|

Have questions?

Contact us

Already a member? Sign in

|

Get every literary device explanation for Oliver TwistPlus so much more...

Sign up for LitCharts A+Get instant access to every literary device explanation, plus so much more...

Satire

Explanation and Analysis—Poor Laws:

Throughout the novel, Dickens uses the ironic tone of the narrator to satirize English laws for dealing with poverty, especially the Poor Law of 1834. An early instance of this satire occurs in chapter 2, which describes Oliver's infancy under this law:

[Oliver is] despatched to a branch-workhouse some three miles off, where twenty or thirty other juvenile offenders against the poor-laws rolled about the floor all day, without the inconvenience of too much food, or too much clothing, under the parental superintendence of an elderly female who received the culprits at and for the consideration of sevenpence-halfpenny per small head per week.

In reality, the woman siphons off most of the money for herself, starving the children under the pretense that it is bad for them to be overfed or coddled. The Poor Law of 1834 consolidated poor people in workhouses. It aimed both to reduce the state cost of supporting poor people and to encourage poor people to work for a living rather than relying on the state. The passage describing Oliver's entry into this system uses humor to demonstrate that it not only failed poor children and adults, but in fact made them targets of people like this woman, who "serves" Oliver and the other children by saving them from the "inconvenience" of life-sustaining nutrition. In Chapter 12, when Mrs. Bedwin is feeding Oliver, it becomes apparent just how much these children are being starved:

And with this, the old lady applied herself to warming up in a little saucepan a basin full of broth strong enough to furnish an ample dinner, when reduced to the regulation strength, for three hundred and fifty paupers, at the very lowest computation.

The narrator is no doubt exaggerating for comedic effect, but Dickens also sets up the reader to be alarmed. How on earth could a single saucepan of broth, intended for one little boy by a woman who actually wants to nurture him, stretch to feed 350 people? It must be barely more than water at that point. No wonder Oliver asks for more food when he is living in the workhouse.

Dickens uses not only the narrator, but also certain characters' comments to satirize the Poor Laws. In Chapter 19, Sikes laments his loss of a chimney sweep whom he used to employ to slip through small spaces for robberies:

But the father gets lagged, and then the Juvenile Delinquent Society comes, and takes the boy away from a trade where he was arning money, teaches him to read and write, and in time makes a ‘prentice of him.

Although the idea of training a child in an honest trade so that he will stop breaking into houses sounds good, Sikes actually has a point. Readers have seen what happened to Oliver when he was apprenticed with Mr. Sowerberry. Breaking up a family by arresting the parent and placing the child with a master of trade might not produce a better outcome for that child at all. The fact that Sikes—one of the novel's villains—makes a reasonable point emphasizes just how bad the Poor Laws are: even a villain can see that they don't work, and even an apprenticeship to a villain might be better than some standard apprenticeships.

Monthly

Annual (Best Value)

$595USD/mo

Charged $71.40 USD every year

Teacher

Teacher$795USD/mo

Charged $95.40 USD every year

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Instant PDF downloads of all 2250 LitCharts literature guides and of every new one we publish. Try a free sample literature guide.

"Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!"

