plus so much more...

-

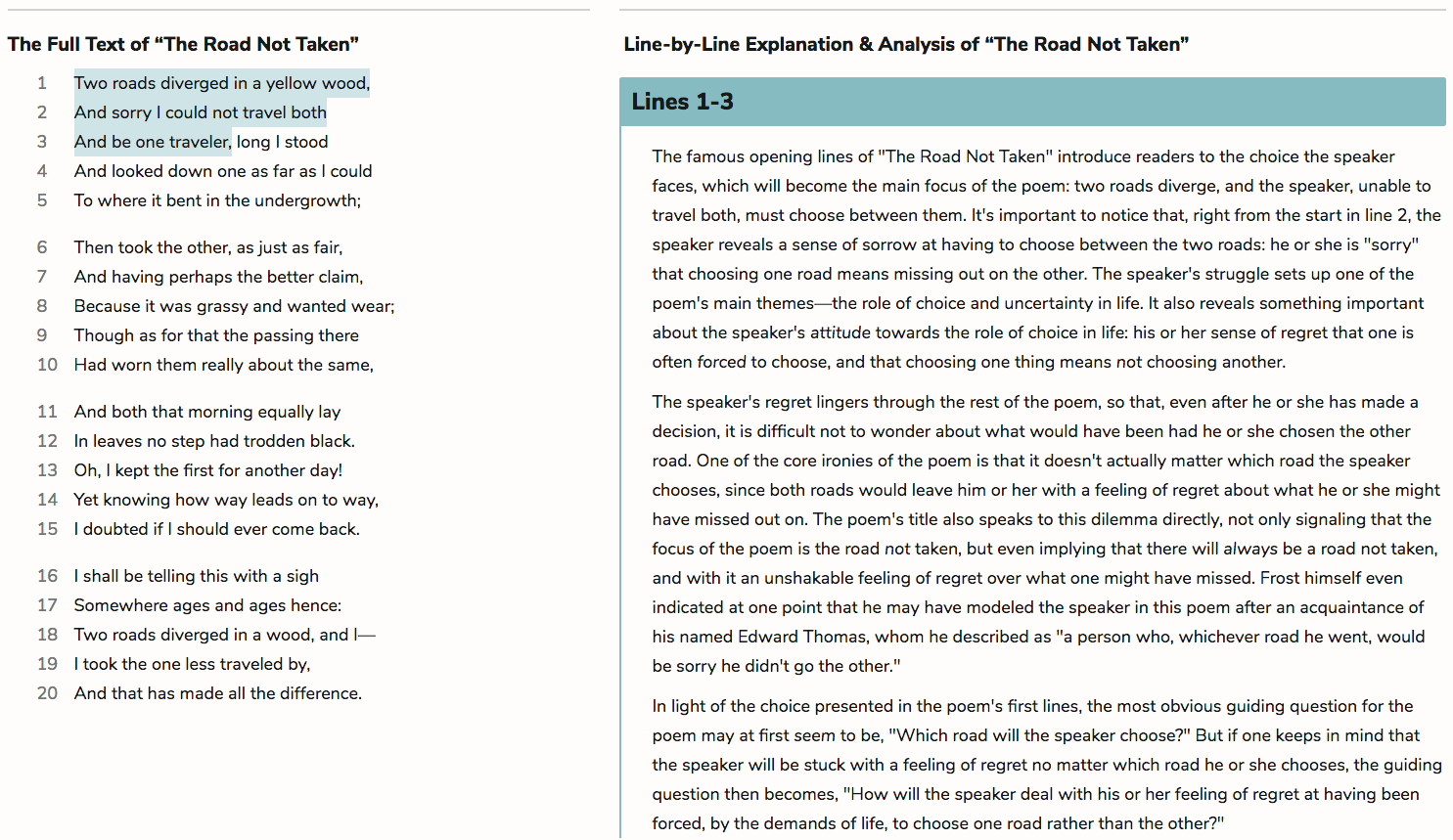

Lines 1-2

The first two lines introduce the poem’s problem, characters, and central confusion—namely, that the world contains the city and nature, but doesn’t seem to actually have room for both.

