|

Have questions?

Contact us

Already a member? Sign in

|

Get every literary device explanation for Bleak HousePlus so much more...

Sign up for LitCharts A+Get instant access to every literary device explanation, plus so much more...

Satire

Explanation and Analysis—Nothing Sold in Chancery:

Dickens uses imagery to compare Mr. Krook's "rag and bone" shop to Lincoln's Inn in Chapter 5, drawing a direct comparison between the uselessness and disorganization of both places. When Mr. Krook explains why he is "called among the neighbors the Lord Chancellor," he says:

the neighbours think (but they know nothing), wasting away and going to rack and ruin, that that’s why they have given me and my place a christening. And I have so many old parchmentses and papers in my stock. And I have a liking for rust and must and cobwebs. And all’s fish that comes to my net. And I can’t abear to part with anything I once lay hold of (or so my neighbours think, but what do they know?) or to alter anything, or to have any sweeping, nor scouring, nor cleaning, nor repairing going on about me. That’s the way I’ve got the ill name of Chancery. I don’t mind.

Krook's neighbors call his this ramshackle establishment the "Court of Chancery" because it's as overstuffed and unproductive as Dickens's version of the Inns of Court. Referring to Mr. Krook as the "Lord Chancellor" cements the visual image of the chief lawyer himself being another old and foolish man presiding over rubbish, unable to "part with anything" or to "alter anything."

Visual images of old, dirty things pile on one another in this passage, as Krook describes his "old parchmentses and papers" and lists all the types of cleaning he will not allow. The effect Dickens's language gives is of claustrophobic, inescapable crowding and mess. This links it thematically to the very similar passage describing the "dingy," cramped, "groaning and floundering" rooms of Chancery that begins the novel.

Esther observes just before this that Krook's shop seems not to actually sell anything at all. It is just a place where "everything is bought." It doesn't do business, it just accumulates broken and useless objects:

In one part of the window was a picture of a red paper mill, at which a cart was unloading a quantity of sacks of old rags. In another, was the inscription, BONES BOUGHT. In another, KITCHEN-STUFF BOUGHT. In another, OLD IRON BOUGHT. In another, WASTE PAPER BOUGHT. In another, LADIES’ AND GENTLEMEN’S WARDROBES BOUGHT [...] pickle bottles, wine bottles, ink bottles: I am reminded by mentioning the latter, that the shop had, in several little particulars, the air of being in a legal neighbourhood, and of being, as it were, a dirty hanger-on and disowned relation of the law.

The diction of this passage is quite literally cluttered with visual images of rubbish: "sacks of old rags," "old iron," "pickle bottles," and "wine bottles" populate the writing, making a reader feel the unease and crampedness of being surrounded by garbage. Dickens's diction is also cluttered here, as can be seen in the run-on sentence that ends the passage. In describing the pandemonium of the shop, Esther's speech itself becomes messy and crowded. Her last comment contains so many clauses and nouns it's difficult to understand.

Through these thorough and visually rich descriptions of Krook's shop, Dickens adds yet another layer of satirical commentary about the mismanagement of Chancery to Bleak House. In this passage, both Lincoln's Inn and Krook's shop are merely Holborn junk emporiums filled with "waste paper."

Monthly

Annual (Best Value)

$595USD/mo

Charged $71.40 USD every year

Teacher

Teacher$795USD/mo

Charged $95.40 USD every year

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Instant PDF downloads of all 2251 LitCharts literature guides and of every new one we publish. Try a free sample literature guide.

"Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!"

