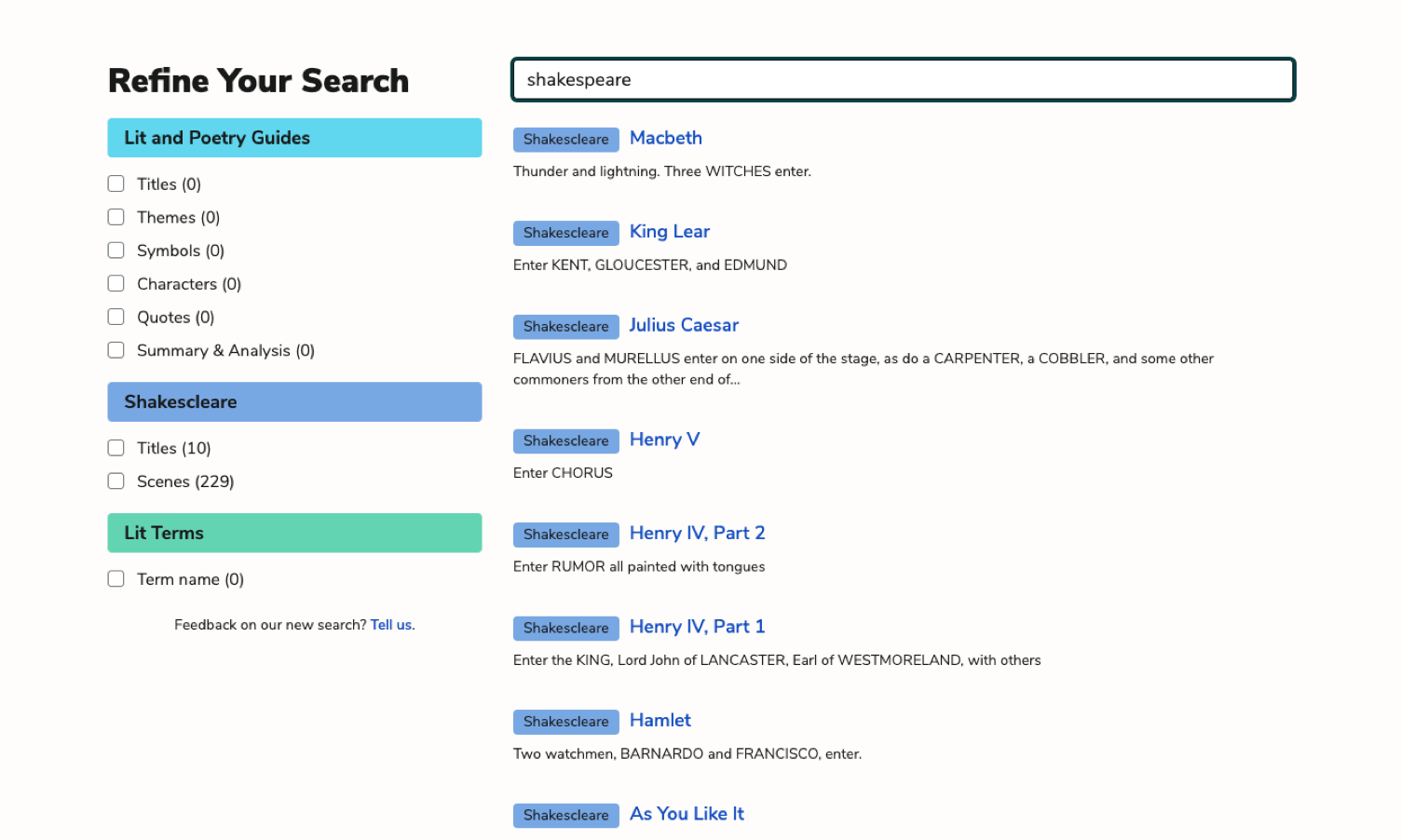

- All's Well That Ends Well

- Antony and Cleopatra

- As You Like It

- The Comedy of Errors

- Coriolanus

- Cymbeline

- Hamlet

- Henry IV, Part 1

- Henry IV, Part 2

- Henry V

- Henry VI, Part 1

- Henry VI, Part 2

- Henry VI, Part 3

- Henry VIII

- Julius Caesar

- King John

- King Lear

- Love's Labor's Lost

- A Lover's Complaint

- Macbeth

- Measure for Measure

- The Merchant of Venice

- The Merry Wives of Windsor

- A Midsummer Night's Dream

- Much Ado About Nothing

- Othello

- Pericles

- The Rape of Lucrece

- Richard II

- Richard III

- Romeo and Juliet

- Shakespeare's Sonnets

- The Taming of the Shrew

- The Tempest

- Timon of Athens

- Titus Andronicus

- Troilus and Cressida

- Twelfth Night

- The Two Gentlemen of Verona

- Venus and Adonis

- The Winter's Tale

plus so much more...