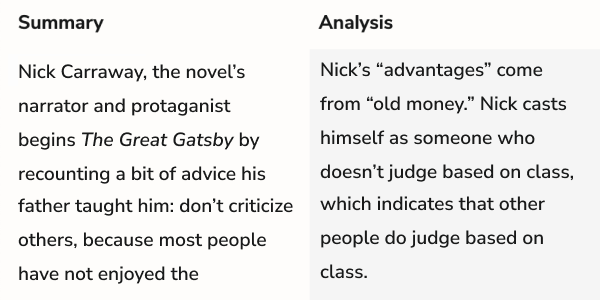

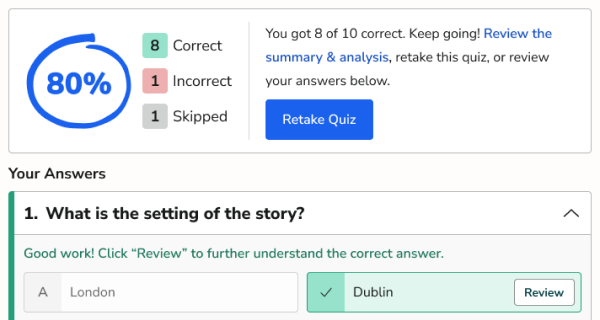

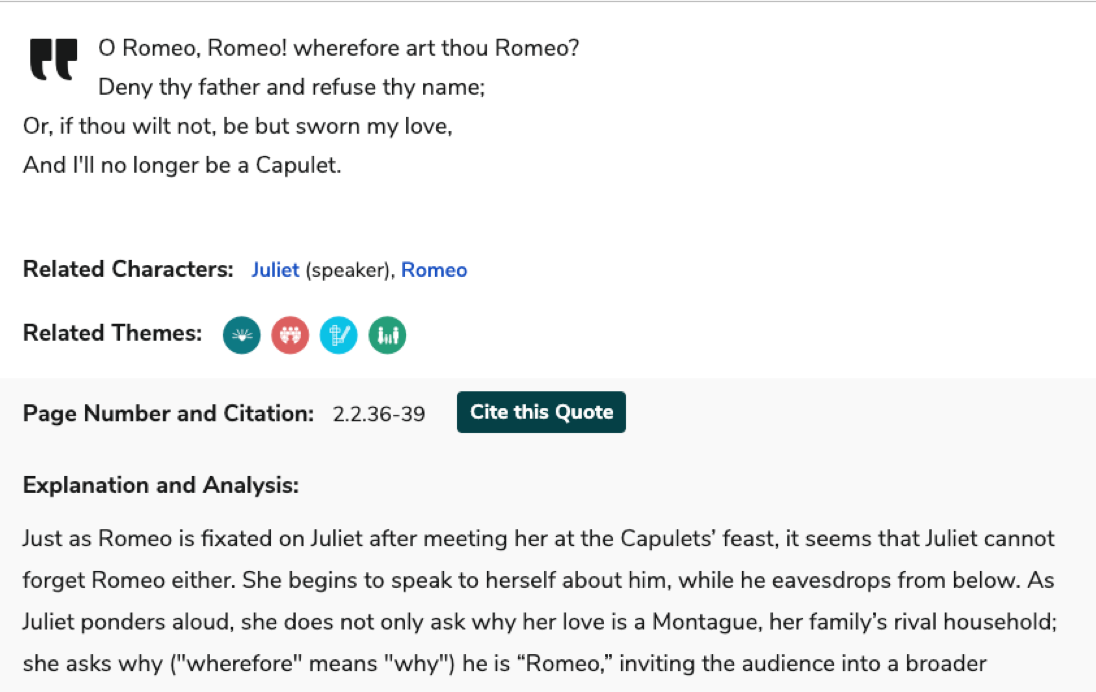

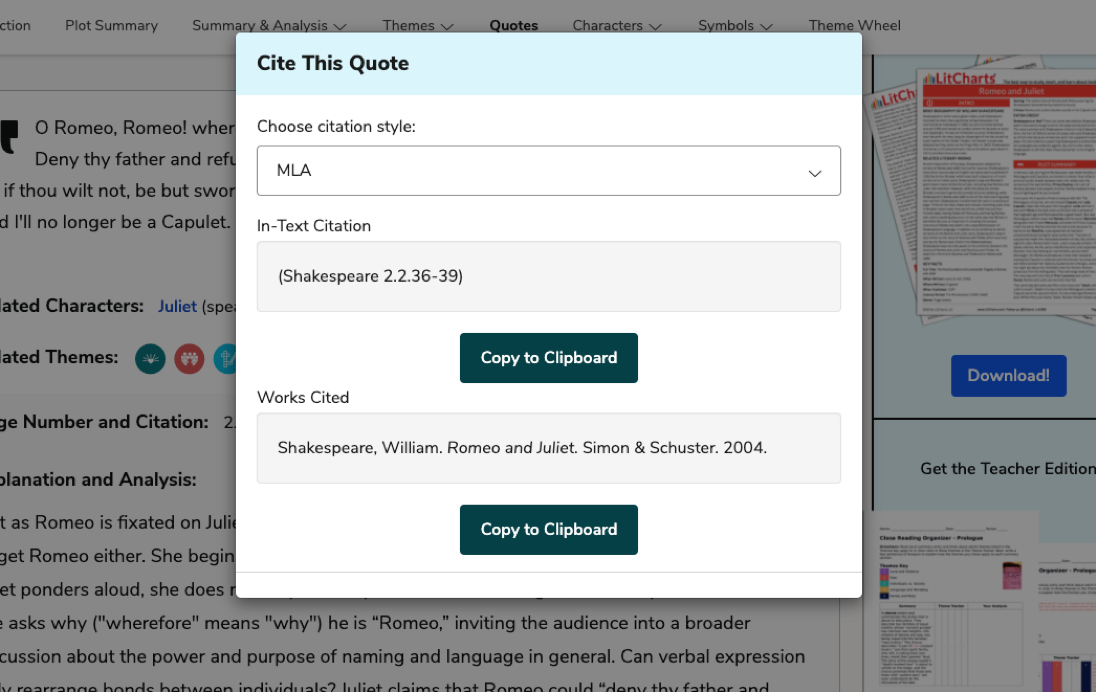

Quotes Explanations

Find the perfect quote. Understand it perfectly. Then rock the citation, too.

For all 50,177 quotes we cover.

For all 50,177 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

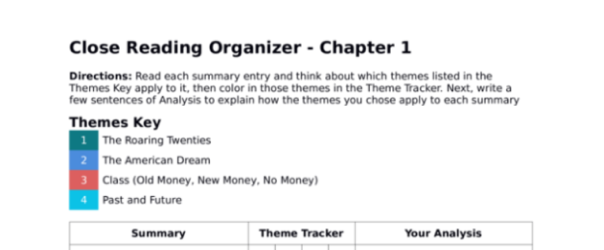

