|

Have questions?

Contact us

Already a member? Sign in

|

Get every quote explanation for The French Lieutenant’s WomanPlus so much more...

Sign up for LitCharts A+Get instant access to every quote explanation for The French Lieutenant’s Woman, plus so much more...

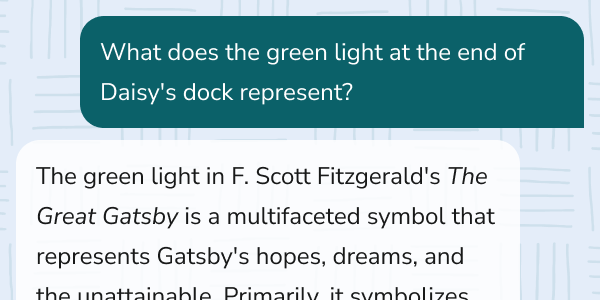

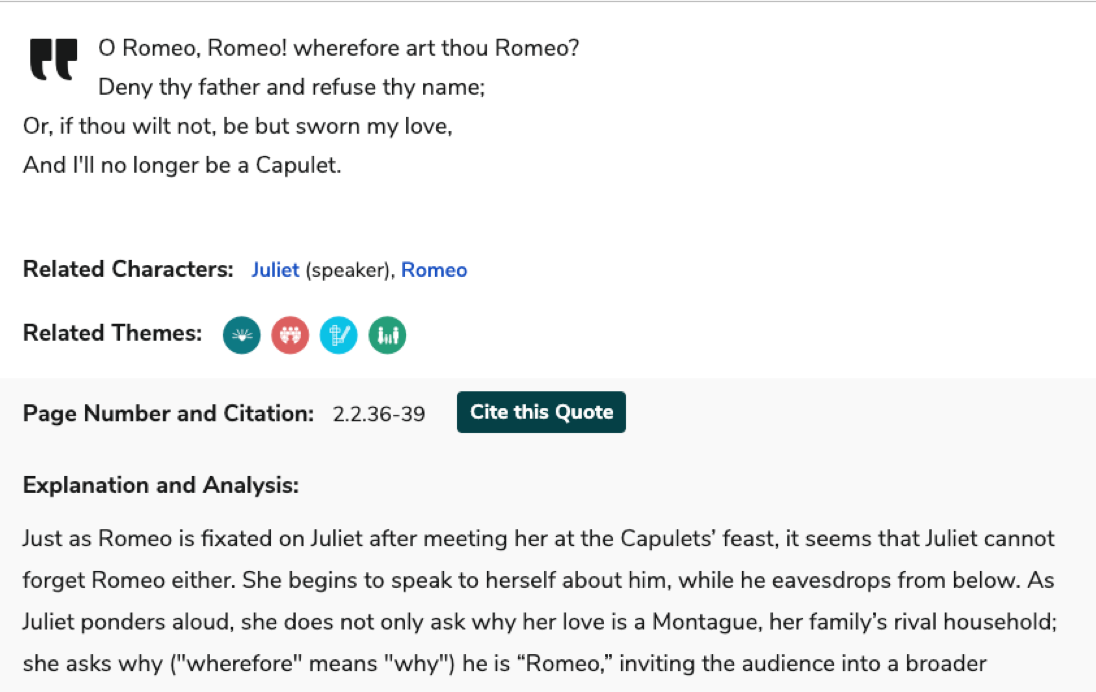

Explanation and Analysis:

As Charles travels to London on the train, the narrator sits down opposite him and contemplates where to take the story from here, and what the ending should be. In this passage, he discusses the literary practice of using the plot of a story t...

Monthly

Annual (Best Value)

$595USD/mo

Charged $71.40 USD every year

Teacher

Teacher$795USD/mo

Charged $95.40 USD every year

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Instant PDF downloads of all 2251 LitCharts literature guides and of every new one we publish. Try a free sample literature guide.

"Would not have made it through AP Literature without the printable PDFs. They're like having in-class notes for every discussion!"

