|

Have questions?

Contact us

Already a member? Sign in

|

Get every literary device explanation for White FangPlus so much more...

Sign up for LitCharts A+Get instant access to every literary device explanation, plus so much more...

Simile

Explanation and Analysis—White Fang as a Plant:

In Part 2, Chapter 3, London uses a simile to compare White Fang and his siblings to plants moving toward the light that shines through the entrance of the cave they were born in:

The life of his body and every fiber of his body, the life that was the very substance of his body and that was apart from his own personal life, had yearned toward this light and urged his body toward it in the same way the cunning chemistry of a plant urges it toward the sun […] The light drew [the pups] as if they were plants; the chemistry of life that composed them demanded the light as a necessity of being; and their little puppet-bodies crawled blindly and mechanically, like the tendrils of a vine.

Throughout the novel, light is a symbol that represents the will for life and growth inherent within all living things. White Fang’s initial movement toward the light as a puppy represents his will to live, thrive, and grow. This will is not conscious but instinctual and closely associated with White Fang’s deep connection to the wilderness, which at several points in the novel is metaphorically represented as “roots” connecting him to his origins in the Wild. That this will to life is described in the above passage as something “apart from his own personal life” suggests that it is not his individual will, but rather nature’s will existing within all living things and urging them toward growth and movement. London’s choice to compare White Fang to a plant also reflects this, because plants don’t have conscious will—they grow toward the sun automatically, driven by an external force larger than themselves.

In Part 5, Chapter 4, when White Fang has been living on Weedon Scott’s estate for several months and is settling into his new life of comfort and domestication, London uses another simile to compare White Fang to a plant, only this time, he describes him as being like a flower rather than the wild “tendrils of a vine:”

There was plenty of food and no work in the Southland, and White Fang lived fat and prosperous and happy. Not alone was he in the geographical Southland, for he was also in the Southland of life. Human kindness was like a sun shining upon him, and he flourished like a flower planted in good soil.

The effect of this second simile is twofold. First, it expresses that White Fang’s nature has by this point in the novel “flowered,” meaning that its innate potential, originally cramped and stunted in its growth by cruelty and struggle, has been fully realized under the kindness and love of Weedon Scott. Second, it reveals that the “roots” connecting him back to the Wild have finally been severed, meaning that he is by this point in the novel completely domesticated—he’s gone from being like a tree rooted in the forest to being like a potted plant, healthier from being watered and tended to by his human masters, but no longer planted in the soil of the wilderness. This simile reveals the complexity of White Fang’s domestication. While on the one hand he is happier and safer as Weedon Scott’s pet, on the other, much of his strength when he was young came from his deep connection to the wilderness, and the severing of his wild roots represents the loss of this primal strength as well as his freedom. By submitting to the mastery of humans, White Fang gives up as much as he gains.

Monthly

Annual (Best Value)

$595USD/mo

Charged $71.40 USD every year

Teacher

Teacher$795USD/mo

Charged $95.40 USD every year

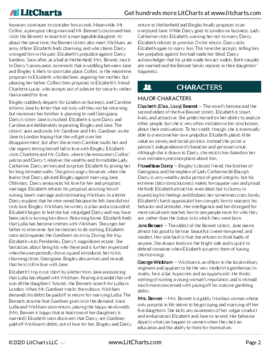

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Instant PDF downloads of all 2252 LitCharts literature guides and of every new one we publish. Try a free sample literature guide.

"Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!"