Close reading made easy for students.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

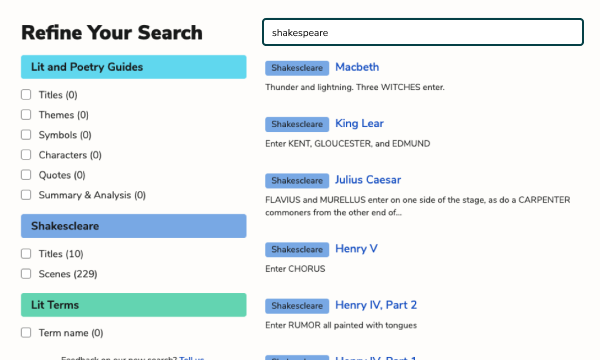

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

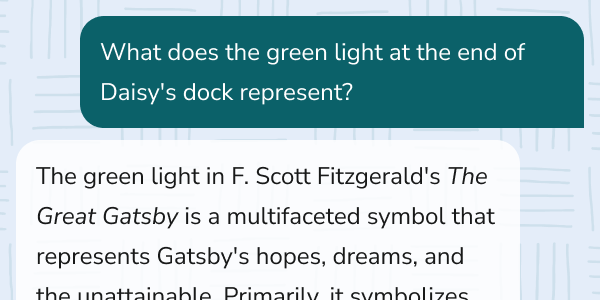

Literary Terms and Devices

Definitions and examples for every literary term and device you need to know.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Try a free sample literary term PDF.

