|

|

Have questions?

Contact us

Already a member? Sign in

|

Get every literary device explanation for Death in VenicePlus so much more...

Sign up for LitCharts A+Get instant access to every literary device explanation, plus so much more...

Simile

Explanation and Analysis—Inexpressive as a God :

As Aschenbach watches Tadzio at the beach, he observes the young boy look upon a loud Russian family with undisguised hostility and irritation. In his reflections, Aschenbach compares Tadzio, in a simile, to a god:

But he was exhilarated and shaken at the same time—in a word, he was in bliss. Through this childish fanaticism directed against that totally good-natured segment of life, what had been as inexpressive as a god was placed within a human relationship; a precious artefact of nature, which had served only as a feast for the eyes, now appeared worthy of a deeper rapport; and the figure of the adolescent, already significant for its beauty, was now set off against a background that made it possible to take him seriously beyond his years.

Aschenbach is, at first, surprised to see Tadzio's aggressive expression, as the boy usually appears polite and mild-mannered. He feels simultaneously "exhilarated and shaken" to see this "childish fanaticism directed against that totally good-natured segment of life," concluding that Tadzio, previously "as inexpressive as a god," was now "placed within a human relationship." Previously, Aschenbach had looked upon Tadzio as if he were a sculpture of a young god, regarding him as remote, cold, and inhuman. When he sees the boy's transparent annoyance, however, he looks upon him, for the first time, as a human coexisting among other humans.

Rather than breaking the spell of Aschenbach's obsession, Aschenbach now feels that Tadzio is "worthy of an even deeper rapport," as he combines, for Aschenbach, both human and godlike traits. Throughout the novel, Aschenbach tends to treat Tadzio more as an ideal than an actual child, perceiving him through the lens of Ancient Greek art and mythology.

Monthly

Annual (Best Value)

$595USD/mo

Charged $71.40 USD every year

Teacher

Teacher$795USD/mo

Charged $95.40 USD every year

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Instant PDF downloads of all 2238 LitCharts literature guides and of every new one we publish. Try a free sample literature guide.

"Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!"

Quotes Explanations

Find the perfect quote. Understand it perfectly. Then rock the citation, too.

For all 49,909 quotes we cover.

For all 49,909 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

Close reading made easy for students.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

Literary Terms and Devices

Definitions and examples for every literary term and device you need to know.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Try a free sample literary term PDF.

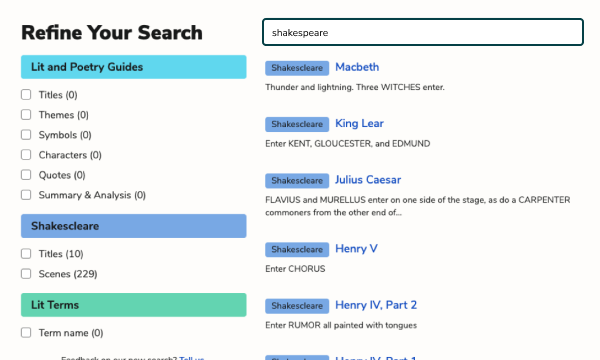

Advanced Search

Refine any search. Find related themes, quotes, symbols, characters, and more.

Poetry Guides

Line-by-line explanations and analysis of figurative language and poetic devices.

For every lyric poem we cover.

For every lyric poem we cover.