As an Italian sonnet, the poem's form dictates that it begin with a problem, or “proposition,” and it does so pretty clearly in its opening statement: “The world is too much with us.” (This is also used as its title, though it should be noted that the poem was first published without a title at all). This problem, however, doesn’t have an obvious meaning when considered on its own.

First of all, “world” could refer to the natural world, some world in the imagination, a world created by human beings, or Earth as a whole. “Too much” also garners multiple readings. Is the world just simply “too much,” unbearable and overfull with this many people? Or are those people carrying around the burdens of the world too often, too much of the time?

The ambiguity is a deliberate effort by the poem to blur the line between nature and civilization. This world, and its ambiguities, are too much with us, meaning humans, the ones who must suffer the effects of society’s growth and puzzle over its consequences. Even though the poem speaks for a collective “we,” and continues to do so for the rest of the octave, the end of line 1 and all of line 2 present a very individual perspective (though it is collective in the sense that it’s something nearly all individuals experience). The poem sums up human activity in this manmade world efficiently: humans are always late, soon, getting, and spending. Though abstract, these words have the power to recall vivid memories of waiting in lines, rushing to appointments, earning money for hard work and almost immediately giving it away. These words serve a metonymic function, then, as they represent all forms of economic activity by association.

The content of these lines is reflected in their meter and punctuation. The poem is written in iambic pentameter (five stressed and five unstressed syllables in an alternating pattern), though there is a fair amount of variation:

The world | is too | much with | us; late | and soon,

Getting | and spend- | ing, we | lay waste | our powers;—Note how the arguable stress on "much" leads to two stresses in a row; line 1 has too many stressed syllables in fact (six rather than five), sonically reflecting this "muchness." Line 2 is even more irregular, following a "DUM da da DUM da da" rhythm up top that seems to reflect a sense the tedium or monotony of "getting and spending," only to be abruptly stopped short by the double stress of "lay waste." The sudden spondee here (a foot consisting of two stressed syllables in a row) cuts this waltzing list short, a sharp reminder of the havoc such "getting and spending" is wreaking on people's lives.

The caesuras and end-stops in these lines heighten the frantic tone. A semicolon abruptly ends the opening statement, and at the end of line two, the clunky combination of a semicolon with an em-dash reflects the hindrances that city life imposes on humans. It might, by drawing attention to the punctuation, a tool invented by humans to better convey language, highlight the artificial nature of living in a city.

With its final clause, “we lay waste our powers,” line 2 hints at one of the poem’s central questions. Later on, the speaker will implicitly wonder whether there’s any chance humans can regain their “powers” and reconnect with nature. “Lay waste” describes the utter destruction of those powers. So, before the poem has fully expressed the problem, it offers an opinion about whether it can be solved.

|

PDF downloads of all 3129 of our lit guides, poetry guides, Shakescleare translations, and literary terms.

PDF downloads of all 1970 LitCharts literature guides, and of every new one we publish.

Learn more

|

|

Explanations for every quote we cover.

Detailed quotes explanations (and citation info) for every important quote on the site.

Learn more

|

|

Instant PDF downloads of 136 literary devices and terms.

Definitions and examples for 136 literary devices and terms. Instant PDF downloads.

Learn more

|

|

Compare and contrast related themes.

Compare and contrast Related Themes across different books.

Learn more

|

|

Teacher Editions for all 1970 titles we cover.

LitCharts Teacher Editions for every title we cover.

Learn more

|

|

PDFs of modern translations of every Shakespeare play and poem.

PDFs of modern translations of every Shakespeare play and poem.