-

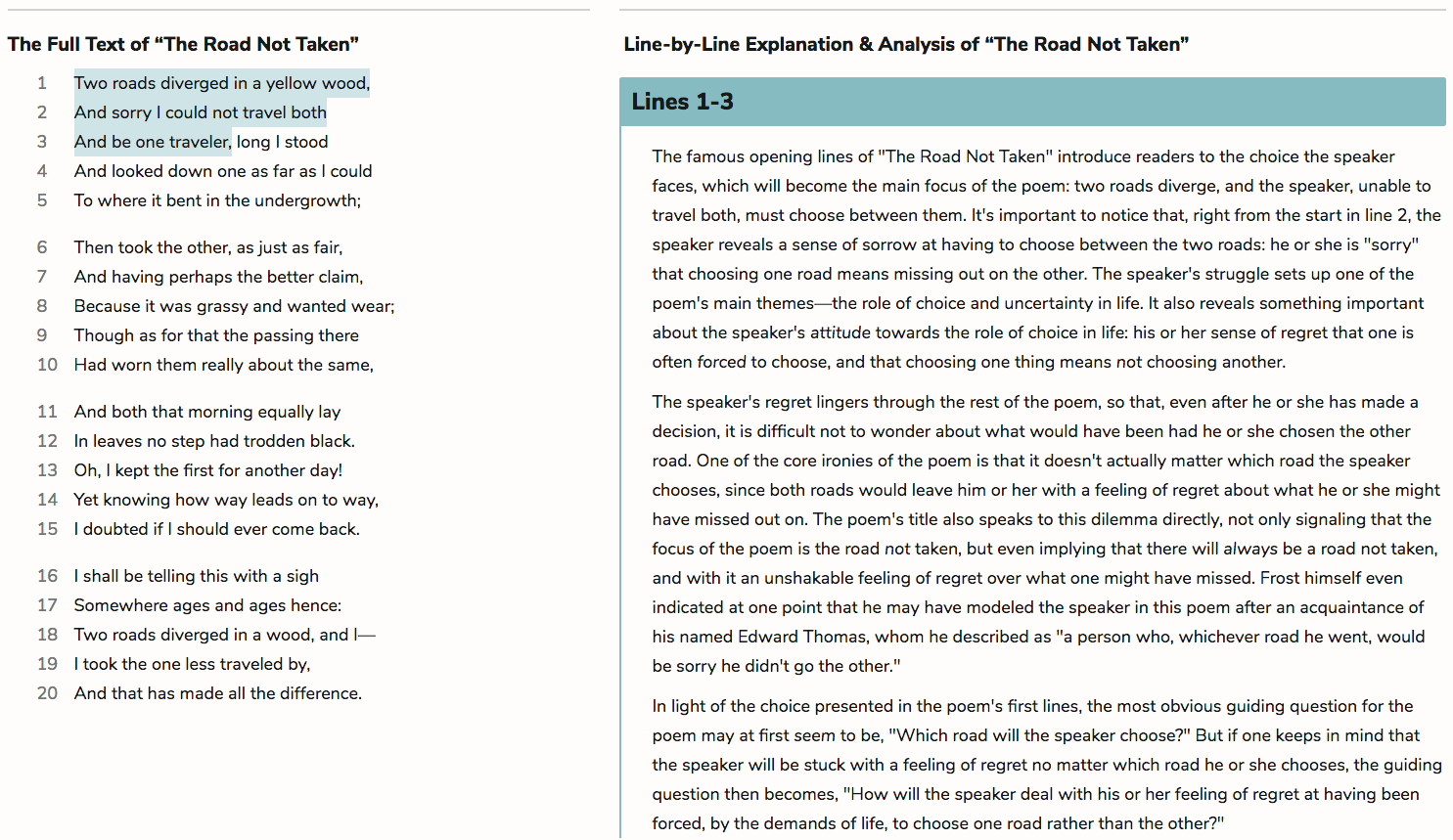

Lines 1-4

The brook, the speaker of the poem, explains its origins in the first line of the poem, claiming to have “come from haunts of coot and hern,” meaning ponds or marshes frequented by coot and heron (two kinds of coastal and freshwater birds). This description of a location both gives the brook a starting point from which it can begin its journey, and is significant because it foregrounds nature—the “coot and hern,” along with their “haunts,” meaning their natural habitats. In this way, the first line hints at the brook’s attitude toward nature versus humankind; it is altogether focused on the natural world around it (of which it is also a part), and sees nature as powerful, important, and enduring. (Humans, in contrast, are just insignificant and temporary visitors—something the brook will explicitly spell out later.)

In the second line, the brook begins its journey with a big rush of energy. The word “sally” suggests that the brook surges forward enthusiastically, but the word can also have a militaristic meaning, suggesting that the brook is making a sudden raid or assault. While the brook isn’t exactly harsh and combative throughout the poem, the martial language emphasizes that the brook is nonetheless a powerful force to be reckoned with. This ties in with the broader idea that nature is powerful and enduring.

The brook is energetic and lively throughout the bulk of the poem. For instance, the word “sparkle” in the third line gives the brook a certain playfulness, and implies that sunlight is reflecting off of the water’s surface. In the fourth line, the word "bicker" means that the brook is making a pleasant trickling sound as it flows into the valley; however, the other, and perhaps more common, meaning of the word bicker—to squabble or argue—subtly gives the brook a more human quality, setting the brook up to be an extended metaphor for human life. In this part of that journey, with its quickness and energy, the brook is like a young child.