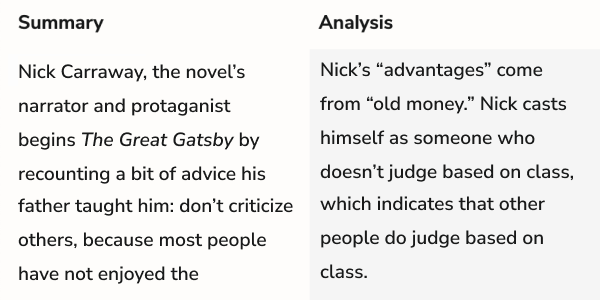

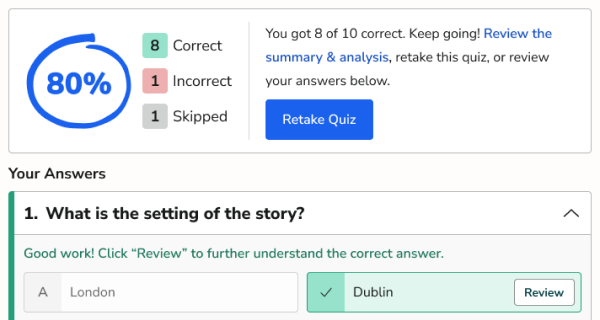

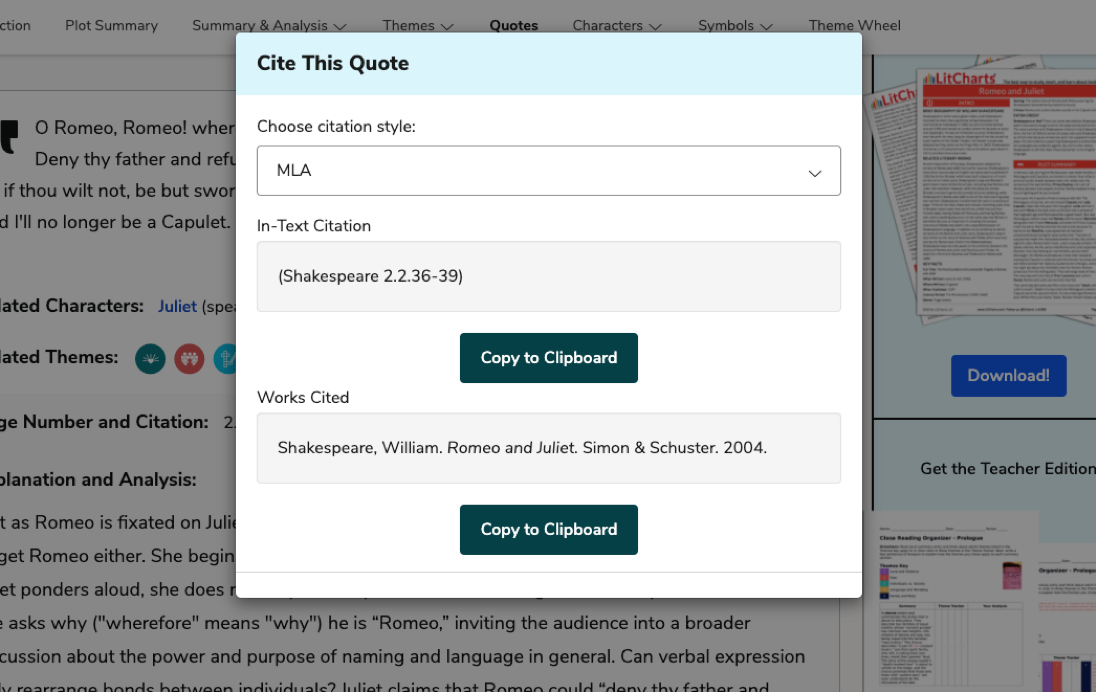

Quotes Explanations

Find the perfect quote. Understand it perfectly. Then rock the citation, too.

For all 50,213 quotes we cover.

For all 50,213 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

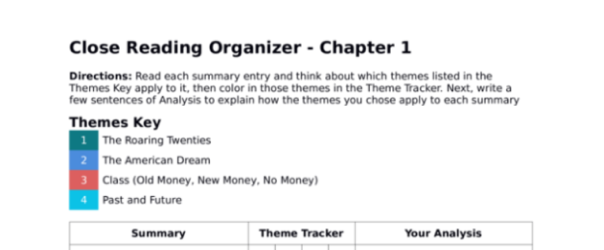

Close reading made easy for students.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

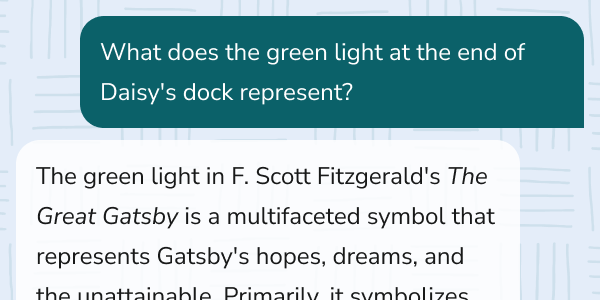

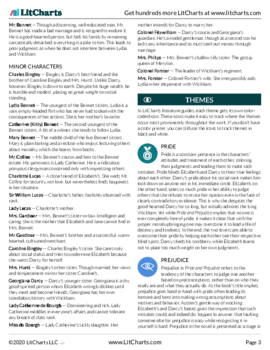

Literary Terms and Devices

Definitions and examples for every literary term and device you need to know.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Try a free sample literary term PDF.