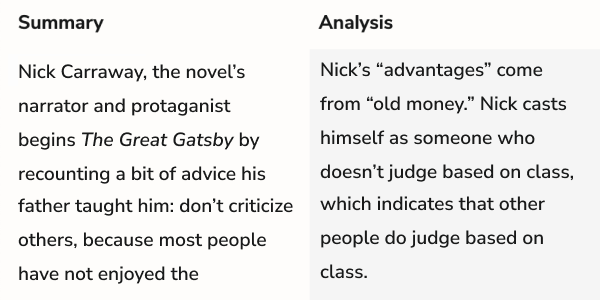

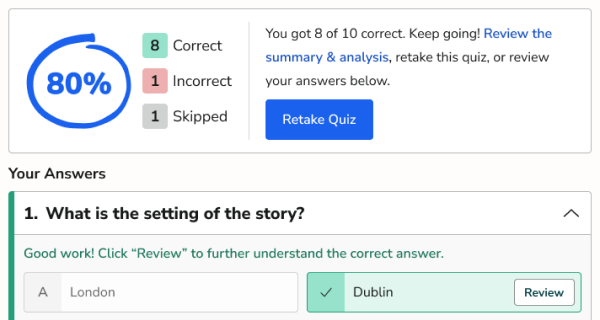

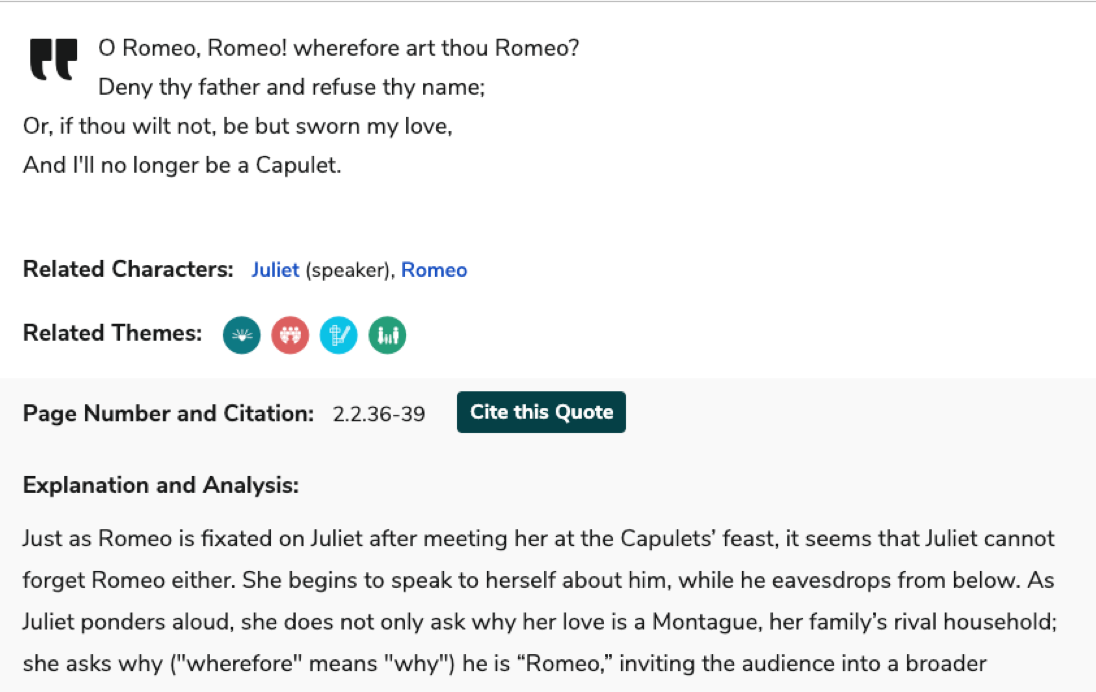

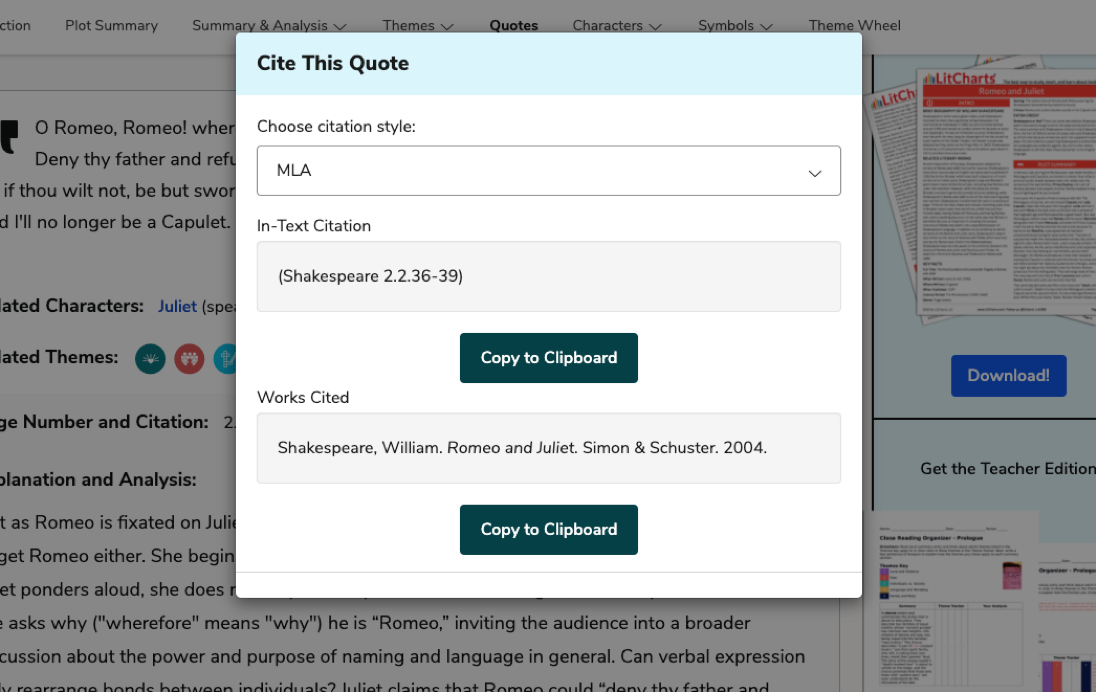

Quotes Explanations

Find the perfect quote. Understand it perfectly. Then rock the citation, too.

For all 50,202 quotes we cover.

For all 50,202 quotes we cover.

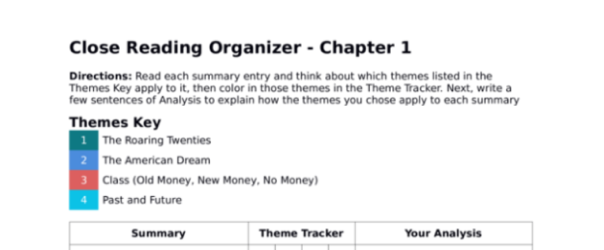

Teacher Editions

Close reading made easy for students.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

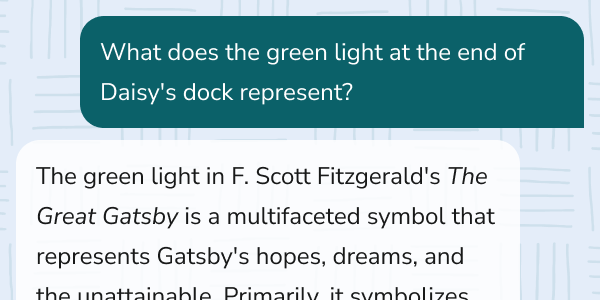

Literary Terms and Devices

Definitions and examples for every literary term and device you need to know.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Try a free sample literary term PDF.