The first stanza showcases the structure and meter that persists for the rest of the poem. As a ballad, "The Brook" is broken up into stanzas of four lines, which breaks the poem up into more digestible chunks. The lines are written in common meter—a commonly used meter that alternates between lines of iambic tetrameter and iambic trimeter, or four metric feet per line and three metric feet per line, each with an unstressed-stressed pattern of syllables. However, as the first stanza shows, Tennyson put a little twist on common meter:

I come from haunts of coot and hern:

I make a sudden sally

And sparkle out among the fern,

To bicker down a valley.Note how the second and fourth lines of the poem diverge slightly from common meter by ending in an extra unstressed syllable. In other words, the second and fourth lines of the poem are written in iambic trimeter, or three metric feet of unstressed-stressed syllables—with an extra unstressed syllable floating at the end. This is called a feminine ending, and is actually quite common in poetry. The purpose of feminine endings in "The Brook" is manifold. For now, notice how the feminine endings actually draw attention to the masculine (stressed) endings of the first and third lines: "hern" and "fern." In giving these words special emphasis, the poem emphasizes the importance of the "hern" and "fern" themselves, as elements of nature. In other words, the feminine endings in this stanza actually underscore the poem's broader claim that nature's power and importance is unparalleled.

|

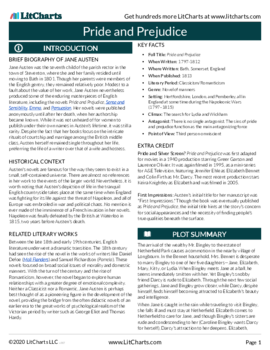

PDF downloads of all 3061 of our lit guides, poetry guides, Shakescleare translations, and literary terms.