Learn more

|

|

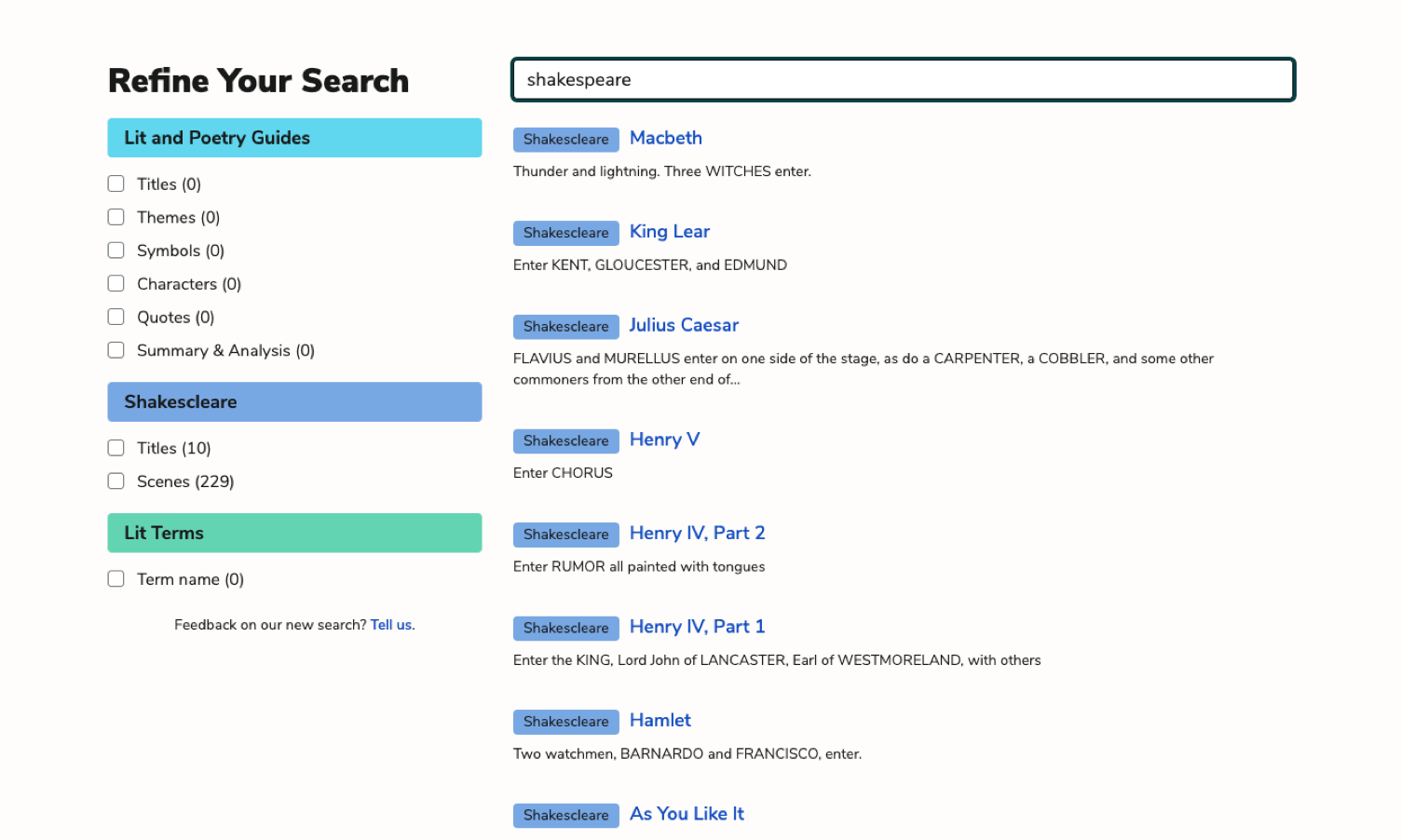

Advanced search across our collection.

Advanced Search. Find themes, quotes, symbols, and characters across our collection.

Learn more

|

|

Line-by-line explanations, plus analysis of poetic devices for lyric poems we cover.

Line-by-line explanations, plus analysis of poetic devices for every lyric poem we cover.

Learn more

|

For every lyric poem we cover.

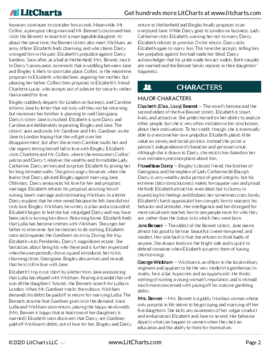

Literature Guide PDFs

LitCharts PDFs for every book you'll read this year.

Quotes Explanations

For all 43,545 quotes we cover.

Teacher Editions

Time saved for teachers.

For every book we cover.

Common Core-aligned

PDFs of modern translations of every one of Shakespeare's 37 plays, 154 sonnets, and 3 longer poems.

Plus a quick-reference PDF with concise definitions of all 136 terms in one place.