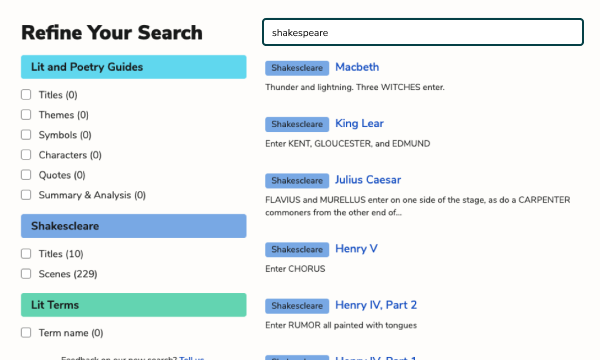

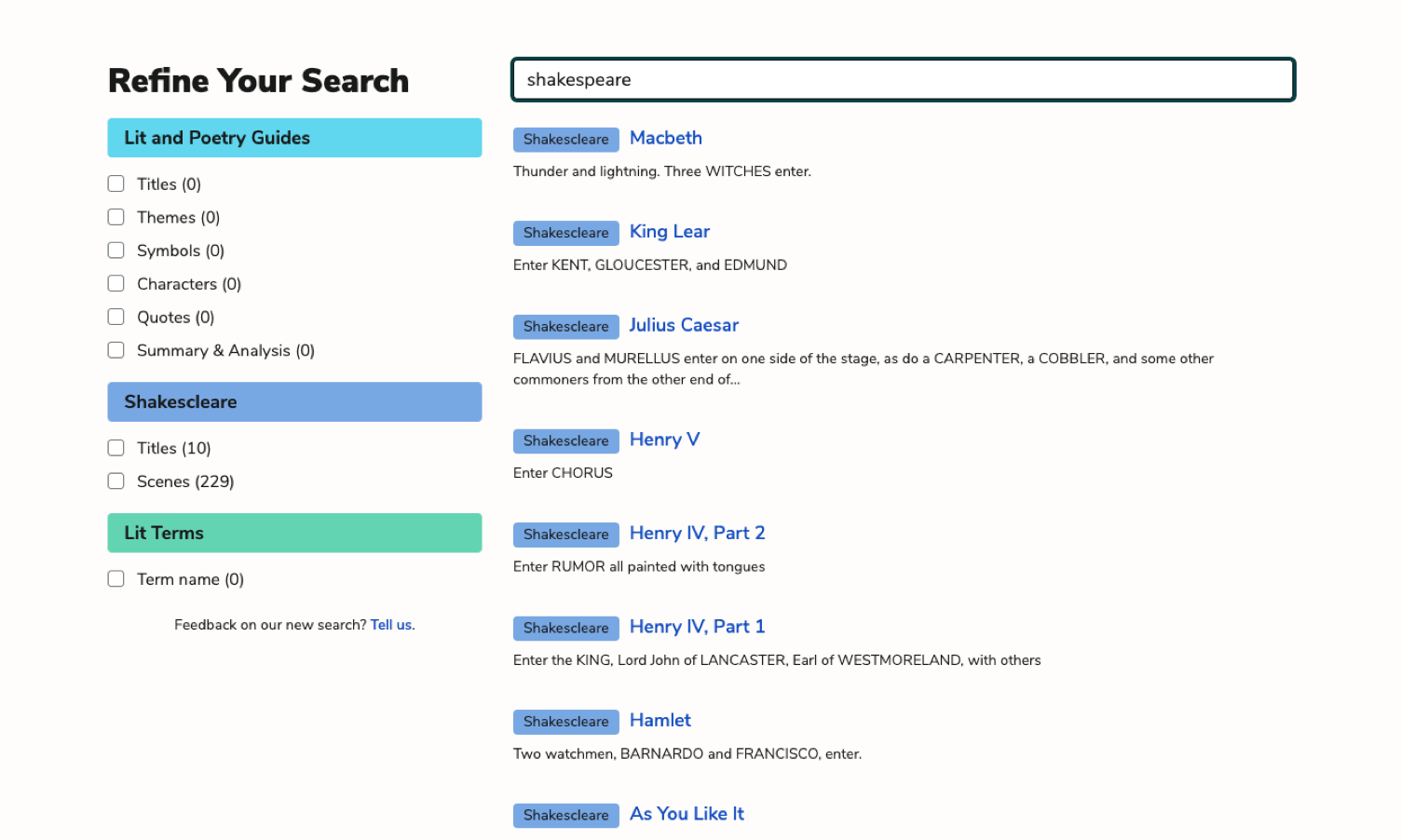

Advanced Search

Refine any search. Find related themes, quotes, symbols, characters, and more.