PDF downloads of all 1916 LitCharts literature guides, and of every new one we publish.

Learn more

|

|

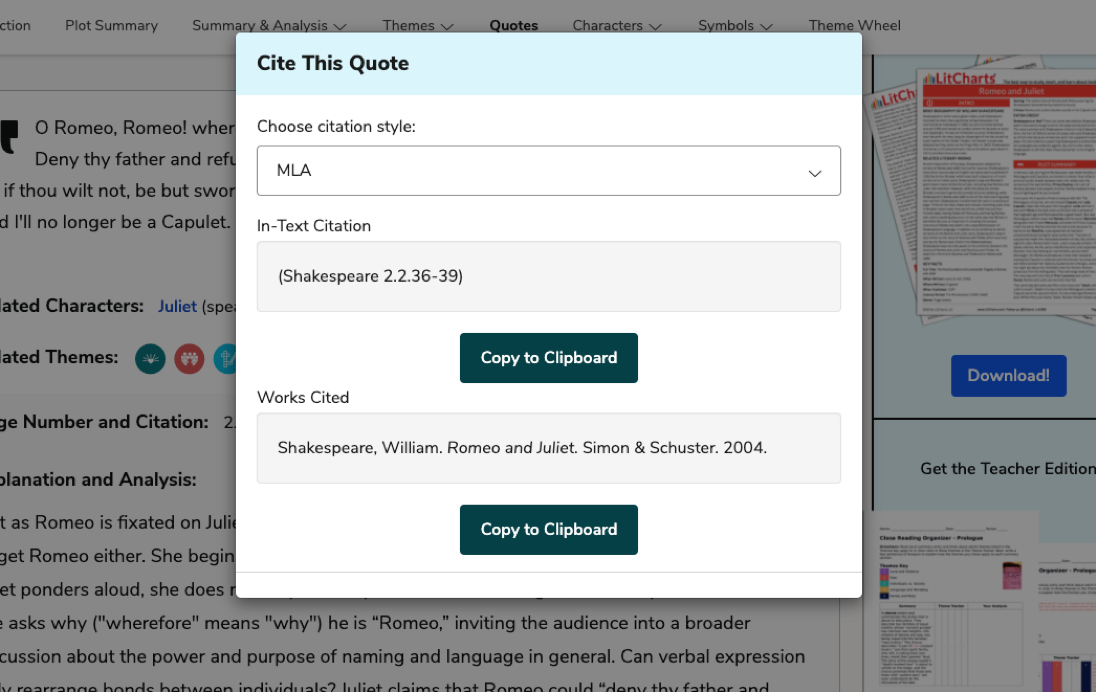

Explanations for every quote we cover.

Detailed quotes explanations (and citation info) for every important quote on the site.

Learn more

|

|

Instant PDF downloads of 136 literary devices and terms.

Definitions and examples for 136 literary devices and terms. Instant PDF downloads.

Learn more

|

|

Compare and contrast related themes.

Compare and contrast Related Themes across different books.

Learn more

|

|

Teacher Editions for all 1916 titles we cover.

LitCharts Teacher Editions for every title we cover.

Learn more

|

|

PDFs of modern translations of every Shakespeare play and poem.

PDFs of modern translations of every Shakespeare play and poem.

Learn more

|

|

Advanced search across our collection.

Advanced Search. Find themes, quotes, symbols, and characters across our collection.

Learn more

|

|

Line-by-line explanations, plus analysis of poetic devices for lyric poems we cover.

Line-by-line explanations, plus analysis of poetic devices for every lyric poem we cover.

Learn more

|

For every lyric poem we cover.

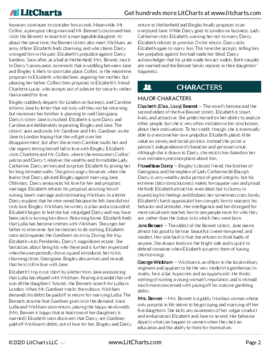

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Quotes Explanations

For all 42,382 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.