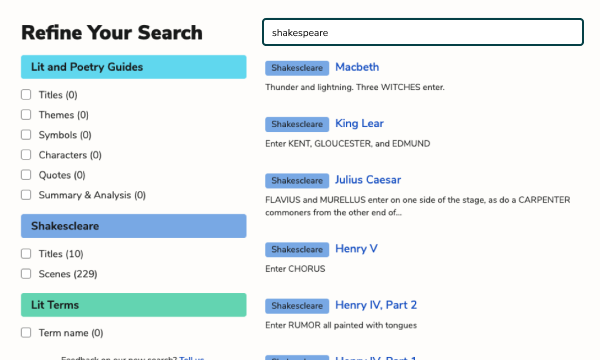

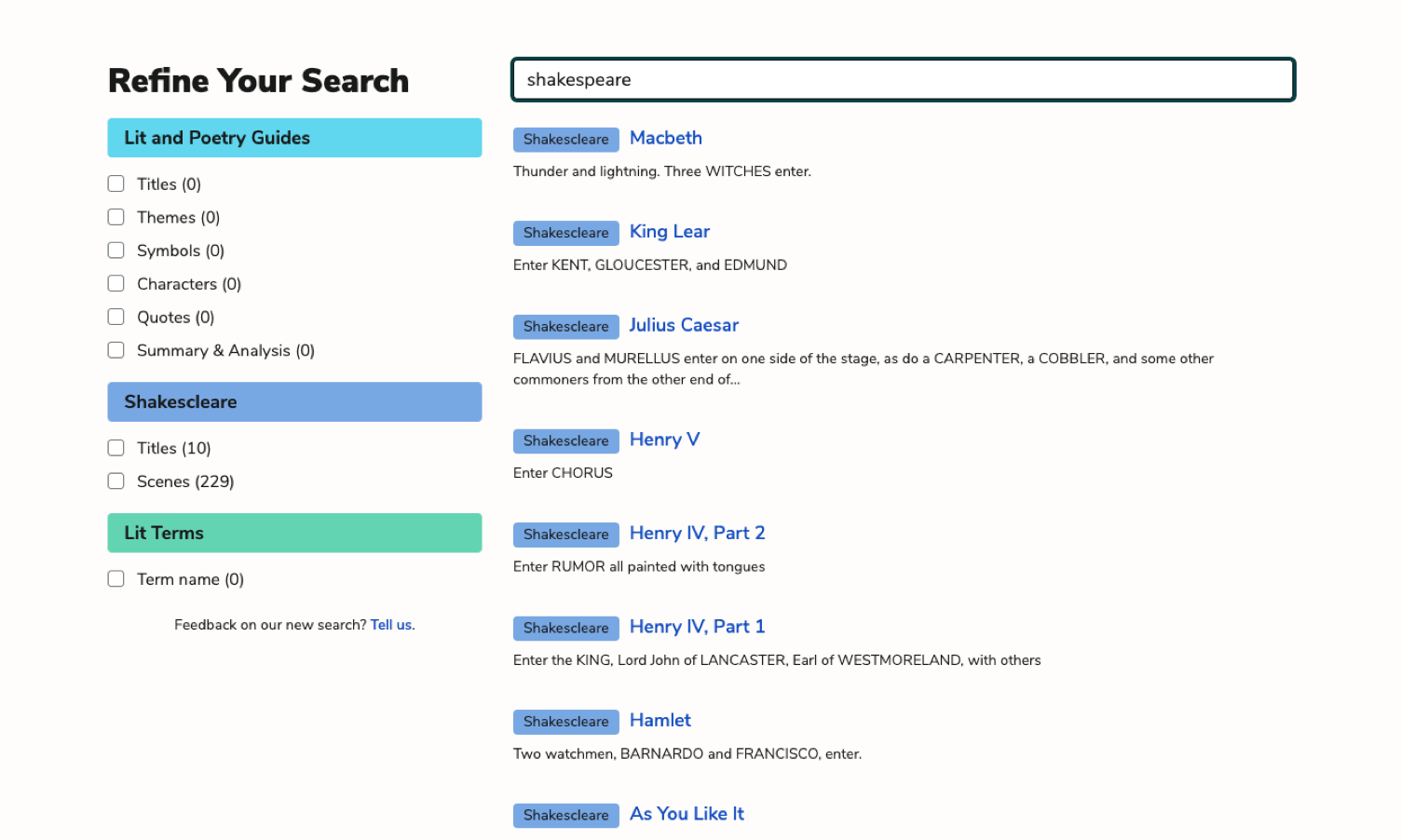

Advanced Search

Refine any search. Find related themes, quotes, symbols, characters, and more.

