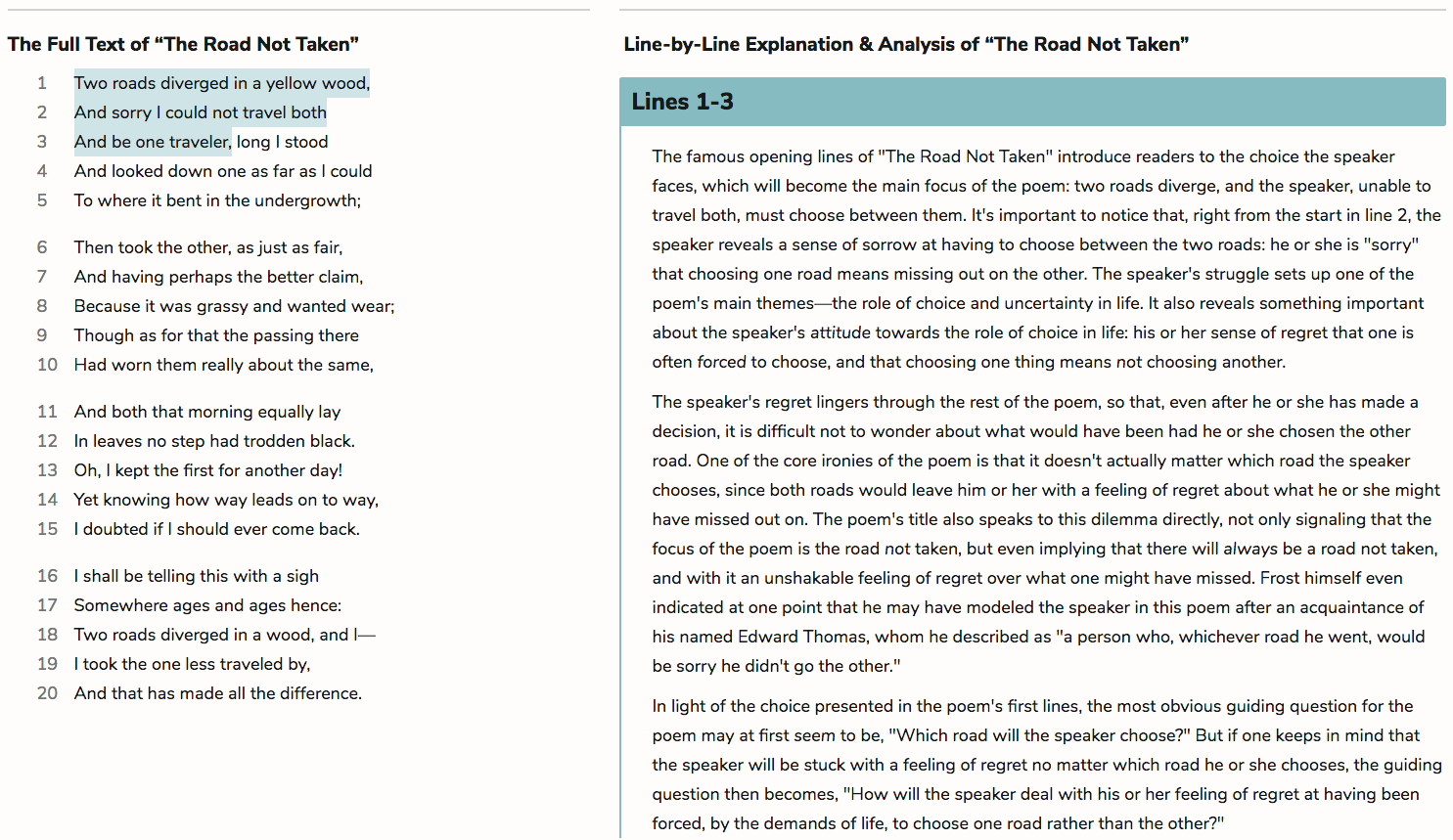

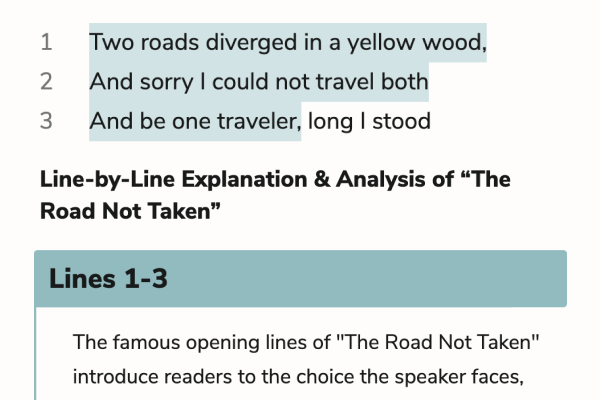

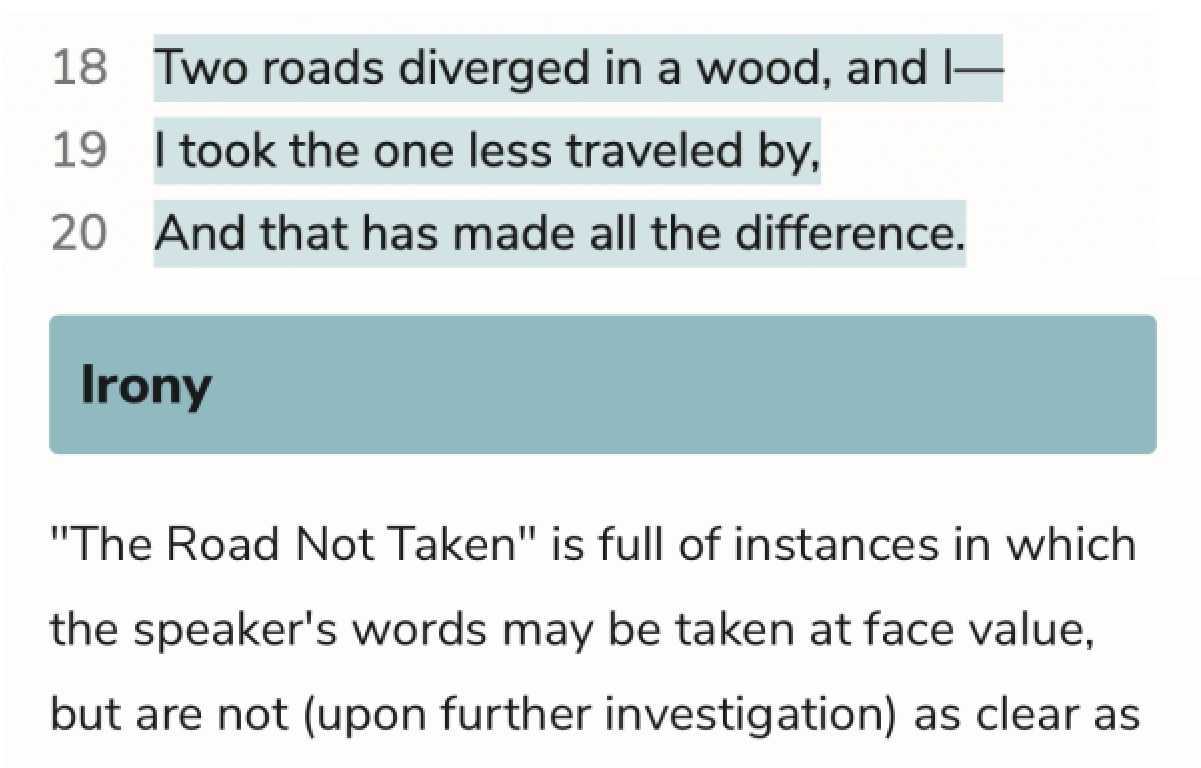

Line-by-line explanations and analysis of figurative language and poetic devices.

For every lyric poem we cover.

For every lyric poem we cover.