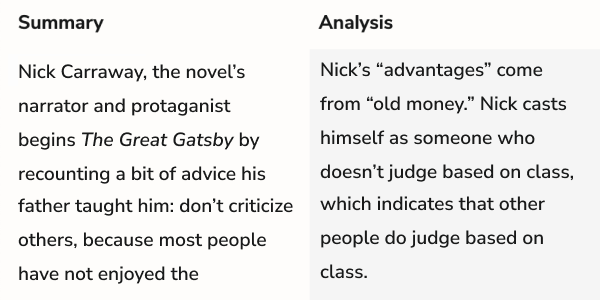

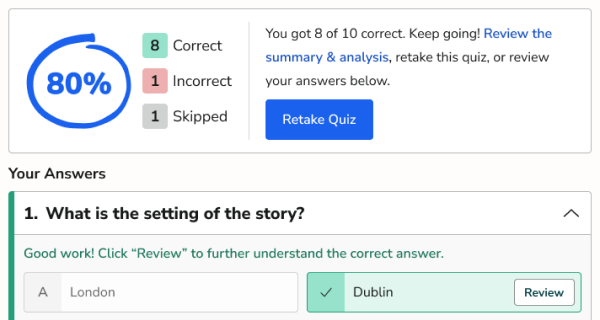

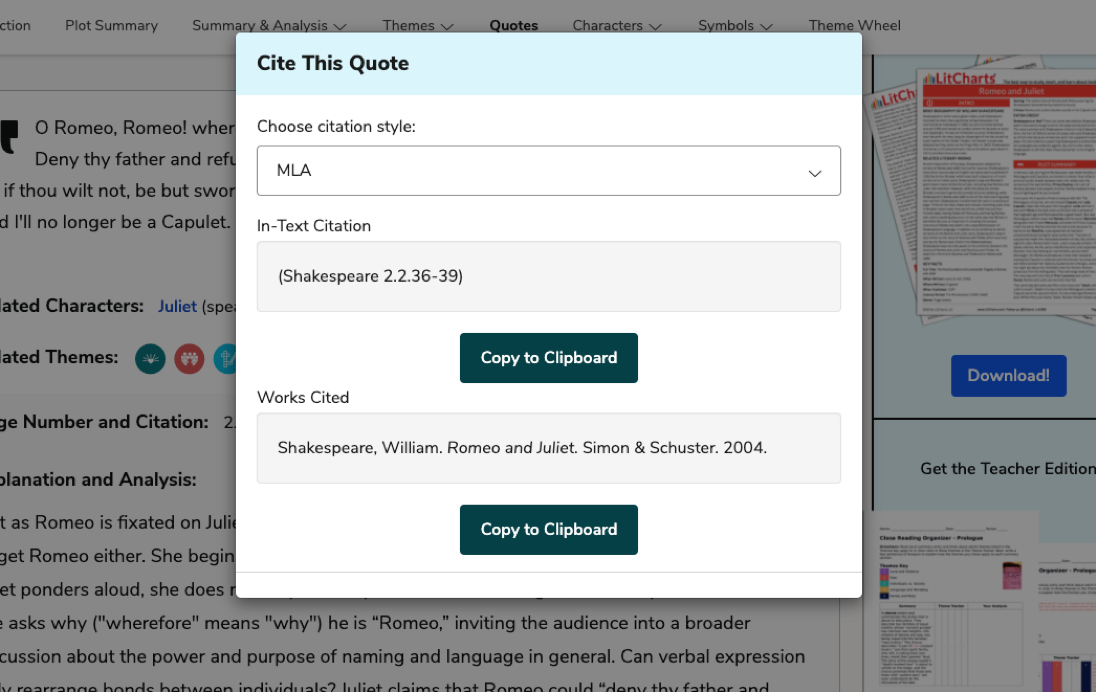

Quotes Explanations

Find the perfect quote. Understand it perfectly. Then rock the citation, too.

For all 50,202 quotes we cover.

For all 50,202 quotes we cover.

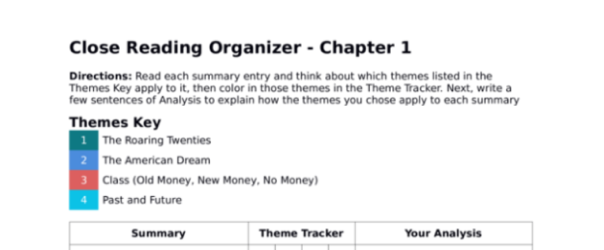

Teacher Editions

Close reading made easy for students.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

Literary Terms and Devices

Definitions and examples for every literary term and device you need to know.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.