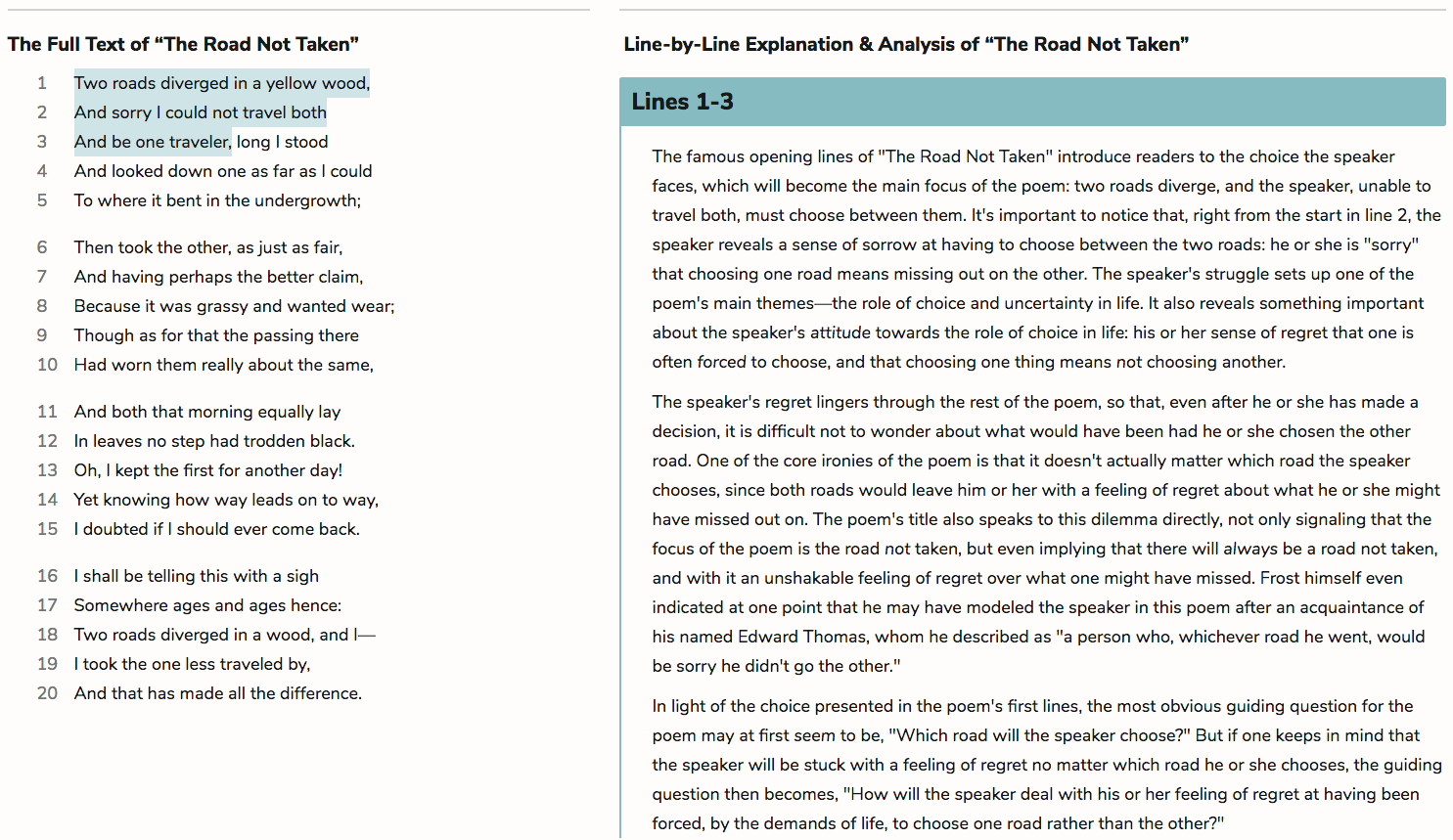

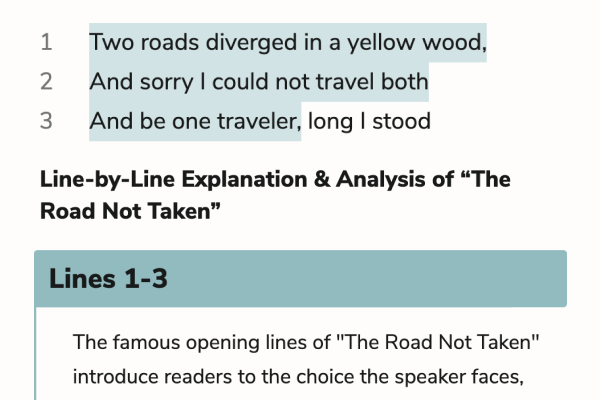

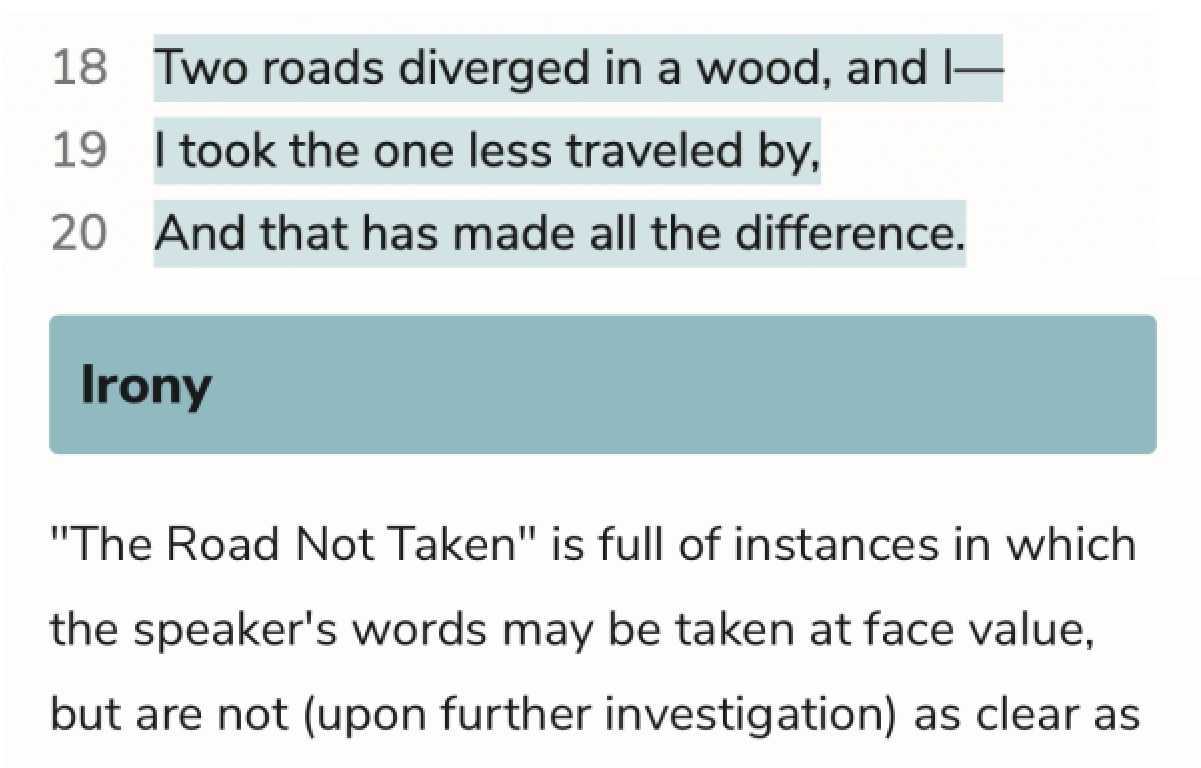

Poetry Guides

Line-by-line explanations and analysis of figurative language and poetic devices.

For every lyric poem we cover.

For every lyric poem we cover.