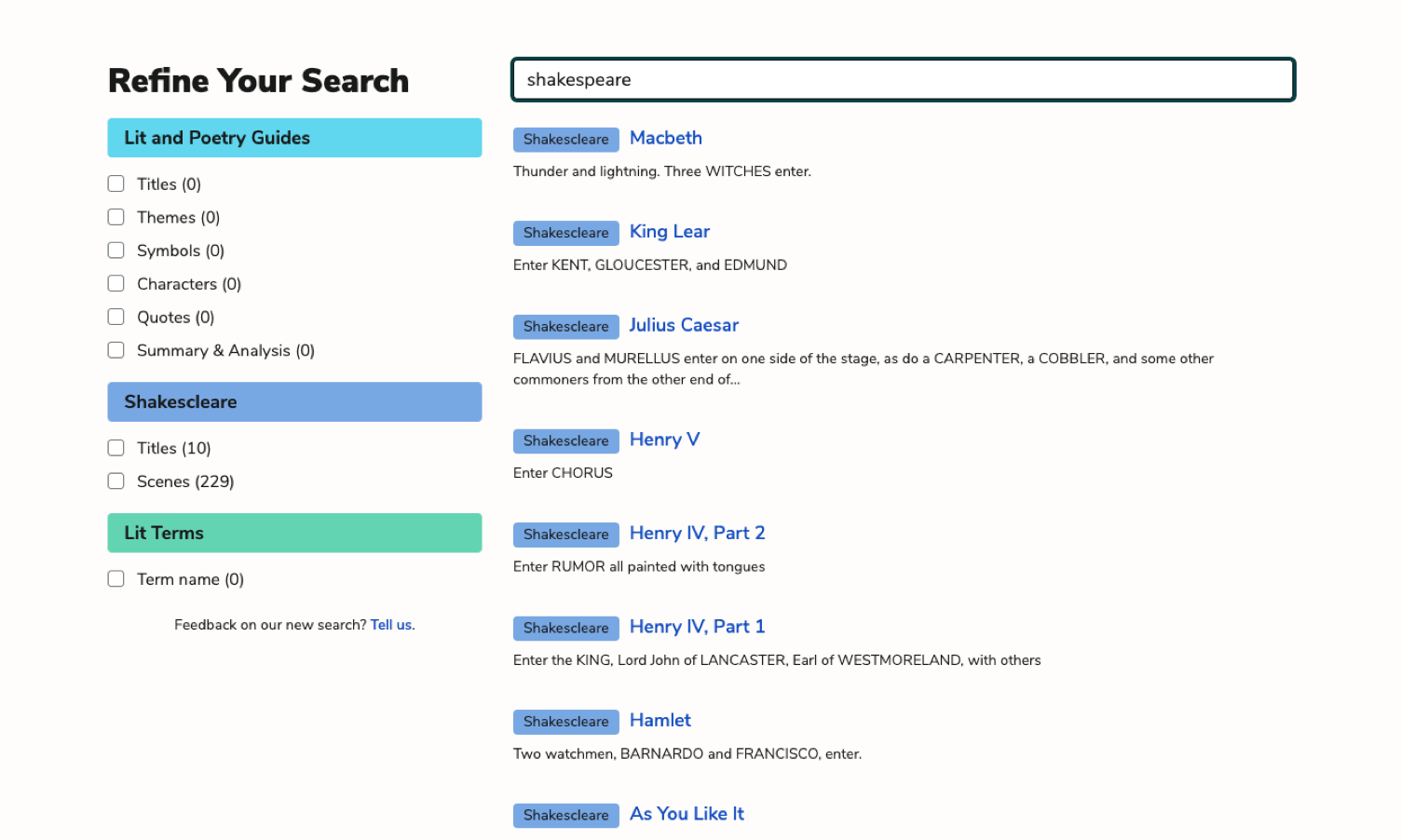

Advanced Search

Refine any search. Find related themes, quotes, symbols, characters, and more.