Try a free sample literary term PDF.

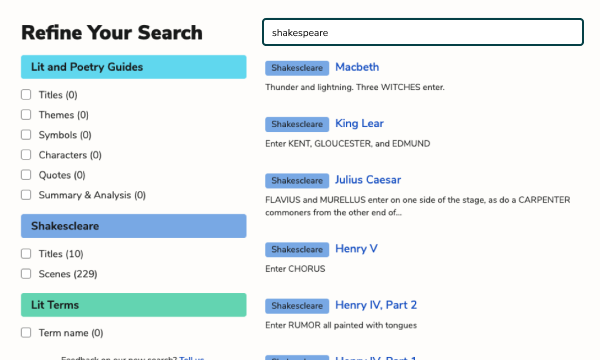

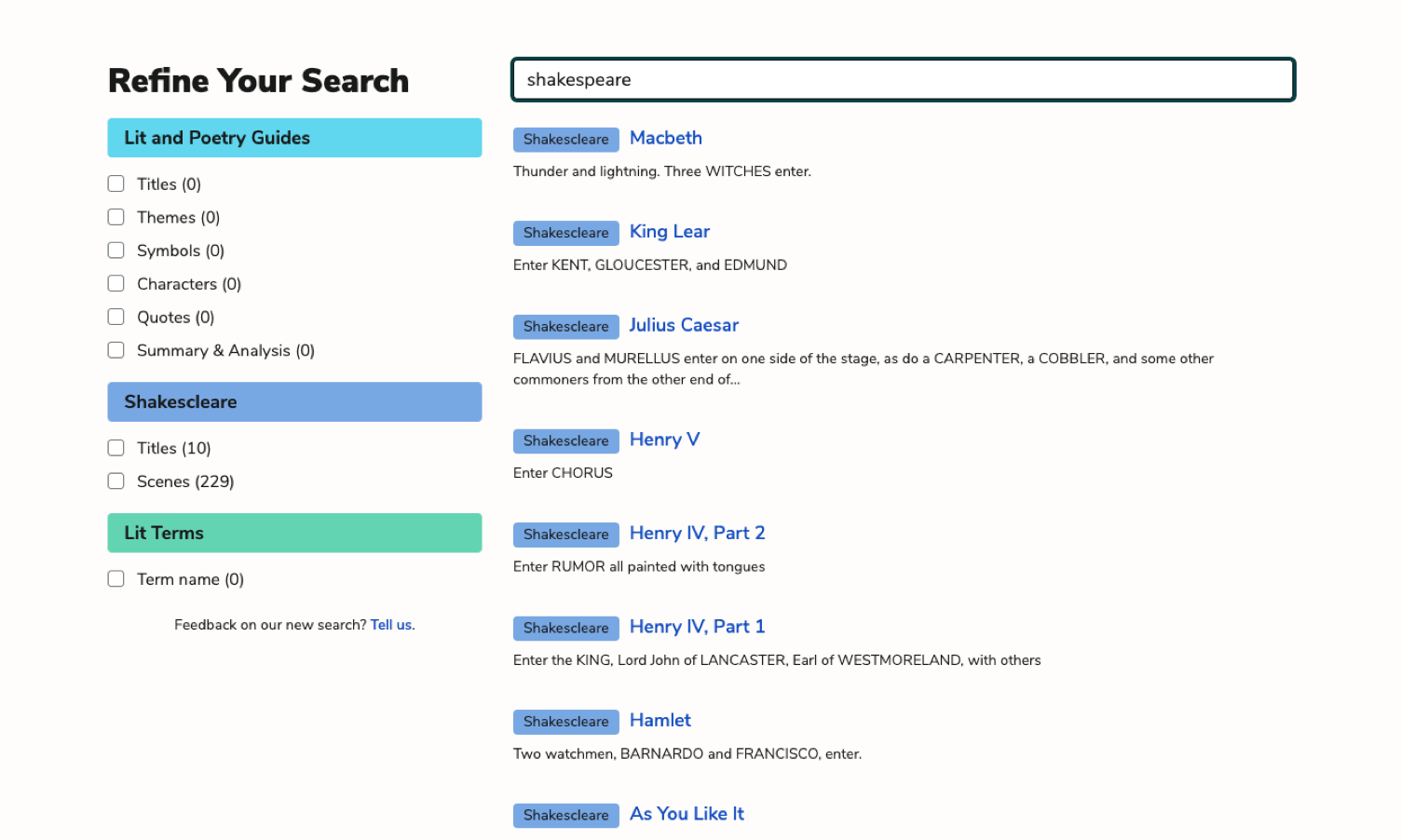

Advanced Search

Refine any search. Find related themes, quotes, symbols, characters, and more.