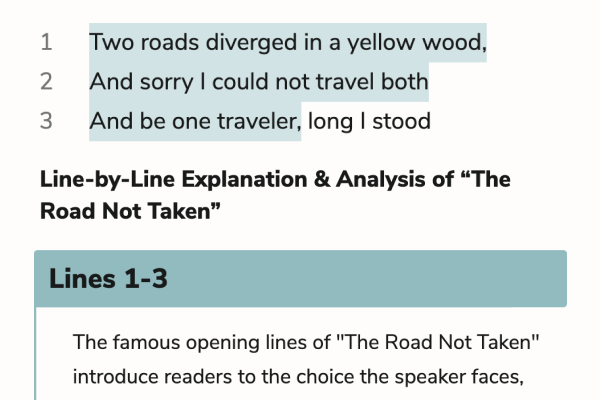

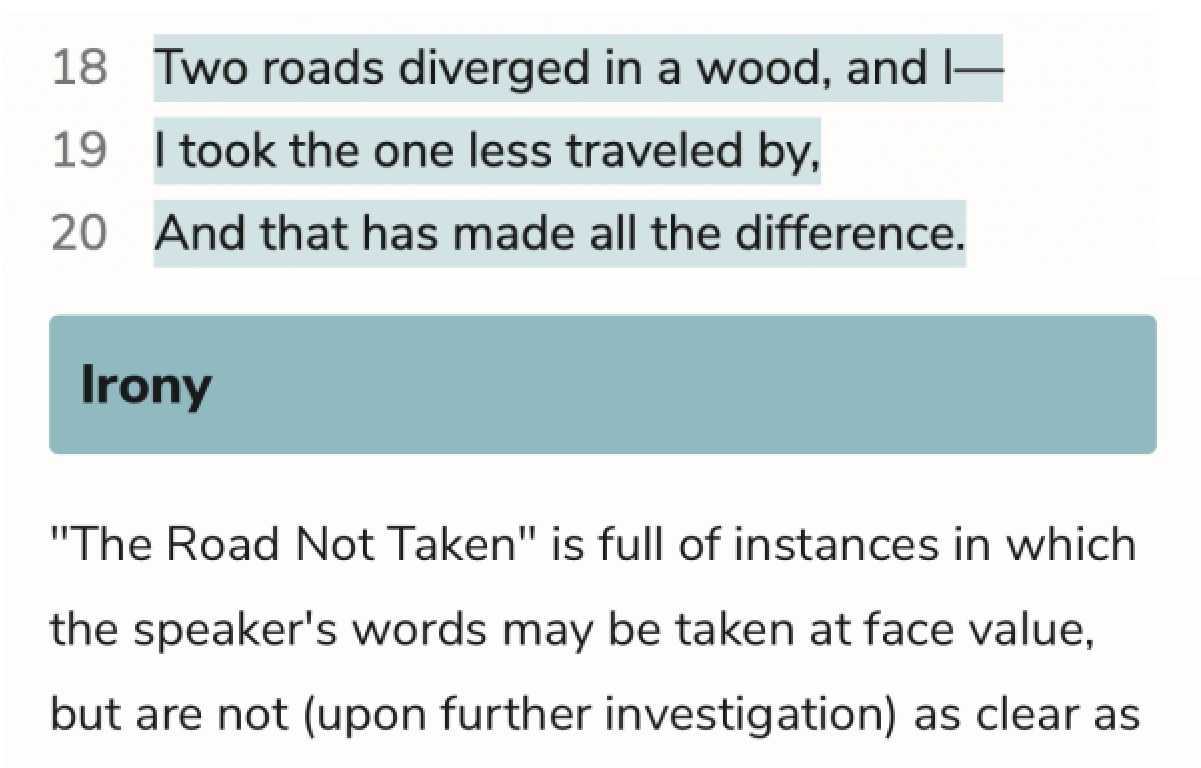

Poetry Guides

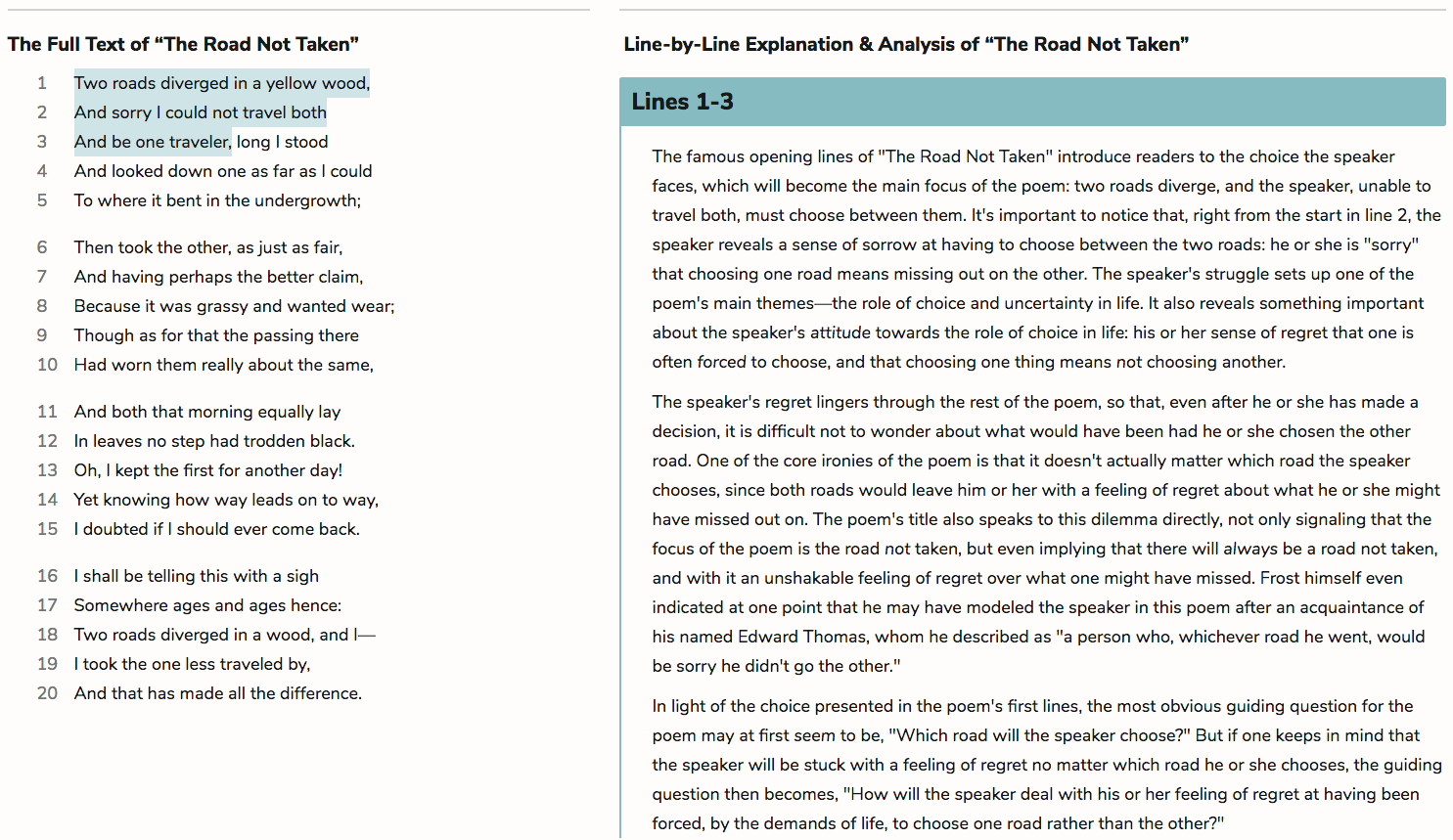

Line-by-line explanations and analysis of figurative language and poetic devices.

For every lyric poem we cover.

For every lyric poem we cover.