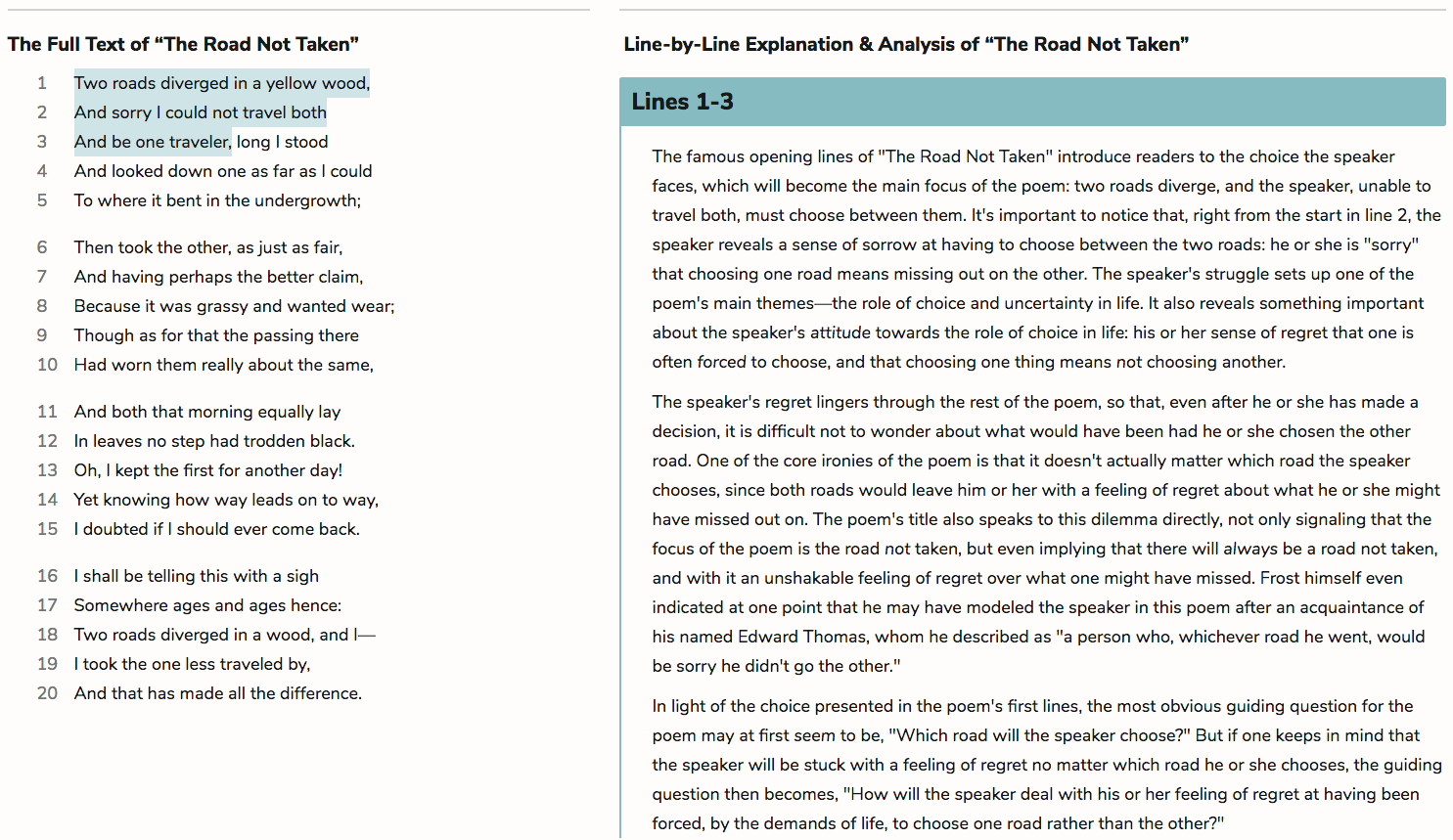

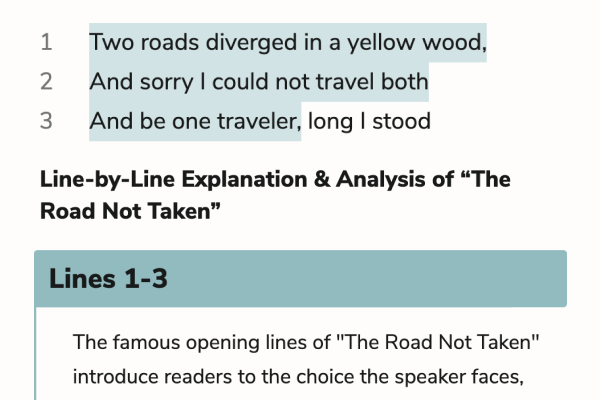

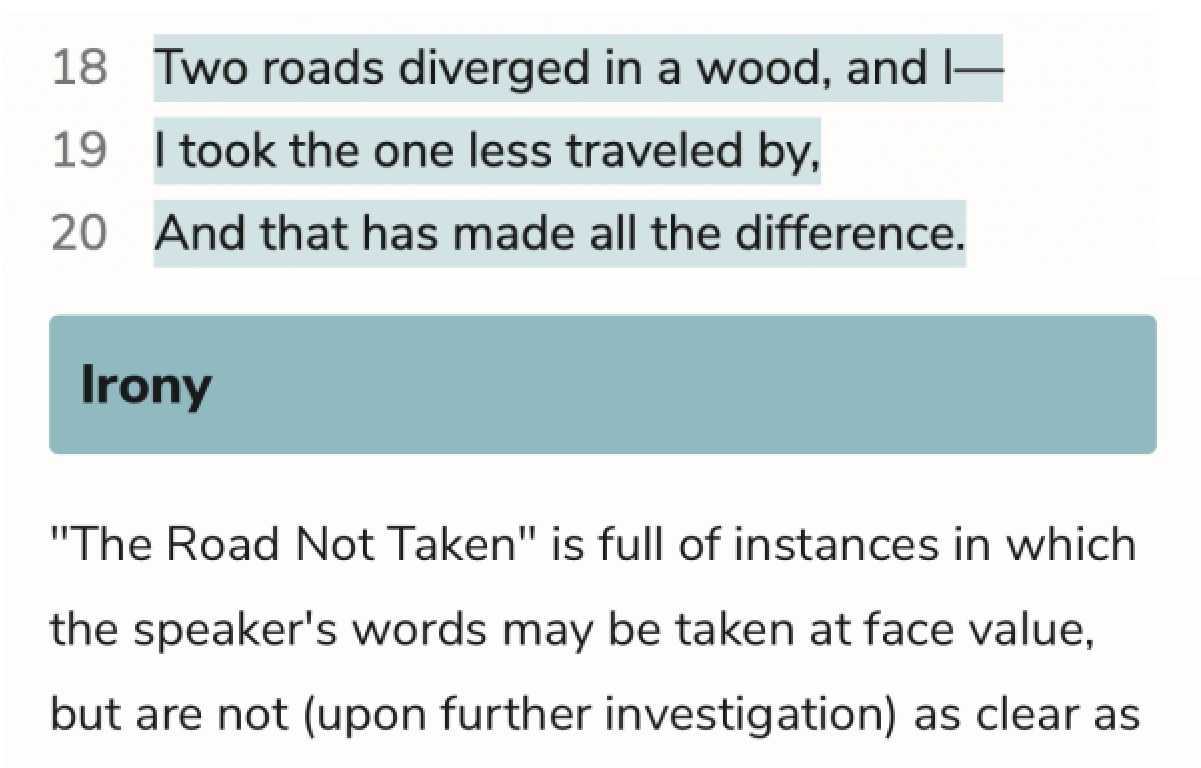

Poetry Guides

Line-by-line explanations and analysis of figurative language and poetic devices.

For every lyric poem we cover.

For every lyric poem we cover.