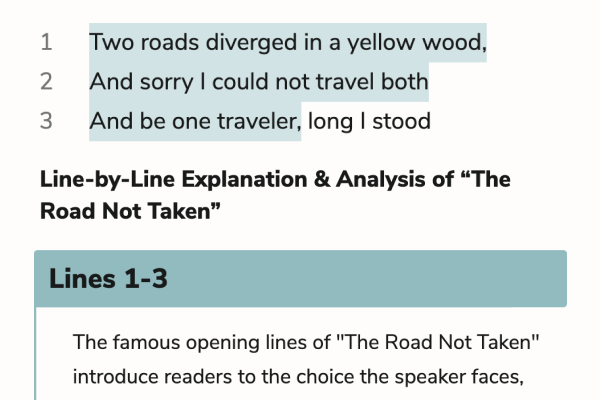

Poetry Guides

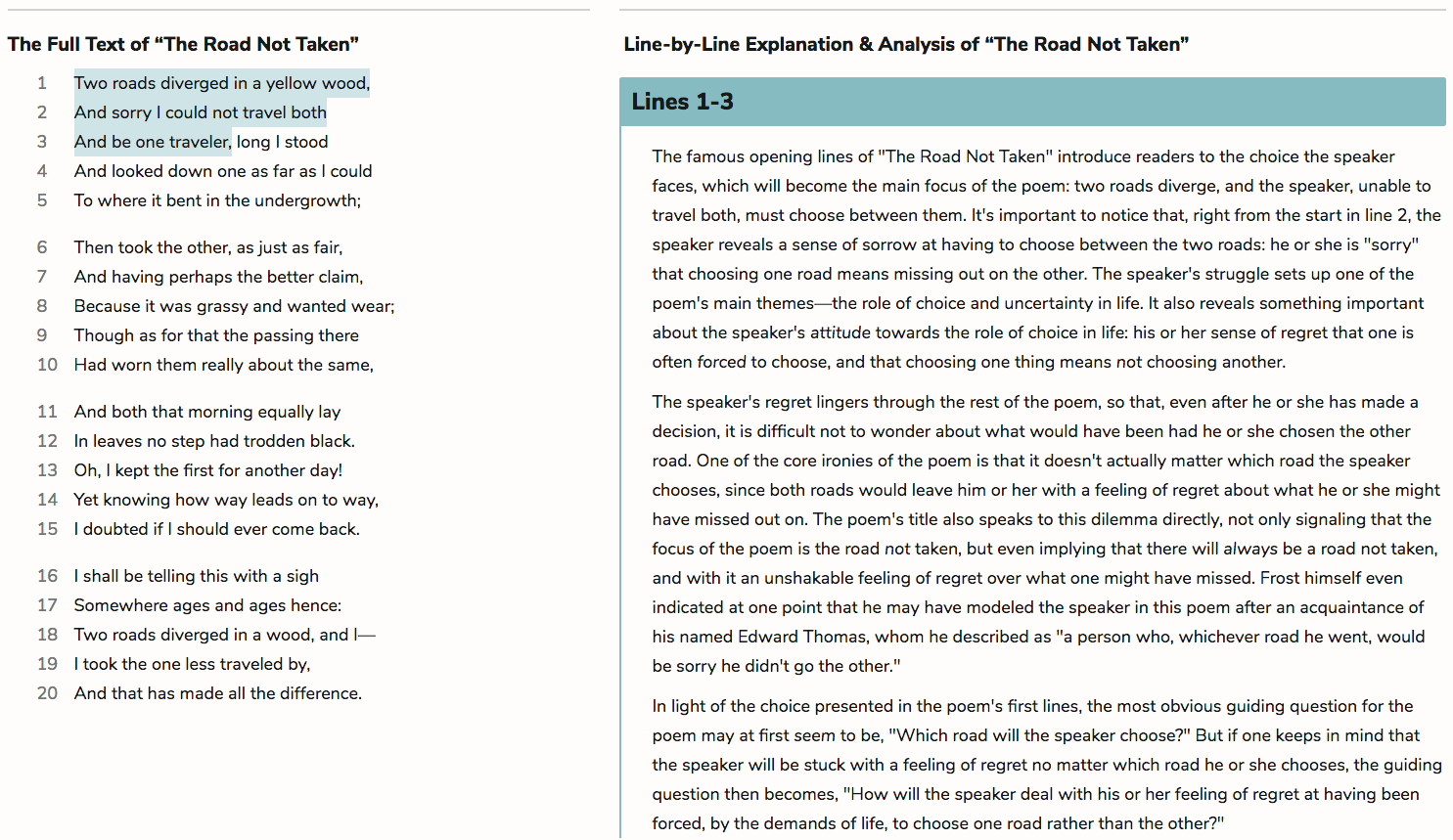

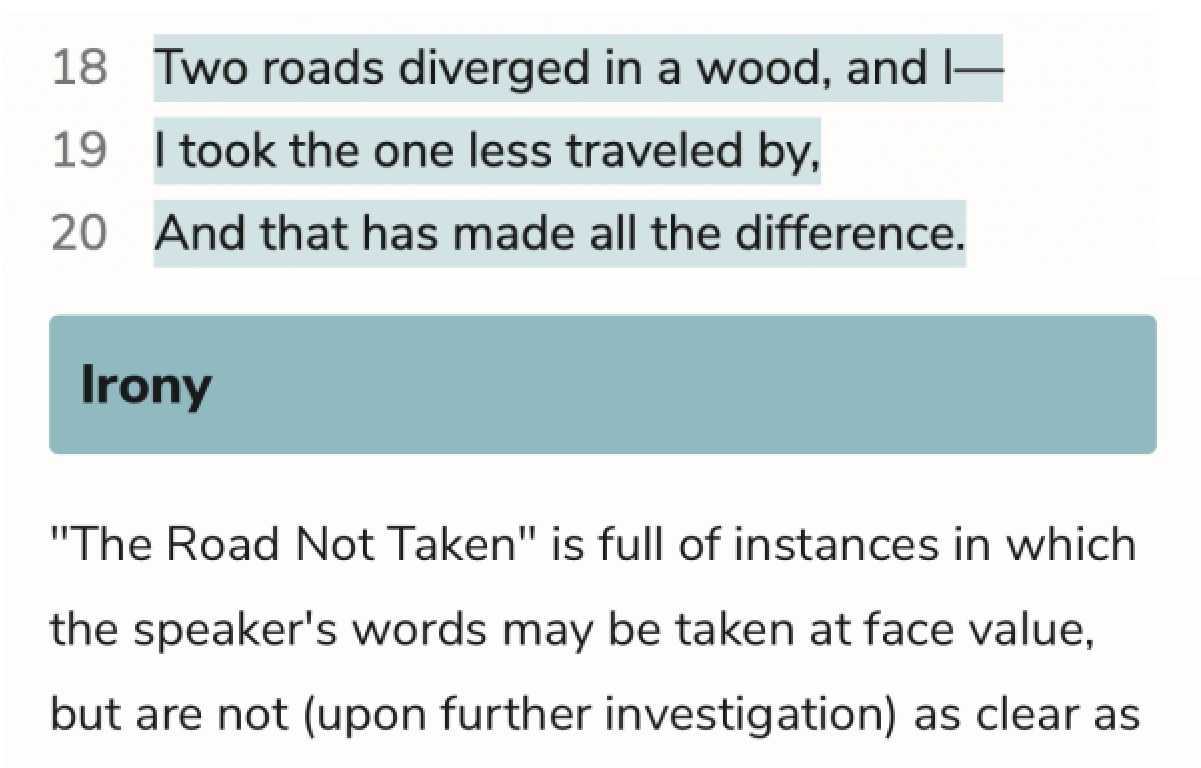

Line-by-line explanations and analysis of figurative language and poetic devices.

For every lyric poem we cover.

For every lyric poem we cover.